guide:66c44a0b4c: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="d-none"><math> | |||

\newcommand{\ex}[1]{\item } | |||

\newcommand{\sx}{\item} | |||

\newcommand{\x}{\sx} | |||

\newcommand{\sxlab}[1]{} | |||

\newcommand{\xlab}{\sxlab} | |||

\newcommand{\prov}[1] {\quad #1} | |||

\newcommand{\provx}[1] {\quad \mbox{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\intext}[1]{\quad \mbox{#1} \quad} | |||

\newcommand{\R}{\mathrm{\bf R}} | |||

\newcommand{\Q}{\mathrm{\bf Q}} | |||

\newcommand{\Z}{\mathrm{\bf Z}} | |||

\newcommand{\C}{\mathrm{\bf C}} | |||

\newcommand{\dt}{\textbf} | |||

\newcommand{\goesto}{\rightarrow} | |||

\newcommand{\ddxof}[1]{\frac{d #1}{d x}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddx}{\frac{d}{dx}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddt}{\frac{d}{dt}} | |||

\newcommand{\dydx}{\ddxof y} | |||

\newcommand{\nxder}[3]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{d{#3}^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\deriv}[2]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{dx^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\dist}{\mathrm{distance}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccot}{\mathrm{arccot\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccsc}{\mathrm{arccsc\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsec}{\mathrm{arcsec\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arctanh}{\mathrm{arctanh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsinh}{\mathrm{arcsinh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccosh}{\mathrm{arccosh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\sech}{\mathrm{sech\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\csch}{\mathrm{csch\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\conj}[1]{\overline{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb} | |||

</math></div> | |||

==<span id="sec 8.1"></span>Average Value of a Function.== | |||

Let <math>f</math> be a real-valued function of a real variable which is bounded on the closed interval <math>[a, b]</math>. Furthermore, let <math>f</math> be integrable over <math>[a, b]</math>. Then the '''mean''', or '''average value''', of <math>f</math> on the interval <math>[a, b]</math> will be denoted by <math>M_a^b(f)</math> and is defined by | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

M_a^b(f) = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} | |||

\frac{1}{b - a} \int_a^b f, &\;\;\; \mbox{if}\; a < b,\\ | |||

f(a), &\;\;\; \mbox{if}\; a = b. | |||

\end{array} | |||

\right . | |||

</math> | |||

If <math>a < b</math>, then it follows at once from the definition that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

(b - a)M_a^b(f) = \int_a^b f . | |||

</math> | |||

This equation is also true if <math>a = b</math>, for then,both sides are equal to zero. We conclude that | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-1| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_a^b f = (b - a)M_a^b(f). | |||

</math>|}} | |||

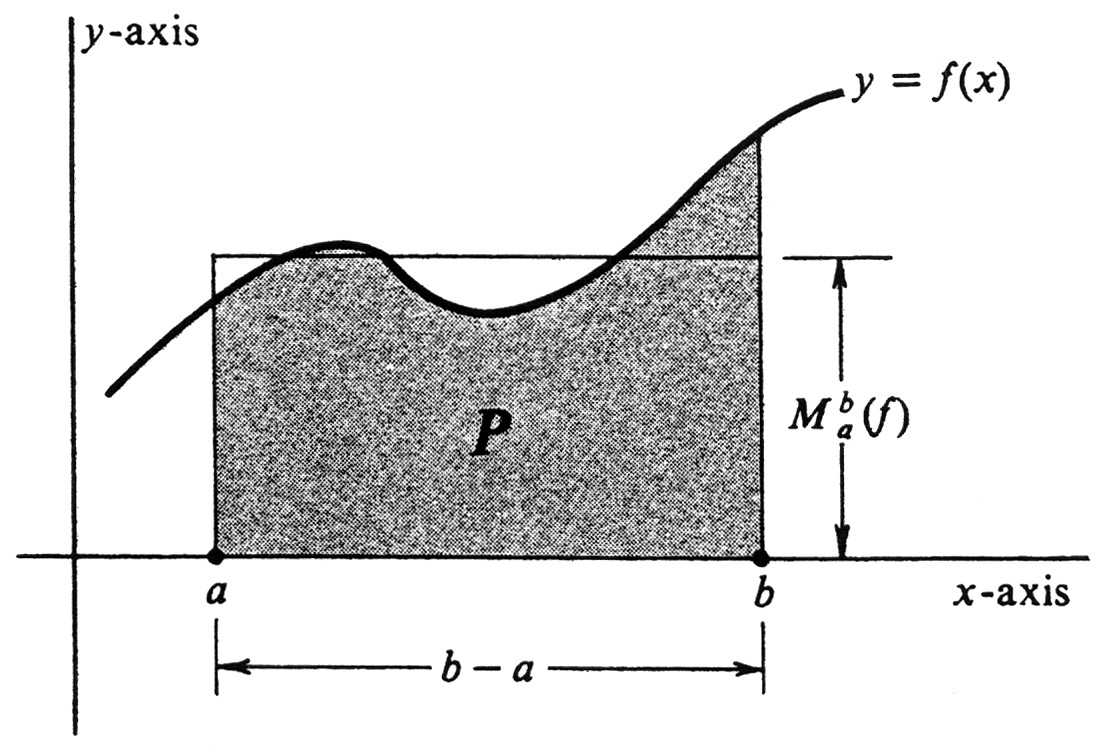

If <math>f</math> is nonnegative on <math>[a, b]</math>, i.e., if <math>f(x) \geq 0</math> for every <math>x</math> such that <math>a \leq x \leq b</math>, then (1.1) yields a good geometric interpretation of the mean <math>M_a^b(f)</math>. Let <math>P</math> be the set of all points <math>(x,y)</math> such that <math>a \leq x \leq b</math> and <math>0 \leq y \leq f(x)</math>, as shown in Figure 1. Then | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

area(P) = \int_a^b f = (b - a)M_a^b(f). | |||

</math> | |||

It follows that <math>M_a^b(f)</math> is equal to the height of a rectangle with the same base and the same area as <math>P</math>. | |||

<div id="fig 8.1" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig8_1.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

<span id="fig 8.2"/> | |||

'''Example''' | |||

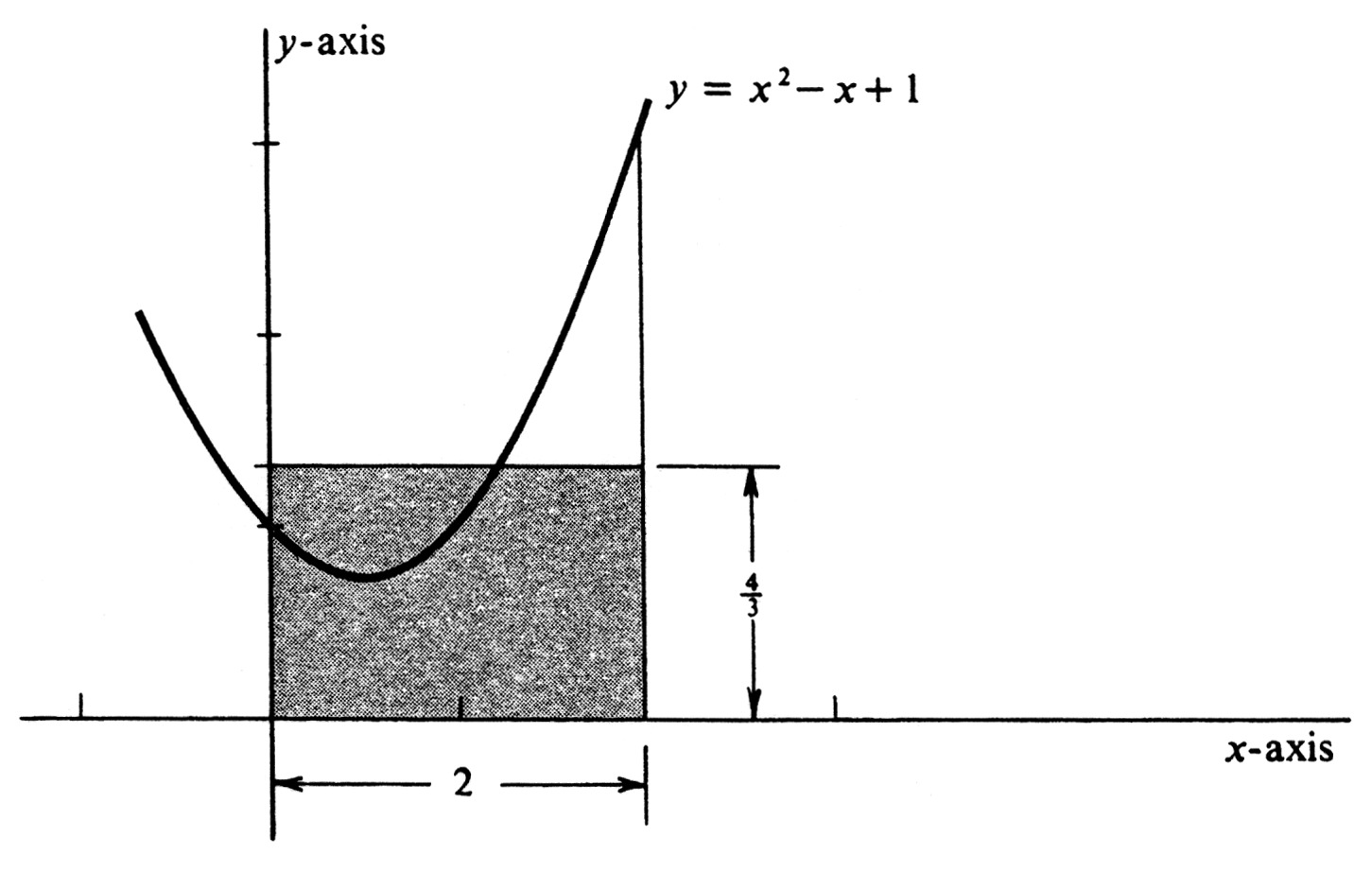

Let <math>f</math> be the function defined by <math>f(x) = x^2 - x + 1</math>. Find the average value of <math>f</math> on the interval <math>[0, 2]</math>, draw the graph of <math>f</math>, and show on it the rectangle with base <math>[0, 2]</math> and area equal to the area under the curve. The graph is shown in Figure 2. The mean, or average value, of <math>f</math> is given by | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

M_0^2( f ) &=& \frac{1}{2 - 0} \int_0^2 f (x) dx\\ | |||

&=& \frac{1}{2} \int_0^2 (x^2 - x + 1)dx \\ | |||

&=& \frac{1}{2}(\frac{x^3}{3} - \frac{x^2}{2} + x) \big|_0^2 = \frac{4}{3} . | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

<div id="fig 8.2" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig8_2.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

The words “mean” and “average value” are common in our vocabularies and have intuitive meaning for most of us. To use them as names for <math>M_a^b(f)</math> is a sensible thing to do only if this quantity, as we have defined it, has the properties we associate with these words. We shall now show that it does. | |||

First, let us verify that the average value of a velocity function agrees with our earlier definition of average velocity. We consider a particle moving along a straight line, which we take to be a coordinate axis. The position and instantaneous velocity of the particle at time <math>t</math> are denoted by <math>s(t)</math> and <math>v(t)</math>, respectively, and we know that <math>s'(t) = v(t)</math>. Suppose that the interval of motion is from time <math>t = a</math> to time <math>t = b</math> and that <math>a < b</math>. Assuming that <math>v</math> is a continuous function, we have | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_a^b v(t) dt = s(b) - s(a). | |||

</math> | |||

According to the definition on page 104, the average velocity <math>v_{av}</math> is equal to | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

v_{av} = \frac{s(b) - s(a)}{b - a} . | |||

</math> | |||

The mean, or average value, of the function <math>v</math> on the interval <math>[a, b]</math> is given by | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

M_a^b(v) &=& \frac{1}{b-a} \int_a^b v(t) dt\\ | |||

&=& \frac{s(b) - s(a)}{b-a} = v_{av}. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

Hence the two definitions agree. | |||

The basic properties of the average value of a function correspond closely to the basic properties of the definite integral as they are enumerated at the beginning of Section 4 of Chapter 4. To begin with, we would expect a function which is constant on an interval to have, on that interval, an average value equal to the constant value of the function. The following proposition states that this is so. | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-2|If <math>f(x) = k</math> for every <math>x</math> in the interval <math>[a, b]</math>, then <math>M_a^b (f) = k</math>.|}} | |||

The proof is an immediate corollary of the definition of the mean <math>M_a^b (f)</math> and of Theorem (4.1), page 191. The reader should supply the details. | |||

If one function is less than or equal to another function on some interval, then the lesser one should have the smaller average value. Thus we expect the theorem: | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-3|If <math>f</math> and <math>g</math> are integrable over <math>[a, b]</math> and if <math>f (x) \leq g(x)</math> for every <math>x</math> in <math>[a, b]</math>, then <math>M_a^b (f) \leq M_a^b (g)</math>.|}} | |||

The proof follows easily from Theorem (4.3), page 191. | |||

We introduce the third property of the average value of a function by means of an example. Suppose that on a 5-hour automobile trip the average velocity is 45 miles per hour during the first 3 hours and 30 during the last 2 hours. What is the average velocity for the whole trip? To get the answer, we observe that the total distance traveled is | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

45 \cdot 3 + 30 \cdot 2 = 195 \;\mbox{miles.} | |||

</math> | |||

The average velocity over 5 hours is, therefore, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\frac{195}{5} = 39 \;\mbox{mph.} | |||

</math> | |||

If we denote the instantaneous velocity of the automobile by <math>v(t)</math>, and assume that the trip began at time <math>t = 0</math>, then we can express the fact that the average velocity over the first 3 hours was 45 miles per hour by the equation <math>M_0^3(v) = 45</math>. Similarly, we are given <math>M_3^5(v) = 30</math> and have shown that <math>M_0^5(v) = 39</math>. Since <math>3 \cdot 45 + 2 \cdot 30 = 5 \cdot 39</math>, we can write | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

(3 - 0)M_0^3(v) + (5 - 3)M_3^5(v) = (5 - 0)M_0^5(v). | |||

</math> | |||

Abstracting from this example, we conclude that the average value of a function should have the property expressed in the proposition: | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-4|If <math>f</math> is integrable over <math>[a, b]</math> and <math>[b, c]</math>, then | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

(b - a)M_a^{b}(f) + (c - b)M_b^{c}(f) = (c - a)M_a^{c}(f). | |||

</math> | |||

|Since <math>(b - a)M_a^b(f) = \int_a^b f</math>, the conclusion of (1.4) is equivalent to the equation | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_a^b f + \int_b^c f = \int_a^c f . | |||

</math> | |||

But this is one of the basic properties of the definite integral [see Theorem (4.2), page 191], so the proof is complete.}} | |||

The next theorem states the properties of the mean corresponding to Theorems (4.4) and (4.5), page 191. | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-5|If <math>f</math> and <math>g</math> are integrable over <math>[a, b]</math> and if <math>k</math> is any real number, then | |||

\item[i]] <math>M_a^b(kf)= kM_a^b(f),</math> | |||

\item[(ii)] <math>M_a^b(f + g) = M_a^b(f ) + M_a^b(g).</math> | |||

The proofs are left as exercises.|}} | |||

<span id="fig 8.3"/> | |||

'''Example''' | |||

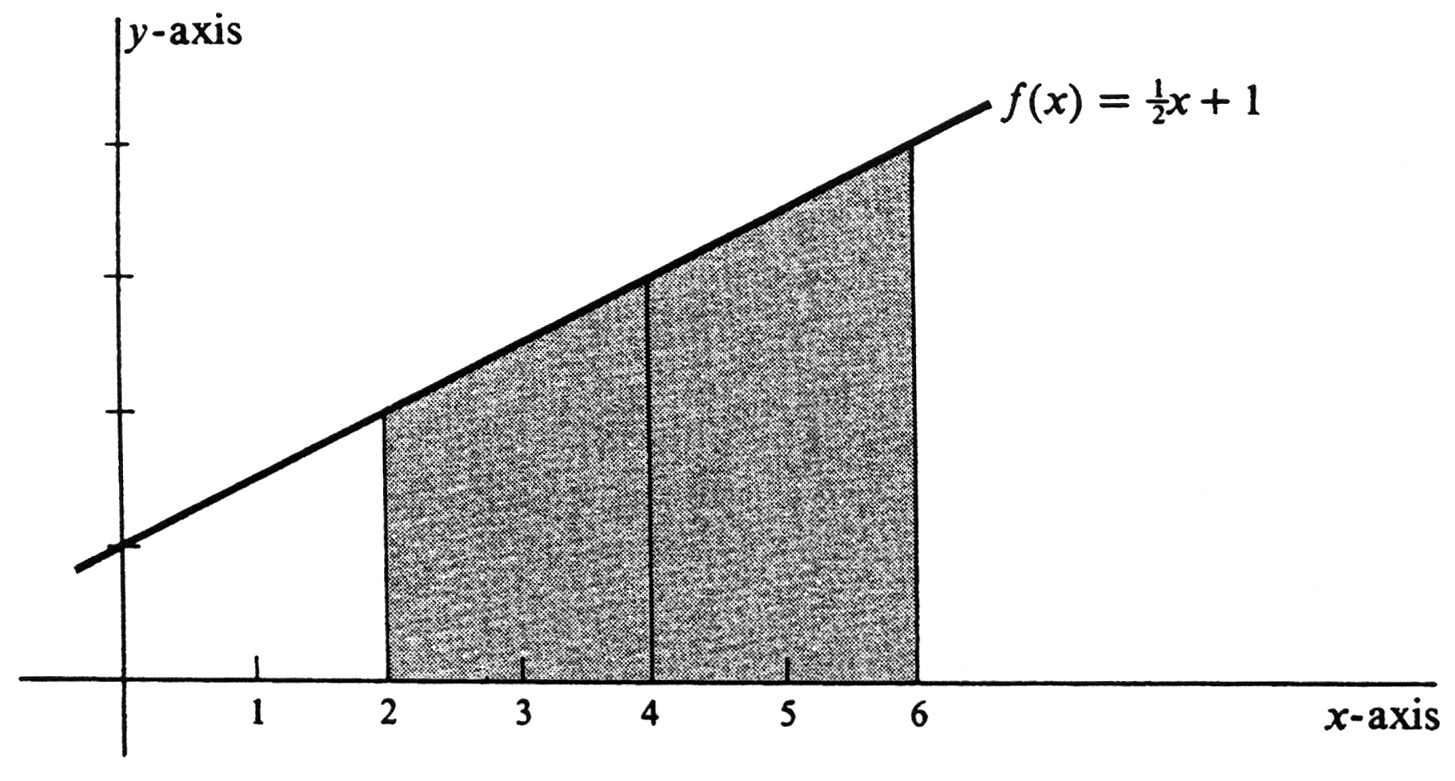

Let us see whether the definition of average value of a function agrees with our intuition in a simple example. Let <math>f</math> be the linear function defined by | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f(x) = \frac{1}{2} x + 1, | |||

</math> | |||

whose graph is shown in Figure 3. What is the average value of <math>f</math> between | |||

2 and 6? | |||

<div id="fig 8.3" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig8_3.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

We have <math>f(2) = \frac{1}{2} \cdot 2 + 1 = 2</math> and <math>f(6) = \frac{1}{2} \cdot 6 + 1 = 4</math>. Since the graph of <math>f</math> is a straight line, the region below the curve is a trapezoid. It would seem natural for the average value of <math>f</math> on the interval to be the length of the median, which is given by | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\frac{f(2) + f(6)}{2} = \frac{2 + 4}{2} = 3. | |||

</math> | |||

Computation of <math>M_2^6(f)</math> yields | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

M_2^6(f) &=& \frac{1}{6 - 2} \int_2^6 (\frac{1}{2}x + 1)dx \\ | |||

&=& \frac{1}{4} (\frac{x^2}{4} + x)\Big|_2^6 \\ | |||

&=& \frac{1}{4} [( \frac{36}{4} + 6) - (\frac{4}{4} + 2)] \\ | |||

&=& \frac{1}{4} (15 - 3) = 3. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

In motivating the definition of the mean, or average value, of a function, we have seen its very close connection with the definite integral. Since a beginning student of calculus probably has a greater feeling for the idea of average than for that of an integral, it is fruitful to reverse our point of view. | |||

That is, if we were to ask the question “What really is the definite integral of a function?”, one answer is that it is a weighted average. Specifically, as stated in (1.1), the integral <math>\int_a^bf</math> is equal to the product of <math>b - a</math> and the average value of <math>f</math> on the interval <math>[a, b]</math>. | |||

We conclude this section with a theorem which is sometimes called the integral form of the Mean Value Theorem. It asserts that if <math>f</math> is continuous, the number <math>M_a^b(f)</math>, which we have called an average value, is quite literally the value of the function <math>f</math> for some number between <math>a</math> and <math>b</math>. | |||

\medskip | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-6|INTEGRAE FORM OF MEAN VALUE THEOREM. | |||

If <math>a < b</math> and if <math>f</math> is continuous on the interval <math>[a, b]</math>, then there exists a number <math>c</math> such that <math>a < c < b</math> and <math>M_a^b(f) = f(c)</math>. | |||

|Since <math>f</math> is continuous at every point of <math>[a, b]</math>, it follows by the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus that the function <math>F</math>, defined by | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

F(x) = \int_a^b f(t) dt, \;\;\;\mbox{for every $x$ in <math>[a, b]</math>,} | |||

</math> | |||

is differentiable. Furthermore, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

F'(x) = f (x), \;\;\;\mbox{for every $x$ in <math>[a, b]</math>.} | |||

</math> | |||

A differentiable function is necessarily continuous [see (6.1), page 55], and so <math>F</math> more than satisfies the hypotheses of the Mean Value Theorem, (5.2), page 113. That theorem therefore implies that there exists a number <math>c</math> such that <math>a < c < b</math> and | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

F(b) - F(a) = (b - a)F'(c). | |||

</math> | |||

But <math>F'(c) = f(c)</math>, and | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

F(b) - F(a) = \int_a^b f(x)dx. | |||

</math> | |||

Hence | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_a^b f (x) dx = (b - a) f(c), | |||

</math> | |||

and so | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f(c) = \frac{1}{b - a} \int_a^b f(x) dx = M_a^b(f). | |||

</math> | |||

This completes the proof.}} | |||

\end{exercise} | |||

==General references== | |||

{{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | |||

Revision as of 01:08, 3 November 2024

Average Value of a Function.

Let [math]f[/math] be a real-valued function of a real variable which is bounded on the closed interval [math][a, b][/math]. Furthermore, let [math]f[/math] be integrable over [math][a, b][/math]. Then the mean, or average value, of [math]f[/math] on the interval [math][a, b][/math] will be denoted by [math]M_a^b(f)[/math] and is defined by

If [math]a \lt b[/math], then it follows at once from the definition that

This equation is also true if [math]a = b[/math], for then,both sides are equal to zero. We conclude that

If [math]f[/math] is nonnegative on [math][a, b][/math], i.e., if [math]f(x) \geq 0[/math] for every [math]x[/math] such that [math]a \leq x \leq b[/math], then (1.1) yields a good geometric interpretation of the mean [math]M_a^b(f)[/math]. Let [math]P[/math] be the set of all points [math](x,y)[/math] such that [math]a \leq x \leq b[/math] and [math]0 \leq y \leq f(x)[/math], as shown in Figure 1. Then

It follows that [math]M_a^b(f)[/math] is equal to the height of a rectangle with the same base and the same area as [math]P[/math].

Example Let [math]f[/math] be the function defined by [math]f(x) = x^2 - x + 1[/math]. Find the average value of [math]f[/math] on the interval [math][0, 2][/math], draw the graph of [math]f[/math], and show on it the rectangle with base [math][0, 2][/math] and area equal to the area under the curve. The graph is shown in Figure 2. The mean, or average value, of [math]f[/math] is given by

The words “mean” and “average value” are common in our vocabularies and have intuitive meaning for most of us. To use them as names for [math]M_a^b(f)[/math] is a sensible thing to do only if this quantity, as we have defined it, has the properties we associate with these words. We shall now show that it does. First, let us verify that the average value of a velocity function agrees with our earlier definition of average velocity. We consider a particle moving along a straight line, which we take to be a coordinate axis. The position and instantaneous velocity of the particle at time [math]t[/math] are denoted by [math]s(t)[/math] and [math]v(t)[/math], respectively, and we know that [math]s'(t) = v(t)[/math]. Suppose that the interval of motion is from time [math]t = a[/math] to time [math]t = b[/math] and that [math]a \lt b[/math]. Assuming that [math]v[/math] is a continuous function, we have

According to the definition on page 104, the average velocity [math]v_{av}[/math] is equal to

The mean, or average value, of the function [math]v[/math] on the interval [math][a, b][/math] is given by

Hence the two definitions agree. The basic properties of the average value of a function correspond closely to the basic properties of the definite integral as they are enumerated at the beginning of Section 4 of Chapter 4. To begin with, we would expect a function which is constant on an interval to have, on that interval, an average value equal to the constant value of the function. The following proposition states that this is so.

If [math]f(x) = k[/math] for every [math]x[/math] in the interval [math][a, b][/math], then [math]M_a^b (f) = k[/math].

The proof is an immediate corollary of the definition of the mean [math]M_a^b (f)[/math] and of Theorem (4.1), page 191. The reader should supply the details. If one function is less than or equal to another function on some interval, then the lesser one should have the smaller average value. Thus we expect the theorem:

If [math]f[/math] and [math]g[/math] are integrable over [math][a, b][/math] and if [math]f (x) \leq g(x)[/math] for every [math]x[/math] in [math][a, b][/math], then [math]M_a^b (f) \leq M_a^b (g)[/math].

The proof follows easily from Theorem (4.3), page 191. We introduce the third property of the average value of a function by means of an example. Suppose that on a 5-hour automobile trip the average velocity is 45 miles per hour during the first 3 hours and 30 during the last 2 hours. What is the average velocity for the whole trip? To get the answer, we observe that the total distance traveled is

The average velocity over 5 hours is, therefore,

If we denote the instantaneous velocity of the automobile by [math]v(t)[/math], and assume that the trip began at time [math]t = 0[/math], then we can express the fact that the average velocity over the first 3 hours was 45 miles per hour by the equation [math]M_0^3(v) = 45[/math]. Similarly, we are given [math]M_3^5(v) = 30[/math] and have shown that [math]M_0^5(v) = 39[/math]. Since [math]3 \cdot 45 + 2 \cdot 30 = 5 \cdot 39[/math], we can write

Abstracting from this example, we conclude that the average value of a function should have the property expressed in the proposition:

If [math]f[/math] is integrable over [math][a, b][/math] and [math][b, c][/math], then

Since [math](b - a)M_a^b(f) = \int_a^b f[/math], the conclusion of (1.4) is equivalent to the equation

The next theorem states the properties of the mean corresponding to Theorems (4.4) and (4.5), page 191.

If [math]f[/math] and [math]g[/math] are integrable over [math][a, b][/math] and if [math]k[/math] is any real number, then

\item[i]] [math]M_a^b(kf)= kM_a^b(f),[/math]

\item[(ii)] [math]M_a^b(f + g) = M_a^b(f ) + M_a^b(g).[/math]

The proofs are left as exercises.

Example

Let us see whether the definition of average value of a function agrees with our intuition in a simple example. Let [math]f[/math] be the linear function defined by

whose graph is shown in Figure 3. What is the average value of [math]f[/math] between 2 and 6?

We have [math]f(2) = \frac{1}{2} \cdot 2 + 1 = 2[/math] and [math]f(6) = \frac{1}{2} \cdot 6 + 1 = 4[/math]. Since the graph of [math]f[/math] is a straight line, the region below the curve is a trapezoid. It would seem natural for the average value of [math]f[/math] on the interval to be the length of the median, which is given by

Computation of [math]M_2^6(f)[/math] yields

In motivating the definition of the mean, or average value, of a function, we have seen its very close connection with the definite integral. Since a beginning student of calculus probably has a greater feeling for the idea of average than for that of an integral, it is fruitful to reverse our point of view.

That is, if we were to ask the question “What really is the definite integral of a function?”, one answer is that it is a weighted average. Specifically, as stated in (1.1), the integral [math]\int_a^bf[/math] is equal to the product of [math]b - a[/math] and the average value of [math]f[/math] on the interval [math][a, b][/math].

We conclude this section with a theorem which is sometimes called the integral form of the Mean Value Theorem. It asserts that if [math]f[/math] is continuous, the number [math]M_a^b(f)[/math], which we have called an average value, is quite literally the value of the function [math]f[/math] for some number between [math]a[/math] and [math]b[/math].

\medskip

INTEGRAE FORM OF MEAN VALUE THEOREM. If [math]a \lt b[/math] and if [math]f[/math] is continuous on the interval [math][a, b][/math], then there exists a number [math]c[/math] such that [math]a \lt c \lt b[/math] and [math]M_a^b(f) = f(c)[/math].

Since [math]f[/math] is continuous at every point of [math][a, b][/math], it follows by the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus that the function [math]F[/math], defined by

\end{exercise}

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.