guide:Cf8f672ed4: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="d-none"><math> | |||

\newcommand{\ex}[1]{\item } | |||

\newcommand{\sx}{\item} | |||

\newcommand{\x}{\sx} | |||

\newcommand{\sxlab}[1]{} | |||

\newcommand{\xlab}{\sxlab} | |||

\newcommand{\prov}[1] {\quad #1} | |||

\newcommand{\provx}[1] {\quad \mbox{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\intext}[1]{\quad \mbox{#1} \quad} | |||

\newcommand{\R}{\mathrm{\bf R}} | |||

\newcommand{\Q}{\mathrm{\bf Q}} | |||

\newcommand{\Z}{\mathrm{\bf Z}} | |||

\newcommand{\C}{\mathrm{\bf C}} | |||

\newcommand{\dt}{\textbf} | |||

\newcommand{\goesto}{\rightarrow} | |||

\newcommand{\ddxof}[1]{\frac{d #1}{d x}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddx}{\frac{d}{dx}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddt}{\frac{d}{dt}} | |||

\newcommand{\dydx}{\ddxof y} | |||

\newcommand{\nxder}[3]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{d{#3}^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\deriv}[2]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{dx^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\dist}{\mathrm{distance}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccot}{\mathrm{arccot\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccsc}{\mathrm{arccsc\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsec}{\mathrm{arcsec\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arctanh}{\mathrm{arctanh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsinh}{\mathrm{arcsinh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccosh}{\mathrm{arccosh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\sech}{\mathrm{sech\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\csch}{\mathrm{csch\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\conj}[1]{\overline{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb} | |||

</math></div> | |||

The other trigonometric functions are the tangent, cotangent, secant, and cosecant. They are abbreviated <math>\tan</math>, <math>\cot</math> (or ctn), <math>\sec</math>, and <math>\csc</math>, respectively, and the definitions are | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{array}{ll} | |||

\tan x = \frac{\sin x}{\cos x} & \sec x = \frac{1}{\cos x}\\ | |||

\\ | |||

\cot x = \frac{\cos x}{\sin x} & \csc x = \frac{1}{\sin x}. | |||

\end{array} | |||

</math> | |||

Unlike <math>\sin</math> and <math>\cos</math>, these functions are not defined for all real values of <math>x</math> since the | |||

denominators in the defining expressions are zero for some values of <math>x</math>. The set of all solutions | |||

to the equation <math>\cos x = 0</math> is the set consisting of all odd multiples of <math>\frac{\pi}{2}</math> . | |||

Hence <math>\tan x</math> and <math>\sec x</math> are defined if and only if <math>x</math> is not an odd multiple of <math>\frac{\pi}{2}</math>. Similarly, <math>\cot x</math> and <math>\csc x</math> are defined for all real numbers <math>x</math> except integer multiples of <math>\pi</math>. | |||

Although sine and cosine were first defined with a domain of real numbers, we have shown that | |||

they also can be considered as functions with a domain of angles. Since the other four functions | |||

are defined in terms of sine and cosine, they may also be regarded as functions with a domain of | |||

angles. Thus it makes sense to speak of the tangent of the angle <math>\alpha</math>, written <math>\tan \alpha</math>, | |||

and of the cosecant of an angle of <math>30^{\circ}</math>, written <math>\csc 30^{\circ}</math>. The former is defined if | |||

and only if the radian measure of <math>\alpha</math> is not an odd multiple of <math>\frac{\pi}{2}</math> or, alternatively, | |||

if the degree measure of <math>\alpha</math> is not an odd multiple of 90. The latter is the reciprocal of | |||

<math>\sin 30^{\circ}</math> and is equal to <math>\frac{1}{\frac{1}{2}} = 2</math>. | |||

Two useful trigonometric identities, which are simply alternative statements of the basic equation <math>\cos^{2}x + \sin^{2}x = 1</math>, are derived as follows: | |||

Dividing first by <math>\cos^{2}x</math>, we have | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{array}{ccccc} | |||

\frac{\cos^{2}x}{\cos^{2} x} &+& \frac{ \sin^{2} x }{\cos ^{2} x} &=& \frac{1}{\cos^{2}{x}}\\ | |||

\\ | |||

|| & & || & & ||\\ | |||

\\ | |||

1 & & \tan^{2} x & & \sec^{2}x, | |||

\end{array} | |||

</math> | |||

hence <math>1 + \tan^{2}x = \sec^{2}x</math>. On the other hand, if we divide by <math>\sin^{2}x</math>, we have | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{array}{ccccc} | |||

\frac{\cos^{2}x}{\sin^{2} x} &+& \frac{ \sin^{2} x }{\sin ^{2} x} &=& \frac{1}{\sin^{2}{x}}\\ | |||

\\ | |||

|| & & || & & ||\\ | |||

\\ | |||

\cot^{2} x & & 1 & & \csc^{2}x, | |||

\end{array} | |||

</math> | |||

and so <math>\cot^{2}x + 1 = \csc^{2}x</math>. Summarizing, we write | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-1| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

1 +\tan^{2}x &=& \sec^{2}x, \\ | |||

\cot^{2}x + 1 &=& \csc^{2}x. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math>|}} | |||

Another formula which we shall find useful is that for the tangent of the difference of two numbers, <math>a - b</math>, in terms of <math>\tan a</math> and <math>\tan b</math>. First, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\tan (a - b) = \frac{\sin (a - b)}{\cos(a - b)} = \frac{\sin a \cos b - \cos a \sin b}{\cos a \cos b + \sin a \sin b}. | |||

</math> | |||

Dividing both numerator and denominator by <math>\cos a \cos b</math>, we get | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\tan (a - b) &=& \frac{\frac{\sin a \cos b}{\cos a \cos b} - \frac{\cos a \sin b}{\cos a \cos b}}{\frac{\cos a \cos b}{\cos a \cos b} + \frac{\sin a \sin b}{\cos a \cos b}}\\ | |||

&=& \frac{\frac{\sin a}{\cos a} - \frac{\sin b}{\cos b}}{ 1 + \frac{\sin a}{\cos a} \frac{\sin b}{\cos b}} . | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

Hence | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-2| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\tan(a-b) = \frac{\tan a - \tan b}{1 + \tan a \tan b}. | |||

</math>|}} | |||

The trigonometric identities developed in this section are handy tools, and we shall not hesitate | |||

to use them. In themselves, however, they are of secondary importance. Any one of them can be | |||

derived quickly and in a completely routine way from the basic identities in <math>\sin</math> and <math>\cos</math> derived | |||

in Section 1. | |||

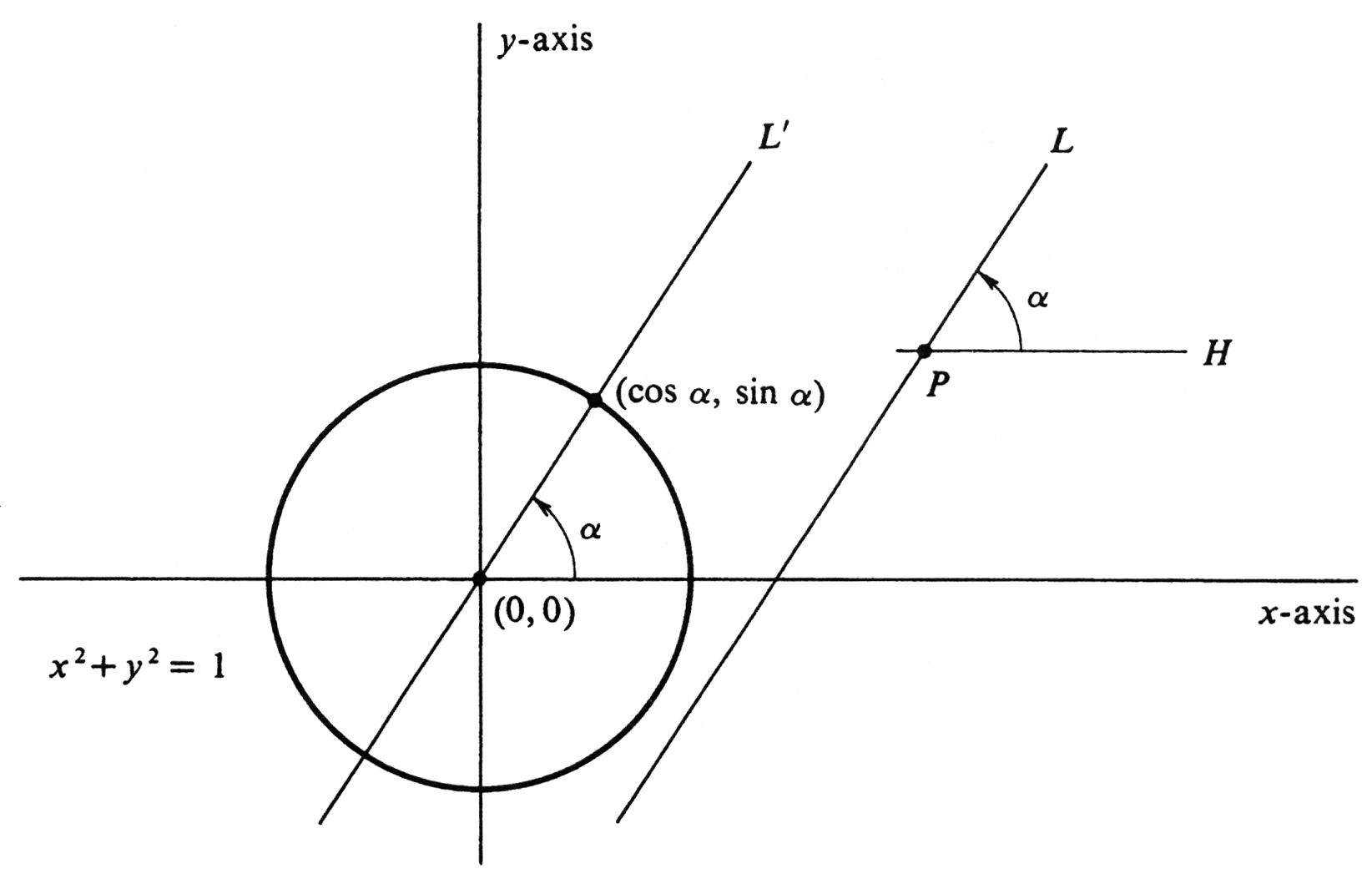

An important application of the tangent function is in connection with the slope of a straight line. We define the angle of inclination <math>\alpha</math> of a straight line <math>L</math> as follows: If <math>L</math> is horizontal, then <math>\alpha = 0</math>. If <math>L</math> is not horizontal, then it intersects an arbitrary horizontal line <math>H</math> in a single point <math>P</math>. Let <math>\alpha</math> be the angle with vertex <math>P</math>, initial side the part of <math>H</math> to the right of <math>P</math>, terminal side the part of <math>L</math> above <math>P</math>, and whose measure in radians satisfies the inequality <math>0 < \alpha < \pi</math> (see Figure 10). We contend that | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-3|The slope of a line is equal to the tangent of its angle of inclination. | |||

|We refer again to Figure 10. The given line is <math>L</math>, its inclination is <math>\alpha</math>, and its slope is <math>m</math>. If <math>L'</math> is drawn through the origin parallel to <math>L</math>, then <math>L'</math> also has | |||

inclination <math>\alpha</math> and slope <math>m</math>. Furthermore, the point <math>(\cos \alpha, \sin \alpha)</math> lies on <math>L'</math>. | |||

Since (0,0) also lies on <math>L'</math>, the definition of slope yields | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

m = \frac{\sin \alpha - 0}{\cos \alpha - 0} = \frac{\sin \alpha}{\cos \alpha} = \tan \alpha, | |||

</math> | |||

which completes the proof. If <math>L</math> is vertical, its slope is not defined. But then the angle of inclination is <math>\frac{\pi}{2}</math> and <math>\tan\frac{\pi}{2}</math> is not defined either.}} | |||

<div id="fig 6.10" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig6_10.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

<div id="fig 6.11" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig6_11.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

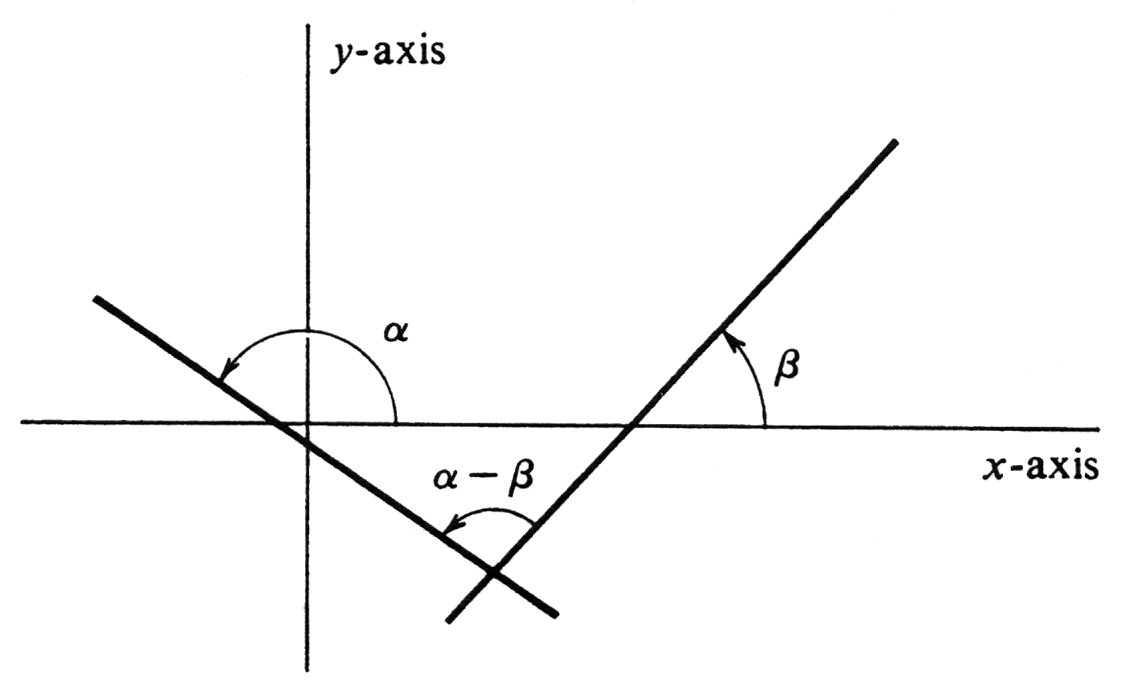

The importance of (3.2) is apparent when we try to determine the angle between two nonvertical intersecting lines. Let <math>\alpha</math> be the angle of inclination of one line and, <math>\beta</math> the angle of inclination of the other. For convenience, we assume that <math>\alpha > \beta</math>. It follows that <math>0 < \alpha - \beta < \pi</math> and, from Figure 11 | |||

that the difference <math>\alpha - \beta</math> is an angle between the two lines. We denote the slope of the first line by <math>m_{1}</math>, and that of the second by <math>m_{2}</math>. That is, we have <math>m_{1} = \tan \alpha</math> and <math>m_{2} = \tan \beta</math>. By (3.2), | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\tan (\alpha - \beta) = \frac{\tan \alpha - \tan \beta}{1 + \tan \alpha \tan\beta} = \frac{m_{1} - m_{2}}{1 + m_{1}m_{2}}. | |||

</math> | |||

If this number is positive, then <math>\alpha - \beta</math> is the acute angle between the lines. If this number is negative, then <math>\alpha - \beta</math> is the obtuse angle between the lines. If this number is unclefined, then <math>\alpha - \beta = \frac{\pi}{2}</math> and the lines are perpendicular. The number <math>\frac{m_{1} - m_{2}}{1 + m_{1}m_{2}}</math> is unclefined if and only if <math>1 + m_{1}m_{2} = 0</math>. Since this equation is equivalent to <math>m_{1} m_{2} = - 1</math>, it follows that we have proved the statement made on page 44 that two nonvertical lines with slopes <math>m_{1}</math> and <math>m_{2}</math>, are perpendicular if and only if <math>m_{1}m_{2} = - 1</math>. | |||

The formulas for the derivatives of the remaining four trigonometric functions are found using | |||

the derivatives of <math>\sin</math> and <math>\cos</math> together with the usual rules of differentiation. They are | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-4| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\frac{d}{dx} \tan x &=& \sec^{2}x,\\ | |||

\frac{d}{dx} \cot x &=& - \csc^{2}x,\\ | |||

\frac{d}{dx} \sec x &=& \sec x \tan x, \\ | |||

\frac{d}{dx} \csc x &=& - \csc x \cot x. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math>|}} | |||

Proving the first of these, we have | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\frac{d}{dx} \tan x &=& \frac{d}{dx} \frac{\sin x}{\cos x} = \frac{\cos x \frac{d}{dx} \sin x - \sin x \frac{d}{dx} \cos x}{\cos^{2} x} \\ | |||

&=& \frac{\cos^{2} x + \sin^{2} x}{\cos ^{2} x} = \frac{1}{\cos^{2} x} = \sec^{2} x. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

The others are left as exercises. We observe the following mnemonic device. | |||

From any one of the six formulas for differentiating trigonometric functions another one is obtained by adding the prefix “co” to every function which does not have one, removing the prefix “co” from each function which has it already, and changing the sign. For example, this procedure transforms the equation <math>\frac{d}{dx} \sec x = \sec x \tan x</math> into <math>\frac{d}{dx} \csc x= -\csc x \cot x</math> and transforms | |||

<math>\frac{d}{dx} \cos x = - \sin x</math> into <math>\frac{d}{dx} \sin x= \cos x</math>. Hence the number of derivative formulas which need to be memorized can be cut in half. | |||

The integrals corresponding to the above derivatives are | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-5| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

&\int&\sec^{2}x dx = \tan x + c,\\ | |||

&\int&\csc^{2}x dx = -\cot x + c,\\ | |||

&\int&\sec x \tan x dx = \sec x + c,\\ | |||

&\int&\csc x\cot x dx = - \csc x + c. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math>|}} | |||

'''Example''' | |||

Find the following integrals: | |||

<ul style="list-style-type:lower-alpha"> | |||

<li> | |||

<math>\int x^{2} \sec^{2} (x^{3} + 1 ) dx,</math> | |||

</li> | |||

<li> | |||

<math>\int \tan x dx,</math> | |||

</li> | |||

<li> | |||

<math>\int \csc^{2}x \cot^{5}x dx.</math> | |||

</li> | |||

</ul> | |||

In (a) we observe that <math>\frac{d}{dx}(x^{3} + 1) = 3x^{2}</math>, or, equivalently, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

x^2 = \frac{1}{3} \frac{d}{dx} (x^{3} + 1). | |||

</math> | |||

Hence | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\int x^{2} \sec^{2}(x^{3} + 1) dx &=& \frac{1}{3} \int [\sec^{2} (x^{3} + 1)] \frac{d}{dx} (x^{3} + 1)dx\\ | |||

&=& \frac{1}{3} \tan (x^{3}+ 1) + c. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

For (b), we have <math>\int \tan x dx = \int \frac{\sin x}{\cos x} dx</math>. If <math>u = \cos x</math>, then | |||

<math>\frac{du}{dx} = -\sin x</math>, and so | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\int \tan x dx &=& \int \frac{\sin x}{\cos x} dx = - \int \frac{1}{u} \frac{du}{dx} dx\\ | |||

&=& - \ln |u| + c = - \ln |\cos x| + c. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

Finally, to do (c), we see that since <math>\frac{d}{dx} \cot x = - \csc^{2}x</math>, the integral is, | |||

except for a minus sign, of the form <math>\int u^{5} \frac{du}{dx} dx</math>. Thus | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\int \csc^{2} x \cot^{5}x dx &=& - \int (\cot^{5}x) \frac{d}{dx} \cot x dx\\ | |||

&=& - \frac{1}{6} \cot^{6}x + c. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

Each of these integrals can be checked by differentiation. | |||

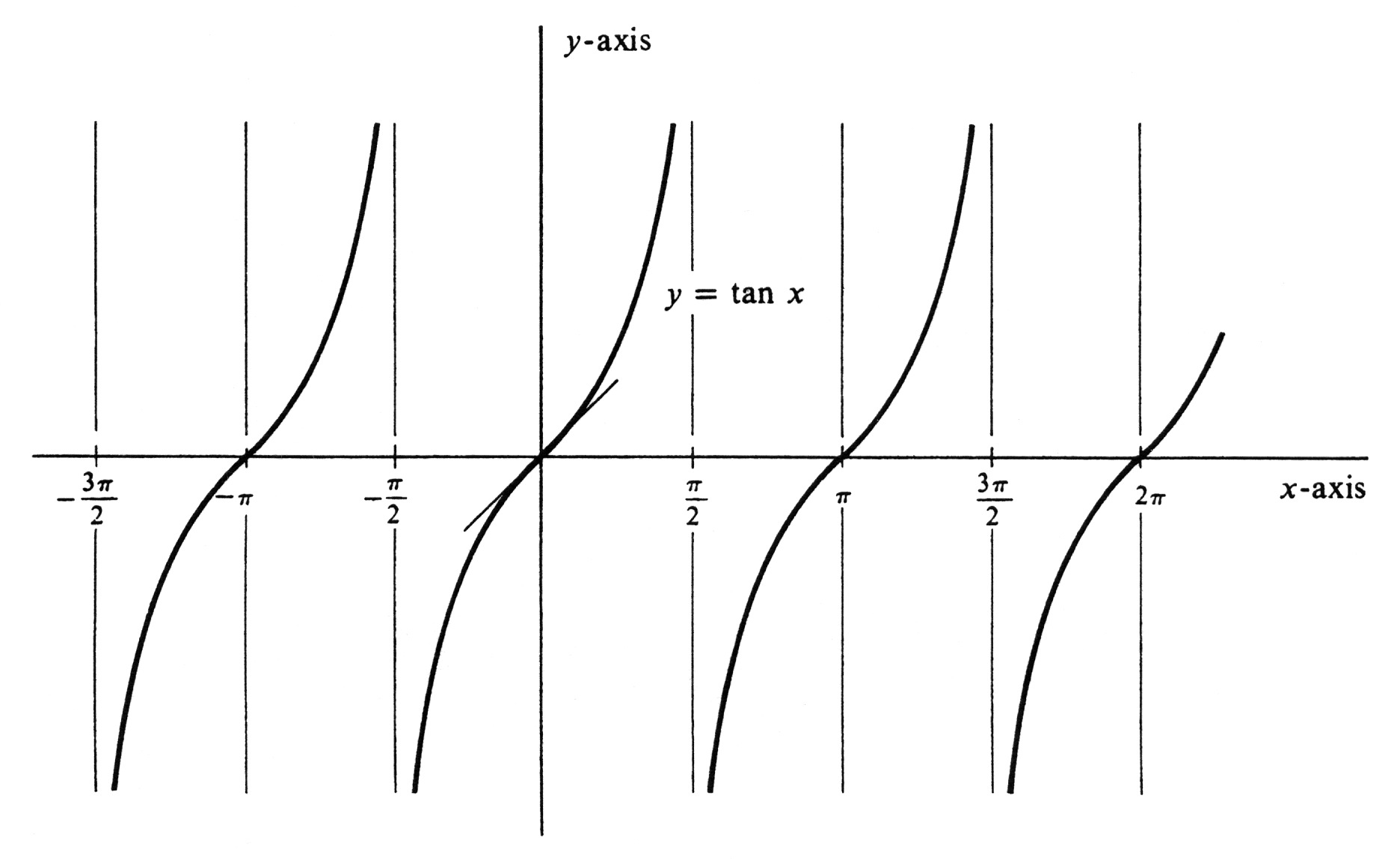

The graph of <math>\tan x</math> is an interesting curve, which we now describe. Note, first of all, that <math>\tan</math> is an odd function, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\tan(-x) = \frac{\sin(-x)}{\cos(-x)} = \frac{-\sin x}{\cos x} = - \tan x, | |||

</math> | |||

and the graph is therefore symmetric about the origin. Moreover, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\tan(x + \pi) &=& \frac{\sin(x + \pi) }{\cos ( x + \pi)} = \frac{\sin x \cos \pi + \cos x \sin \pi} | |||

{\cos x \cos \pi - \sin x \sin \pi} \\ | |||

&=& \frac{-\sin x}{-\cos x} = \tan x. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

Thus <math>\tan</math> is a periodic function with period <math>\pi</math>. The slope of the graph is given by the derivative, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\frac{d}{dx}\tan x = \sec^{2}x, | |||

</math> | |||

which is positive for every value of <math>x</math> for which <math>\tan x</math> is defined. Hence <math>\tan x</math> is a strictly increasing function in the interval <math>-\frac{\pi}{2} < x < \frac{\pi}{2}</math>. From the definition, <math>\tan x = \frac{\sin x}{\cos x}</math>, we see that <math>\tan x</math> is positive when both functions <math>\cos x</math> are positive, as they are for <math>0 < x < \frac{\pi}{2}</math>; is zero when <math>\sin x = 0</math>, as it is for <math>x = 0</math>; and is negative when the two functions have opposite sign, as they do for <math>-\frac{\pi}{2} < x < 0</math>. We also see that <math>\tan x </math> takes on arbitrarily large positive values as <math>x</math> approaches <math>\frac{\pi}{2}</math> from the left, since <math>\sin x</math> approaches 1 and <math>\cos x</math> approaches 0. Thus | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\lim_{x \rightarrow \frac{\pi}{2}-} \tan x = \infty. | |||

</math> | |||

The second derivative is given by | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\frac{d^2}{dx^2} \tan x = 2 \sec^{2} x \tan x = \left\{ | |||

\begin{array}{ll} | |||

< 0 & \;\;\;\mbox{if}\; - \frac{\pi}{2} < x < 0,\\ | |||

= 0 & \;\;\;\mbox{if}\; x = 0, \\ | |||

> 0 & \;\;\;\mbox{if}\; 0 < x < \frac{\pi}{2}, | |||

\end{array} | |||

\right . | |||

</math> | |||

from which it follows that the graph is concave downward for <math>-\frac{\pi}{2} < x < 0</math>, | |||

concave upward for <math>0 < x < \frac{\pi}{2}</math> and has a point of inflection at the origin. | |||

Combining all these facts with the few isolated values shown in Table 3, we obtain the graph | |||

shown in Figure 12. | |||

<div id="fig 6.12" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig6_12.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

<span id="table 6.3"/> | |||

{|class="table" | |||

|- | |||

|<math>x</math> || <math>y</math> = <math>\tan x</math> || <math>\frac{dy}{dx} = \sec^{2}x</math> | |||

|- | |||

|0 || 0 || 1 | |||

|- | |||

|<math>\frac{\pi}{6}</math> || <math>\frac{1}{\sqrt 3}</math> = 0.58 (approx.) || <math>\frac{4}{3}</math> = 1.33 (approx.) | |||

|- | |||

|<math>\frac{\pi}{4}</math> || 1 || 2 | |||

|- | |||

|<math>\frac{\pi}{3}</math> || <math>\sqrt 3</math> = 1.73 (approx.) || 4 | |||

|} | |||

The graph of <math>\cot x</math> can be obtained in the same way in which we worked out the graph of <math>\tan x</math>. However, there is a quicker way based on an identity. Since | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\tan \Bigl(x + \frac{\pi}{2} \Bigr) &=& \frac{\sin \Bigl(x + \frac{\pi}{2} \Bigr)}{ \cos \Bigl(x + \frac{\pi}{2} \Bigr)} | |||

= \frac{\sin x \cos \frac{\pi}{2} + \cos x \sin \frac{\pi}{2}}{ \cos x \cos\frac{\pi}{2} | |||

- \sin x \sin \frac{\pi}{2}} \\ | |||

&=& \frac{\cos x}{-\sin x} = - \cot x , | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

we know that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\cot x = - \tan \Bigl(x + \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr) . | |||

</math> | |||

The geometric significance of this identity is that the graph of <math>\cot x</math> is obtained by translating (sliding) the graph of <math>\tan x</math> to the left a distance <math>\frac{\pi}{2}</math> and then reflecting about the <math>x</math>-axis. | |||

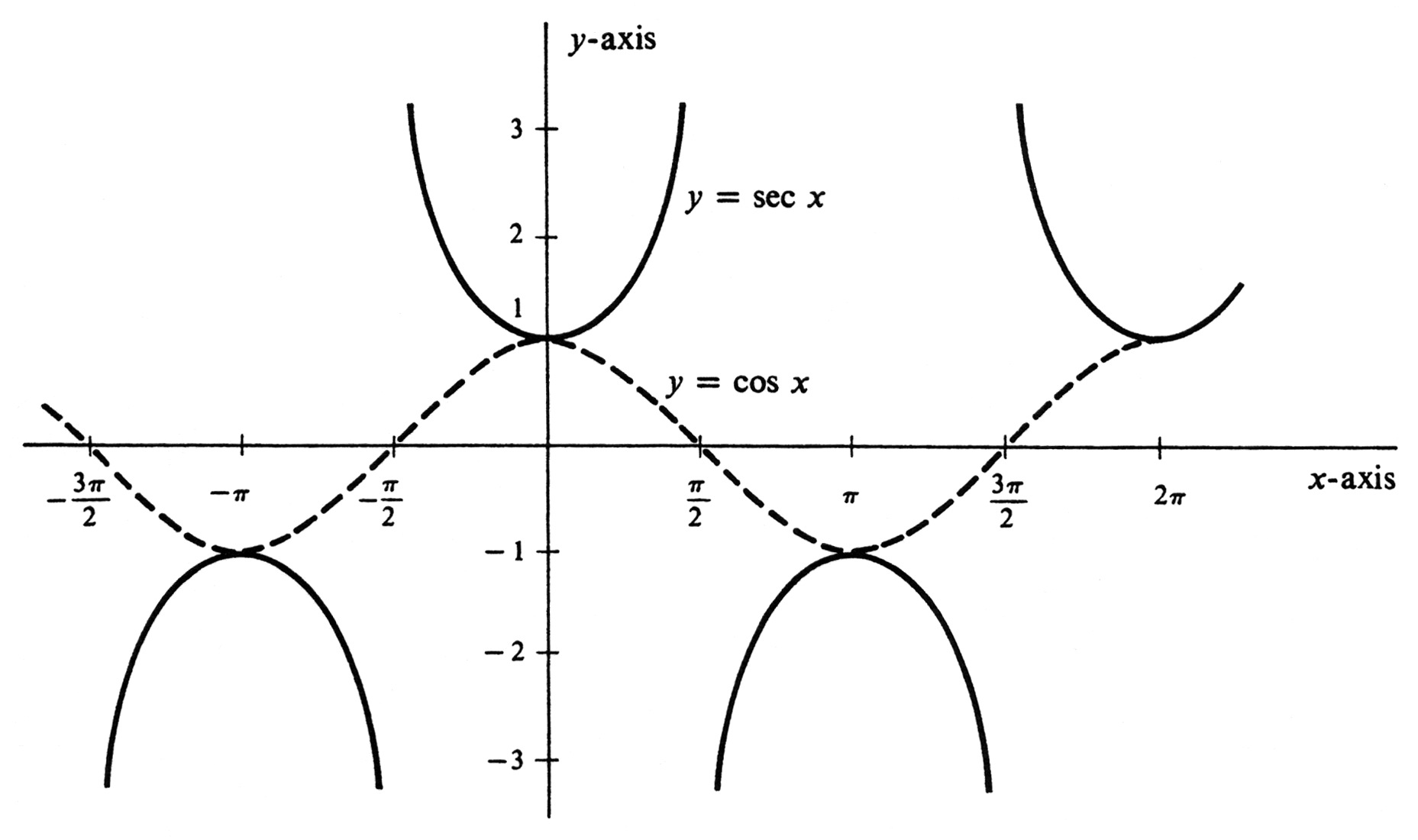

From the definition, <math>\sec x = \frac{1}{\cos x}</math>, it is apparent that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\sec n \pi = \frac{1}{\cos n\pi} = \{ \begin{array}{rl} | |||

1 &\;\;\; \mbox{if $n$ is even}, \\ | |||

-1 & \;\;\; \mbox{if $n$ is odd}. | |||

\end{array} | |||

</math> | |||

If <math>a</math> is any odd multiple of <math>\frac{\pi}{2}</math>, then <math>\cos a = 0</math>, and so | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\lim_{x \rightarrow a} |\sec x| = \lim_{x \rightarrow a} \frac{1}{|\cos x|} = \infty. | |||

</math> | |||

<div id="fig 6.13" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig6_13.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

Moreover, on an interval where one function is increasing, its reciprocal function is decreasing, and vice versa. It follows that the over-all shape of the graph of <math>\sec x</math> can be ascertained quite easily from the graph of its reciprocal function <math>\cos x</math>. The graph of <math>\sec x</math> is shown in Figure 13. | |||

The graph of <math>\csc x</math> is related to that of <math>\sec x</math> in the same way as the graph of <math>\sin x</math> is related to the graph of <math>\cos x</math>. | |||

==General references== | |||

{{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | |||

Latest revision as of 19:59, 19 November 2024

The other trigonometric functions are the tangent, cotangent, secant, and cosecant. They are abbreviated [math]\tan[/math], [math]\cot[/math] (or ctn), [math]\sec[/math], and [math]\csc[/math], respectively, and the definitions are

Unlike [math]\sin[/math] and [math]\cos[/math], these functions are not defined for all real values of [math]x[/math] since the denominators in the defining expressions are zero for some values of [math]x[/math]. The set of all solutions to the equation [math]\cos x = 0[/math] is the set consisting of all odd multiples of [math]\frac{\pi}{2}[/math] . Hence [math]\tan x[/math] and [math]\sec x[/math] are defined if and only if [math]x[/math] is not an odd multiple of [math]\frac{\pi}{2}[/math]. Similarly, [math]\cot x[/math] and [math]\csc x[/math] are defined for all real numbers [math]x[/math] except integer multiples of [math]\pi[/math]. Although sine and cosine were first defined with a domain of real numbers, we have shown that they also can be considered as functions with a domain of angles. Since the other four functions are defined in terms of sine and cosine, they may also be regarded as functions with a domain of angles. Thus it makes sense to speak of the tangent of the angle [math]\alpha[/math], written [math]\tan \alpha[/math], and of the cosecant of an angle of [math]30^{\circ}[/math], written [math]\csc 30^{\circ}[/math]. The former is defined if and only if the radian measure of [math]\alpha[/math] is not an odd multiple of [math]\frac{\pi}{2}[/math] or, alternatively, if the degree measure of [math]\alpha[/math] is not an odd multiple of 90. The latter is the reciprocal of [math]\sin 30^{\circ}[/math] and is equal to [math]\frac{1}{\frac{1}{2}} = 2[/math]. Two useful trigonometric identities, which are simply alternative statements of the basic equation [math]\cos^{2}x + \sin^{2}x = 1[/math], are derived as follows: Dividing first by [math]\cos^{2}x[/math], we have

hence [math]1 + \tan^{2}x = \sec^{2}x[/math]. On the other hand, if we divide by [math]\sin^{2}x[/math], we have

and so [math]\cot^{2}x + 1 = \csc^{2}x[/math]. Summarizing, we write

Another formula which we shall find useful is that for the tangent of the difference of two numbers, [math]a - b[/math], in terms of [math]\tan a[/math] and [math]\tan b[/math]. First,

Dividing both numerator and denominator by [math]\cos a \cos b[/math], we get

Hence

The trigonometric identities developed in this section are handy tools, and we shall not hesitate to use them. In themselves, however, they are of secondary importance. Any one of them can be derived quickly and in a completely routine way from the basic identities in [math]\sin[/math] and [math]\cos[/math] derived in Section 1. An important application of the tangent function is in connection with the slope of a straight line. We define the angle of inclination [math]\alpha[/math] of a straight line [math]L[/math] as follows: If [math]L[/math] is horizontal, then [math]\alpha = 0[/math]. If [math]L[/math] is not horizontal, then it intersects an arbitrary horizontal line [math]H[/math] in a single point [math]P[/math]. Let [math]\alpha[/math] be the angle with vertex [math]P[/math], initial side the part of [math]H[/math] to the right of [math]P[/math], terminal side the part of [math]L[/math] above [math]P[/math], and whose measure in radians satisfies the inequality [math]0 \lt \alpha \lt \pi[/math] (see Figure 10). We contend that

The slope of a line is equal to the tangent of its angle of inclination.

We refer again to Figure 10. The given line is [math]L[/math], its inclination is [math]\alpha[/math], and its slope is [math]m[/math]. If [math]L'[/math] is drawn through the origin parallel to [math]L[/math], then [math]L'[/math] also has inclination [math]\alpha[/math] and slope [math]m[/math]. Furthermore, the point [math](\cos \alpha, \sin \alpha)[/math] lies on [math]L'[/math]. Since (0,0) also lies on [math]L'[/math], the definition of slope yields

The importance of (3.2) is apparent when we try to determine the angle between two nonvertical intersecting lines. Let [math]\alpha[/math] be the angle of inclination of one line and, [math]\beta[/math] the angle of inclination of the other. For convenience, we assume that [math]\alpha \gt \beta[/math]. It follows that [math]0 \lt \alpha - \beta \lt \pi[/math] and, from Figure 11 that the difference [math]\alpha - \beta[/math] is an angle between the two lines. We denote the slope of the first line by [math]m_{1}[/math], and that of the second by [math]m_{2}[/math]. That is, we have [math]m_{1} = \tan \alpha[/math] and [math]m_{2} = \tan \beta[/math]. By (3.2),

If this number is positive, then [math]\alpha - \beta[/math] is the acute angle between the lines. If this number is negative, then [math]\alpha - \beta[/math] is the obtuse angle between the lines. If this number is unclefined, then [math]\alpha - \beta = \frac{\pi}{2}[/math] and the lines are perpendicular. The number [math]\frac{m_{1} - m_{2}}{1 + m_{1}m_{2}}[/math] is unclefined if and only if [math]1 + m_{1}m_{2} = 0[/math]. Since this equation is equivalent to [math]m_{1} m_{2} = - 1[/math], it follows that we have proved the statement made on page 44 that two nonvertical lines with slopes [math]m_{1}[/math] and [math]m_{2}[/math], are perpendicular if and only if [math]m_{1}m_{2} = - 1[/math]. The formulas for the derivatives of the remaining four trigonometric functions are found using the derivatives of [math]\sin[/math] and [math]\cos[/math] together with the usual rules of differentiation. They are

Proving the first of these, we have

The others are left as exercises. We observe the following mnemonic device.

From any one of the six formulas for differentiating trigonometric functions another one is obtained by adding the prefix “co” to every function which does not have one, removing the prefix “co” from each function which has it already, and changing the sign. For example, this procedure transforms the equation [math]\frac{d}{dx} \sec x = \sec x \tan x[/math] into [math]\frac{d}{dx} \csc x= -\csc x \cot x[/math] and transforms

[math]\frac{d}{dx} \cos x = - \sin x[/math] into [math]\frac{d}{dx} \sin x= \cos x[/math]. Hence the number of derivative formulas which need to be memorized can be cut in half.

The integrals corresponding to the above derivatives are

Example Find the following integrals:

- [math]\int x^{2} \sec^{2} (x^{3} + 1 ) dx,[/math]

- [math]\int \tan x dx,[/math]

- [math]\int \csc^{2}x \cot^{5}x dx.[/math]

In (a) we observe that [math]\frac{d}{dx}(x^{3} + 1) = 3x^{2}[/math], or, equivalently,

Hence

For (b), we have [math]\int \tan x dx = \int \frac{\sin x}{\cos x} dx[/math]. If [math]u = \cos x[/math], then

[math]\frac{du}{dx} = -\sin x[/math], and so

Finally, to do (c), we see that since [math]\frac{d}{dx} \cot x = - \csc^{2}x[/math], the integral is,

except for a minus sign, of the form [math]\int u^{5} \frac{du}{dx} dx[/math]. Thus

Each of these integrals can be checked by differentiation.

The graph of [math]\tan x[/math] is an interesting curve, which we now describe. Note, first of all, that [math]\tan[/math] is an odd function,

and the graph is therefore symmetric about the origin. Moreover,

Thus [math]\tan[/math] is a periodic function with period [math]\pi[/math]. The slope of the graph is given by the derivative,

which is positive for every value of [math]x[/math] for which [math]\tan x[/math] is defined. Hence [math]\tan x[/math] is a strictly increasing function in the interval [math]-\frac{\pi}{2} \lt x \lt \frac{\pi}{2}[/math]. From the definition, [math]\tan x = \frac{\sin x}{\cos x}[/math], we see that [math]\tan x[/math] is positive when both functions [math]\cos x[/math] are positive, as they are for [math]0 \lt x \lt \frac{\pi}{2}[/math]; is zero when [math]\sin x = 0[/math], as it is for [math]x = 0[/math]; and is negative when the two functions have opposite sign, as they do for [math]-\frac{\pi}{2} \lt x \lt 0[/math]. We also see that [math]\tan x [/math] takes on arbitrarily large positive values as [math]x[/math] approaches [math]\frac{\pi}{2}[/math] from the left, since [math]\sin x[/math] approaches 1 and [math]\cos x[/math] approaches 0. Thus

The second derivative is given by

from which it follows that the graph is concave downward for [math]-\frac{\pi}{2} \lt x \lt 0[/math], concave upward for [math]0 \lt x \lt \frac{\pi}{2}[/math] and has a point of inflection at the origin. Combining all these facts with the few isolated values shown in Table 3, we obtain the graph shown in Figure 12.

| [math]x[/math] | [math]y[/math] = [math]\tan x[/math] | [math]\frac{dy}{dx} = \sec^{2}x[/math] |

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| [math]\frac{\pi}{6}[/math] | [math]\frac{1}{\sqrt 3}[/math] = 0.58 (approx.) | [math]\frac{4}{3}[/math] = 1.33 (approx.) |

| [math]\frac{\pi}{4}[/math] | 1 | 2 |

| [math]\frac{\pi}{3}[/math] | [math]\sqrt 3[/math] = 1.73 (approx.) | 4 |

The graph of [math]\cot x[/math] can be obtained in the same way in which we worked out the graph of [math]\tan x[/math]. However, there is a quicker way based on an identity. Since

we know that

The geometric significance of this identity is that the graph of [math]\cot x[/math] is obtained by translating (sliding) the graph of [math]\tan x[/math] to the left a distance [math]\frac{\pi}{2}[/math] and then reflecting about the [math]x[/math]-axis. From the definition, [math]\sec x = \frac{1}{\cos x}[/math], it is apparent that

If [math]a[/math] is any odd multiple of [math]\frac{\pi}{2}[/math], then [math]\cos a = 0[/math], and so

Moreover, on an interval where one function is increasing, its reciprocal function is decreasing, and vice versa. It follows that the over-all shape of the graph of [math]\sec x[/math] can be ascertained quite easily from the graph of its reciprocal function [math]\cos x[/math]. The graph of [math]\sec x[/math] is shown in Figure 13. The graph of [math]\csc x[/math] is related to that of [math]\sec x[/math] in the same way as the graph of [math]\sin x[/math] is related to the graph of [math]\cos x[/math].

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.