guide:4fa8e5a0a7: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 66: | Line 66: | ||

We omit the proof. The result sounds perfectly obvious, of course, and it is obvious in the sense that if continuity means what we want it to mean, then (2.4) must be true. To see whether it, in fact, follows logically from our definitions, of course, requires proof. Further insight into the theorem may be found in Problems 21 and 22, where it is shown that functions that do not satisfy the hypotheses of (2.4) can fail to have absolute extreme points. | We omit the proof. The result sounds perfectly obvious, of course, and it is obvious in the sense that if continuity means what we want it to mean, then (2.4) must be true. To see whether it, in fact, follows logically from our definitions, of course, requires proof. Further insight into the theorem may be found in Problems 21 and 22, where it is shown that functions that do not satisfy the hypotheses of (2.4) can fail to have absolute extreme points. | ||

Let us now look at the problems suggested at the beginning of the section. | Let us now look at the problems suggested at the beginning of the section. | ||

<span id="exam 2.2.1"/> | <span id="exam 2.2.1"/> | ||

'''Example''' | '''Example''' | ||

What are the dimensions of the largest rectangular field which can be enclosed with 200 feet of fencing? Should it be long and narrow, short and wide, or somewhere in between? If we let <math>x</math> be the number of feet in the length, then <math>100-x</math> will represent the width, and we can write the area <math>A</math> as a function of <math>x</math>: | What are the dimensions of the largest rectangular field which can be enclosed with 200 feet of fencing? Should it be long and narrow, short and wide, or somewhere in between? If we let <math>x</math> be the number of feet in the length, then <math>100-x</math> will represent the width, and we can write the area <math>A</math> as a function of <math>x</math>: | ||

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

\medskip | \medskip | ||

The problem of solving a maximum or minimum problem consists of setting up the function to be maximized or minimized and then taking derivatives. The theorems of this section tell how to proceed from there. | The problem of solving a maximum or minimum problem consists of setting up the function to be maximized or minimized and then taking derivatives. The theorems of this section tell how to proceed from there. | ||

<span id="exam 2.2.2"/> | <span id="exam 2.2.2"/> | ||

'''Example''' | '''Example''' | ||

What are the dimensions of the cylindrical quart can which can be made from the least amount of tin? This problem is important to the manufacturer who produces tin cans and is more concerned with the amount of tin used than with the shape of the can. Should he make tall cans with a small radius or short cans with a large radius? We shall ignore seams and assume that tin cans are perfect cylinders. The volume of a cylinder is <math>\pi {r^2}h</math> and a quart contains <math>57\frac{3}{4}</math> cubic inches. Thus if <math>r</math> is the radius of the can in inches and <math>h</math> is the height in inches, <math>\pi {r^2}h = 57 \frac{3}{4}</math> or <math>\frac{231}{4}</math>(see [[#fig 2.13|Figure]]). The area is the sum of the lateral surface area and the area of the bottom and the top: <math>A = 2\pi rh + 2\pi {r^2}</math>. The area depends on <math>r</math> and <math>h</math>, but we can use our volume equation to find <math>h</math> as a function of <math>r: h = \frac{231}{4\pi {r^2}}</math>, and then write | What are the dimensions of the cylindrical quart can which can be made from the least amount of tin? This problem is important to the manufacturer who produces tin cans and is more concerned with the amount of tin used than with the shape of the can. Should he make tall cans with a small radius or short cans with a large radius? We shall ignore seams and assume that tin cans are perfect cylinders. The volume of a cylinder is <math>\pi {r^2}h</math> and a quart contains <math>57\frac{3}{4}</math> cubic inches. Thus if <math>r</math> is the radius of the can in inches and <math>h</math> is the height in inches, <math>\pi {r^2}h = 57 \frac{3}{4}</math> or <math>\frac{231}{4}</math>(see [[#fig 2.13|Figure]]). The area is the sum of the lateral surface area and the area of the bottom and the top: <math>A = 2\pi rh + 2\pi {r^2}</math>. The area depends on <math>r</math> and <math>h</math>, but we can use our volume equation to find <math>h</math> as a function of <math>r: h = \frac{231}{4\pi {r^2}}</math>, and then write | ||

<div id="fig 2.13" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | <div id="fig 2.13" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | ||

| Line 120: | Line 120: | ||

'''Example''' | '''Example''' | ||

A telephone company which serves a small community makes an annual profit of \$12 per subscriber if it has 725 subscribers or fewer. They | A telephone company which serves a small community makes an annual profit of \$12 per subscriber if it has 725 subscribers or fewer. They | ||

decide to reduce the rate by a fixed sum for each subscriber over 725, thereby reducing the profit I cent per subscriber. Thus there will be a profit of \$11.99 on each of 726 subscribers, \$11.98 on each of 727, etc. What is the number of subscribers which will give them the greatest profit? | decide to reduce the rate by a fixed sum for each subscriber over 725, thereby reducing the profit I cent per subscriber. Thus there will be a profit of \$11.99 on each of 726 subscribers, \$11.98 on each of 727, etc. What is the number of subscribers which will give them the greatest profit? | ||

| Line 128: | Line 127: | ||

'''Example''' | '''Example''' | ||

Consider the function <math>f</math> defined by | Consider the function <math>f</math> defined by | ||

| Line 171: | Line 169: | ||

Sometimes the geometric or physical properties of the problem make it obvious that a critical point is of the desired type, i.e., a maximum or a minimum. If this happens, it is not necessary to compute the second derivative, although it may still be used as a check. The complete behavior of the function whose extreme points are desired can always be found by carefully plotting its graph. | Sometimes the geometric or physical properties of the problem make it obvious that a critical point is of the desired type, i.e., a maximum or a minimum. If this happens, it is not necessary to compute the second derivative, although it may still be used as a check. The complete behavior of the function whose extreme points are desired can always be found by carefully plotting its graph. | ||

==General references== | ==General references== | ||

{{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | {{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | ||

Revision as of 01:54, 5 November 2024

Maximum and Minimum Problems.

In sketching the graph of a function, we spent some time looking for maximum and minimum points, both local and absolute. This idea suggests that we can use the same technique to find that value (or those values) of a variable which maximize or minimize a length, an area, or a profit. For example, what should be the dimensions of the rectangular field which can be enclosed with a fixed length of fencing but has the greatest area? Or, what are the dimensions of the quart can which can be made from the least amount of tin? Or, if the telephone company were to reduce the rate per instrument for each new instrument over a certain number, what number of telephones would give them the greatest profit? These are all problems which can be solved by calculus and, more specifically, by the technique developed in Section 1. However, before we tackle them, we shall consider the theorems which justify the methods which we shall use in solving them.

If a belongs to an open interval in the domain of [math]f[/math], if [math]f'(a)[/math] exists, and if [math](a, f(a))[/math] is a local extreme point \textrm{(either a maximum or a minimum)}, then [math]f'(a) = 0[/math].

Geometrically this theorem is obvious. We shall prove it, only in the case that [math](a,f(a))[/math] is a local maximum point, since a similar proof (with the inequalities reversed) is valid for a local minimum point. Since [math](a,f(a))[/math] is a local maximum point, [math]f(a + t) \leq f(a)[/math] for all [math]t[/math] in some open interval containing 0. Thus [math]f(a + t)-f(a) \leq 0[/math]. If [math]t[/math] is negative, [math]\frac{f(a+t) - f(a)}{t} \geq 0[/math] and

In our sketches we found points where the first derivative vanished. If the curve was concave downward at that point, we identified a local maximum point; if the curve was concave upward at that point, we identified a local minimum point. We summarize this result in the following theorem.

Let [math]f[/math] be a function with a continuous second derivative and with [math]f'(a) = 0[/math]. Then [math](a, f(a))[/math] is a local maximum point if [math]f''(a) \lt 0[/math] and is a local minimum point if [math]f''(a) \gt 0[/math].

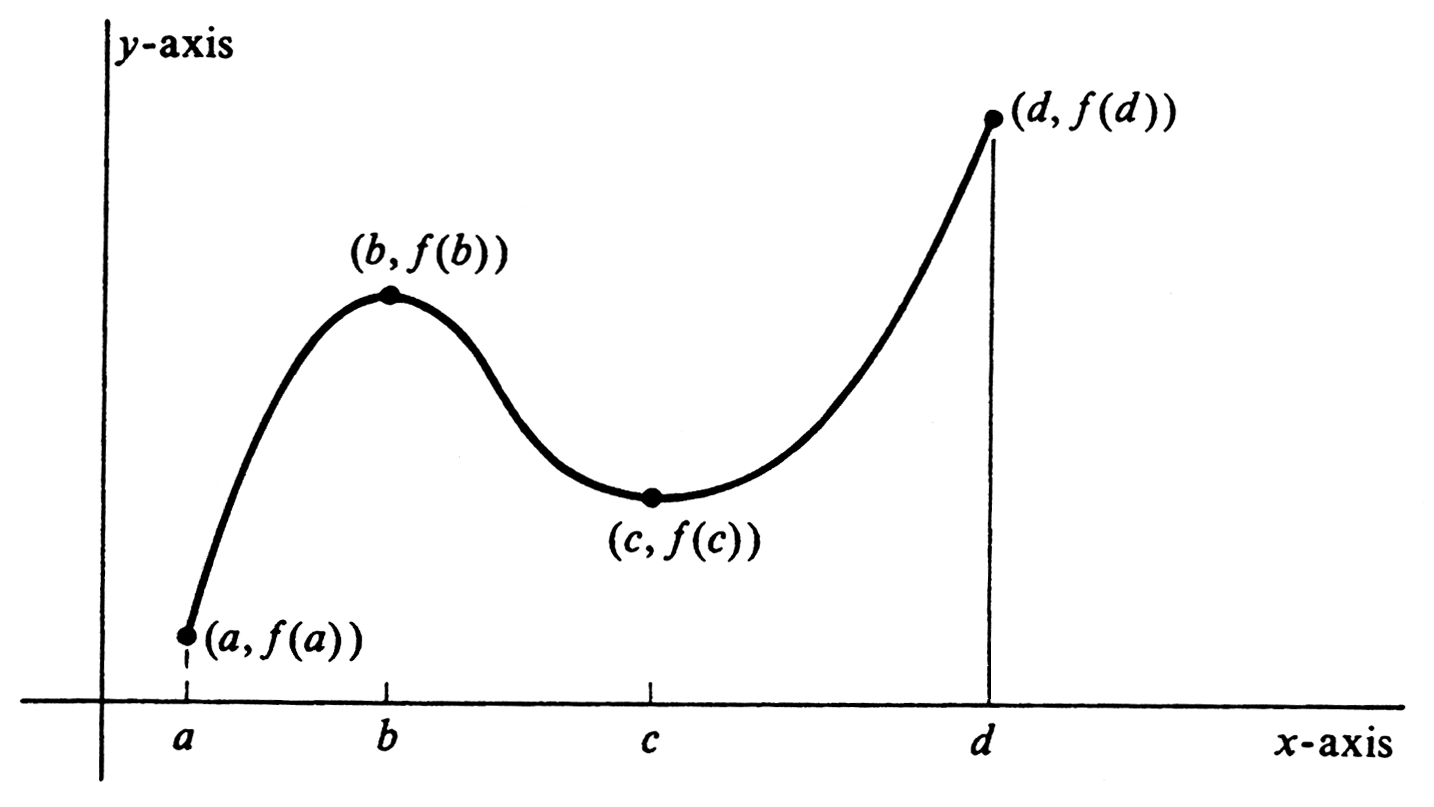

This theorem is easily proved when we have more mathematics at our command. Specifically, it follows quickly from Taylor's Formula with the Remainder (see Problem 13, page 540). For the work at hand, it will be sufficient to understand the theorem and to be able to use it. If the domain of [math]f[/math] is restricted to a closed interval, we may find an absolute extreme point which lies on the boundary of the interval. Consider the function graphed in Figure. This function is defined on the closed interval [math][a, d][/math] and has a local minimum point at[math](c, f(c))[/math]. However, there are several points in [math][a, d][/math] which are lower than [math](c,f(c))[/math], and the absolute minimum point is [math](a, f(a))[/math]. Similarly, [math](b, f(b))[/math] is a local maximum point but [math](d, f(d))[/math] is the absolute maximum point. This suggests the following theorem.

Let [math]f[/math] be a differentiable function whose domain is restricted to a closed interval containing [math]a[/math]. If [math](a, f(a))[/math] is an extreme point then [math]f'(a) = 0[/math] or [math]a[/math] is an endpoint of the interval.

This theorem is an immediate corollary of Theorem (2.1). Let the domain be [math][c, d][/math]. If [math]a \neq c[/math] and [math]a \neq d[/math], then [math]a[/math] lies in the open interval [math](c, d)[/math] and, by Theorem (2.1), [math]f'(a) = 0[/math]. If [math]a = c[/math] or [math]a = d[/math], then [math]a[/math] is an endpoint of the interval.

For many functions, Theorem (2.3) has the virtue of reducing an apparently impossible problem to a simple one. In principle, the problem of finding the maximum values of a function over a closed interval involves the examination of [math]f(x)[/math] for every [math]x[/math] in the interval, i.e., for an infinite number of points. This theorem tells us that we need look only at those values of [math]x[/math] at which the first derivative vanishes and those which are endpoints. For most functions there is only a small finite number of such points. Theorem (2.3) tells us where to look for the extreme points of a differentiable function defined on a closed interval, but it does not guarantee the existence of any. To complete the theory, we add a statement of the following fundamental existence theorem.

Every real-valued continuous function whose domain is a closed bounded interval has at least one absolufe maximum point and at least one absolute minimum point.

We omit the proof. The result sounds perfectly obvious, of course, and it is obvious in the sense that if continuity means what we want it to mean, then (2.4) must be true. To see whether it, in fact, follows logically from our definitions, of course, requires proof. Further insight into the theorem may be found in Problems 21 and 22, where it is shown that functions that do not satisfy the hypotheses of (2.4) can fail to have absolute extreme points. Let us now look at the problems suggested at the beginning of the section.

Example

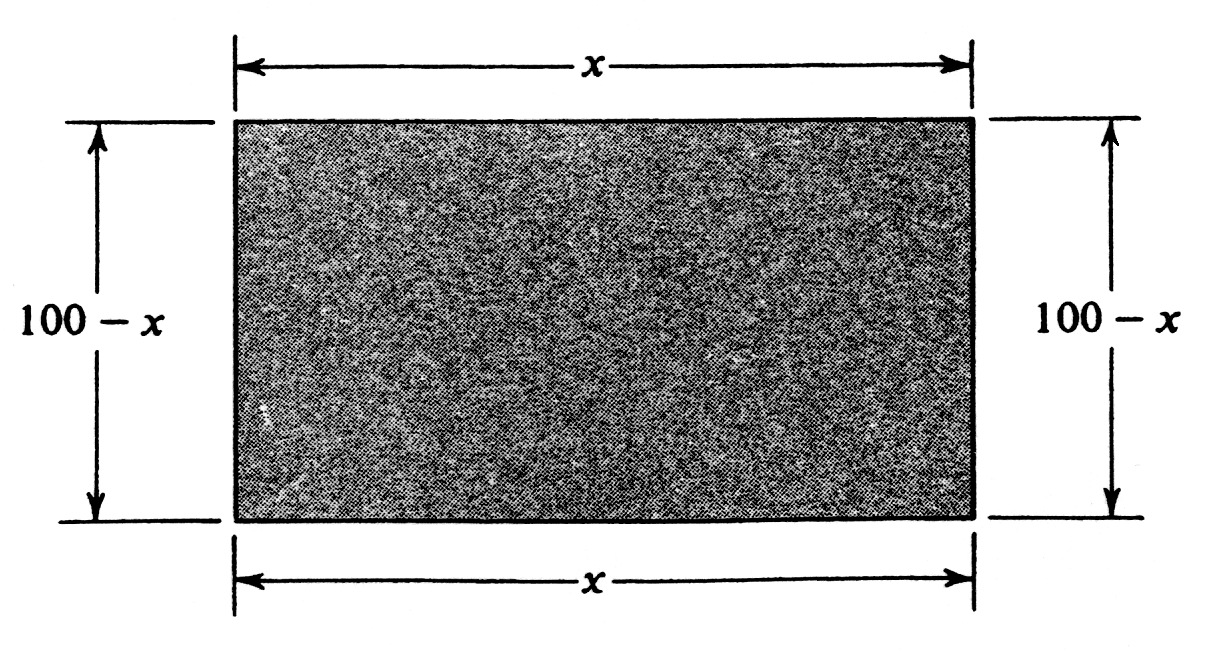

What are the dimensions of the largest rectangular field which can be enclosed with 200 feet of fencing? Should it be long and narrow, short and wide, or somewhere in between? If we let [math]x[/math] be the number of feet in the length, then [math]100-x[/math] will represent the width, and we can write the area [math]A[/math] as a function of [math]x[/math]:

(see Figure). Note that the domain of [math]A[/math] is the interval consisting of all [math]x[/math] such that [math]0 \lt x \lt 100[/math]. We want to find that value of [math]x[/math] which will give a maximum value of [math]A[/math]. Taking derivatives, we obtain [math]A'(x)= 100 - 2x[/math] and [math]A''(x)= -2[/math]. Setting [math]A'[/math] equal to zero, we find [math]x= 50[/math]. Since [math]A'(50) = 0[/math] and [math]A''(50) = -2 \lt 0[/math], we know that 50 is that value of [math]x[/math] which maximizes [math]A[/math]. Thus the field, which is 50 feet long and [math]100 - 50 = 50[/math] feet wide, is the largest rectangular field which can be enclosed with 200 feet of fencing. \medskip The problem of solving a maximum or minimum problem consists of setting up the function to be maximized or minimized and then taking derivatives. The theorems of this section tell how to proceed from there.

Example

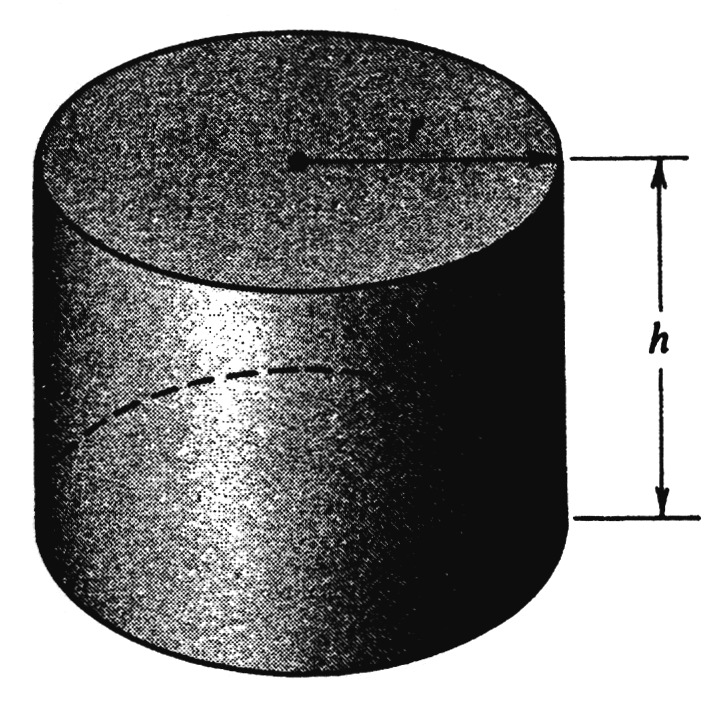

What are the dimensions of the cylindrical quart can which can be made from the least amount of tin? This problem is important to the manufacturer who produces tin cans and is more concerned with the amount of tin used than with the shape of the can. Should he make tall cans with a small radius or short cans with a large radius? We shall ignore seams and assume that tin cans are perfect cylinders. The volume of a cylinder is [math]\pi {r^2}h[/math] and a quart contains [math]57\frac{3}{4}[/math] cubic inches. Thus if [math]r[/math] is the radius of the can in inches and [math]h[/math] is the height in inches, [math]\pi {r^2}h = 57 \frac{3}{4}[/math] or [math]\frac{231}{4}[/math](see Figure). The area is the sum of the lateral surface area and the area of the bottom and the top: [math]A = 2\pi rh + 2\pi {r^2}[/math]. The area depends on [math]r[/math] and [math]h[/math], but we can use our volume equation to find [math]h[/math] as a function of [math]r: h = \frac{231}{4\pi {r^2}}[/math], and then write

The domain of [math]A[/math] is the set of positive real numbers. Taking derivatives, we have [math]A'(r) = - \frac{231}{2r^2} + 4 \pi r[/math] and [math]A''(r) = \frac{231}{r^2} + 4 \pi[/math]. Setting [math]A'[/math] equal to zero, we have [math]8 \pi r^3 = 231[/math], or [math]r = \frac{1}{2} \sqrt[3]{\frac{231}{\pi}} = 2.10[/math] (approximately). Since [math]A'(2.10) = 0[/math] and [math]A''(2.10) \gt 0[/math], 2.10 gives a minimum value to [math]A[/math]. [math]h = \frac{231}{4 \pi (2.10)^2} = 4.20[/math] (approximately). The desired can will look square in profile, 2.10 inches in radius and 4.20 inches high. This problem could also have been solved by writing [math]r[/math] as a function of [math]h: r = \sqrt{\frac{231}{4\pi h}}[/math] and then writing [math]A(h) = 2\pi \sqrt {\frac{231}{4\pi h}} h + 2\pi \cdot \frac{231}{4\pi h}[/math], although this area function is not as nice as [math]A(r)[/math]. Another method involves thinking of [math]h[/math] as a function of [math]r[/math], writing [math]A(r)[/math] containing both [math]h[/math] and [math]r[/math], and differentiating implicity. Thus we write

Differentiating with respect to [math]r[/math], we obtain

From the first, [math]\frac{dh}{dr} = -\frac{2 \pi rh}{\pi r^2} = -\frac{2h}{r}[/math]. Substituting this in the second, we find [math]A'(r) = 2 \pi r \Bigl( -\frac{2h}{r} \Bigr) + 2 \pi h + 4 \pi r = 4 \pi r - 2\pi h[/math]. Setting [math]A'(r) = 0[/math], we get

Substitution in the volume equation yields [math]\pi r^{2}(2r) = \frac{231}{4}[/math], or [math]8 \pi r^3 = 231[/math], as in the other solution. This same method could have been used with differentiation with respect to [math]h[/math]. In each of the preceding examples, the domain of the function was an interval of positive real numbers. However, if a problem involves the number of objects which will maximize or minimize a particular function, it will have a domain of positive integers. In this case, we may still do the problem as if it were one with the entire set of real numbers as the domain of the function, and then consider those positive integers which lie on either side of the [math]x[/math]-coordinate of the critical point of this function.

Example

A telephone company which serves a small community makes an annual profit of \$12 per subscriber if it has 725 subscribers or fewer. They decide to reduce the rate by a fixed sum for each subscriber over 725, thereby reducing the profit I cent per subscriber. Thus there will be a profit of \$11.99 on each of 726 subscribers, \$11.98 on each of 727, etc. What is the number of subscribers which will give them the greatest profit? If we let [math]x[/math] be the number of subscribers over 725, there will then be [math]725 + x[/math] subscribers and the profit per subscriber will be [math]1200 - x[/math] cents. The total profit will be [math]P(x) = (725 + x)(1200 - x) = 870,000 + 475x - x^2[/math]. The domain of [math]P[/math] is the set of positive integers, but let us treat the problem as if the domain were [math]R[/math]. The derivatives are [math]P'(x)= 475 - 2x[/math] and [math]P''(x) = -2[/math]. The value of [math]x[/math] which makes [math]P'[/math] zero is [math]237\frac{1}{2}[/math], and it also makes [math]P''[/math] negative, thereby ensuring a maximum for [math]P[/math]. We find [math]P(237) = 926,406[/math] and [math]P(238) = 926,406[/math]. Thus the profit is the same for 725 + 237 = 962 subscribers and for 725 + 238 = 963 subscribers. If we visualize the graph of [math]P[/math], we see a parabola concave downward with its maximum point at [math](237\frac{1}{2}, 926,406\frac{1}{4})[/math]. If we delete all points which do not have integral coefficients, then the points (237, 926,406) and (238, 926,406) are maximum points equally spaced on either side of the high point of the parabola and just lower than the high point. The profit of the telephone company will increase with each new subscriber until they have 962 subscribers. The addition of one more subscriber will not alter the profit, but it will then decrease with each new subscriber after the 963rd one.

Example

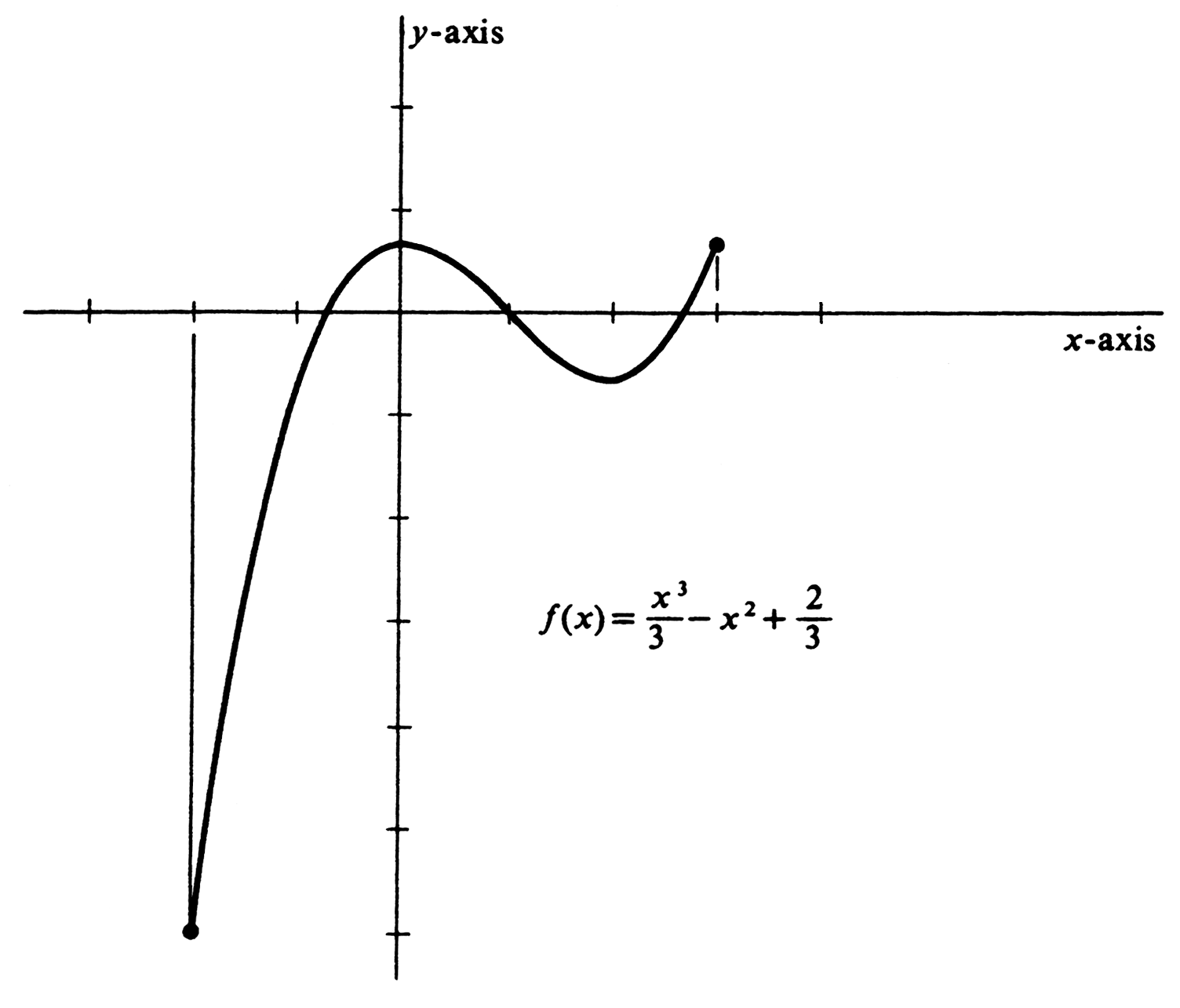

Consider the function [math]f[/math] defined by

The domain of [math]f[/math] is the closed interval [math][-2, 3][/math]. Find the maximum and minimum values. The derivatives are [math]f'(x) = x^2 - 2x = x(x - 2)[/math] and [math]f''(x) = 2x - 2 = 2(x - 1)[/math]. Setting [math]f'(x) = 0[/math], we find solutions [math]x = 0[/math] and [math]x = 2[/math]. By Theorem (2.3) we need evaluate [math]f(x)[/math] only where [math]x = 0[/math] and [math]x = 2[/math] [where [math]f'(x) = 0[/math]] and at the endpoints of the interval, [math]x = -2[/math] and [math]x = 3[/math]. These values are

Thus the maximum value of [math]f[/math] is [math]\frac{2}{3}[/math], and the minimum value is [math]-6[/math]. Note that the maximum value of the function occurs at two points, one of which is a local maximum and the other the right endpoint of the interval. The minimum

value, on the other hand, does not occur at a local minimum point, but at the Ieft endpoint. The graph of the function is shown in Figure.

We summarize the techniques for solving maximum and minimum problems as follows:

- Set up the function to be maximized or minimized. If it can easily be set up as a function of one variable, it should be. If it cannot easily be set up as a function of one variable, it should be accompanied by an equation relating the two variables.

- Take first and second derivatives of the function. Set the first derivative equal to zero and solve the resulting equation. Evaluate the second derivative at those values of [math]x[/math] for which the first derivative equals zero.

- If the function is a “nice” function defined on an open interval, its maximum will occur where [math]f'(x) = 0[/math] and [math]f''(x) \lt 0[/math] and its minimum will occur where [math]f'(x) = 0[/math] and [math]f''(x) \gt 0[/math].

- If the function has a closed interval for its domain, evaluate the function at both endpoints to see if maximum or minimum values occur there.

- If the function has a domain restricted to integers, evaluate the function at integers near the values which give a maximum or a minimum value to the continuous function.

Sometimes the geometric or physical properties of the problem make it obvious that a critical point is of the desired type, i.e., a maximum or a minimum. If this happens, it is not necessary to compute the second derivative, although it may still be used as a check. The complete behavior of the function whose extreme points are desired can always be found by carefully plotting its graph.

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.