guide:Dba66870a5: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="d-none"><math> | |||

\newcommand{\ex}[1]{\item } | |||

\newcommand{\sx}{\item} | |||

\newcommand{\x}{\sx} | |||

\newcommand{\sxlab}[1]{} | |||

\newcommand{\xlab}{\sxlab} | |||

\newcommand{\prov}[1] {\quad #1} | |||

\newcommand{\provx}[1] {\quad \mbox{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\intext}[1]{\quad \mbox{#1} \quad} | |||

\newcommand{\R}{\mathrm{\bf R}} | |||

\newcommand{\Q}{\mathrm{\bf Q}} | |||

\newcommand{\Z}{\mathrm{\bf Z}} | |||

\newcommand{\C}{\mathrm{\bf C}} | |||

\newcommand{\dt}{\textbf} | |||

\newcommand{\goesto}{\rightarrow} | |||

\newcommand{\ddxof}[1]{\frac{d #1}{d x}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddx}{\frac{d}{dx}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddt}{\frac{d}{dt}} | |||

\newcommand{\dydx}{\ddxof y} | |||

\newcommand{\nxder}[3]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{d{#3}^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\deriv}[2]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{dx^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\dist}{\mathrm{distance}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccot}{\mathrm{arccot\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccsc}{\mathrm{arccsc\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsec}{\mathrm{arcsec\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arctanh}{\mathrm{arctanh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsinh}{\mathrm{arcsinh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccosh}{\mathrm{arccosh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\sech}{\mathrm{sech\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\csch}{\mathrm{csch\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\conj}[1]{\overline{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb} | |||

</math></div> | |||

In this section we shall use Riemann sums to derive several integral formulas for the volume of solids. The concept of volume is a familiar one, and we shall not give a mathematical definition of it. As a result, the | |||

formulas will be derived from properties of volume which seem intuitively natural and which we shall assume. By a solid we mean a subset of threedimensional space. | |||

A subset <math>Q</math> of three-dimensional space is said to be \textbf{bounded} if there exists a real number <math>k</math> such that, for any two points <math>p</math> and <math>q</math> in <math>Q</math>, the straightline distance in space between <math>p</math> and <math>q</math> is less than <math>k</math>. Alternatively, <math>Q</math> is bounded if and only if there exists a sphere in space which contains <math>Q</math> in its interior. In finding volumes of solids, we shall restrict ourselves to bounded subsets of three-dimensional space. | |||

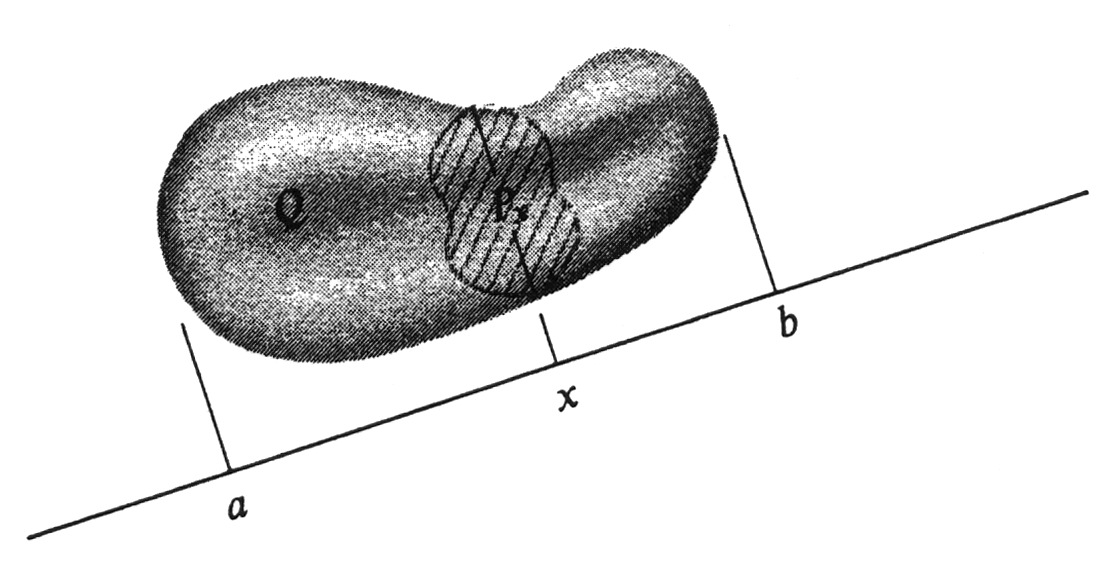

Let <math>Q</math> be a bounded solid, such as the one shown in Figure 11. We choose an arbitrary straight line in space for a coordinate axis. Any point | |||

on the line may be chosen for the origin and either direction as the direction of increasing numbers. The scale on the line must agree with the scale of distance in space. That is, if two points on the line correspond to the numbers <math>x</math> and <math>y</math>, then <math>|x - y|</math> must equal the straight-line distance in space between the two points. | |||

<div id="fig 8.11" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig8_11.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

For every number <math>x</math>, let <math>P_x</math> be the plane figure which is the intersection of the solid <math>Q</math> and the plane perpendicular to the coordinate axis at <math>x</math> (see Figure 11). The second assumption we make about <math>Q</math> is that every set <math>P_x</math> has a well-defined area. We then define a '''cross-sectional area function''' <math>A</math> by setting | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

A(x)= area(P_x). | |||

</math> | |||

One consequence of the fact that <math>Q</math> is bounded is that there exists an interval <math>[a, b]</math> such that, for every <math>x</math> outside of <math>[a, b]</math>, the set <math>P_x</math> is empty and so <math>A(x)= 0</math>. Another consequence is that the function <math>A</math> is bounded on <math>[a, b]</math>. | |||

Let us now consider a partition <math> \sigma = \{ x_0, ..., x_n \}</math> of the interval <math>[a, b]</math> which satisfies the inequalities | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

a = x_0 \leq x_1 \leq \cdots \leq x_n = b . | |||

</math> | |||

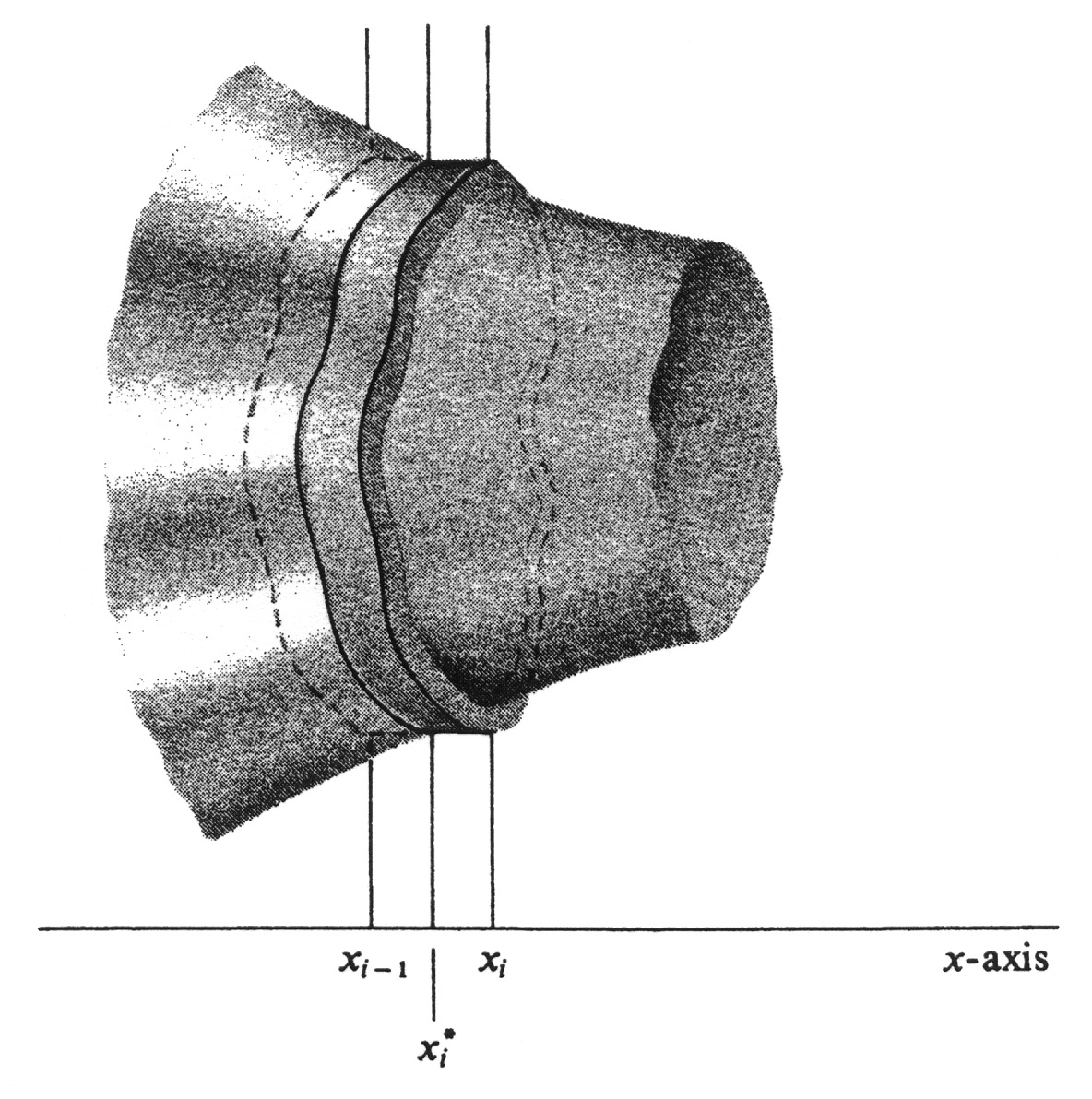

In each subinterval <math>[x_{i-1}, x_i]</math>, we choose an arbitrary number <math>x_i^*</math>. The product <math>A(x_i^*)(x_i - x_{i-1})</math> is equal to the volume of a right cylindrical slab with constant cross-sectional area <math>A(x_i^*)</math> and thickness <math>x_i - x_{i-1}</math>. If <math>x_i - x_{i-1}</math> is small, then we should expect <math>A(x_i^*)(x_i - x_{i-1})</math> to be a good approximation to the volume of the slice of <math>Q</math> which lies between the parallel planes at <math>x_{i-1}</math> and <math>x_i</math> (see Figure 12). Hence if the mesh of the partition <math>\sigma</math> is small, then the Riemann sum | |||

<div id="fig 8.12" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig8_12.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\sum_{i=1}^n A(x_i^*)(x_i - x_{i-1}) | |||

</math> | |||

will be a good approximation to the volume of <math>Q</math>. Moreover, the smaller the mesh, the better the approximation ought to be. Therefore, we shall assume that if the volume of <math>Q</math> is defined, then it is given by | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

vol(Q) = \lim_{|| \sigma || \rightarrow 0} \sum_{i=1}^n A(x_i^*)(x_i - x_{i-1}). | |||

</math> | |||

It follows immediately from the integrability criterion, Theorem (2.1), page 414, that | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-1| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

vol(Q) = \int_a^b A(x)dx. | |||

</math>|}} | |||

This is a basic integral formula for volume. | |||

<div id="fig 8.13" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig8_13.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

'''Example''' | |||

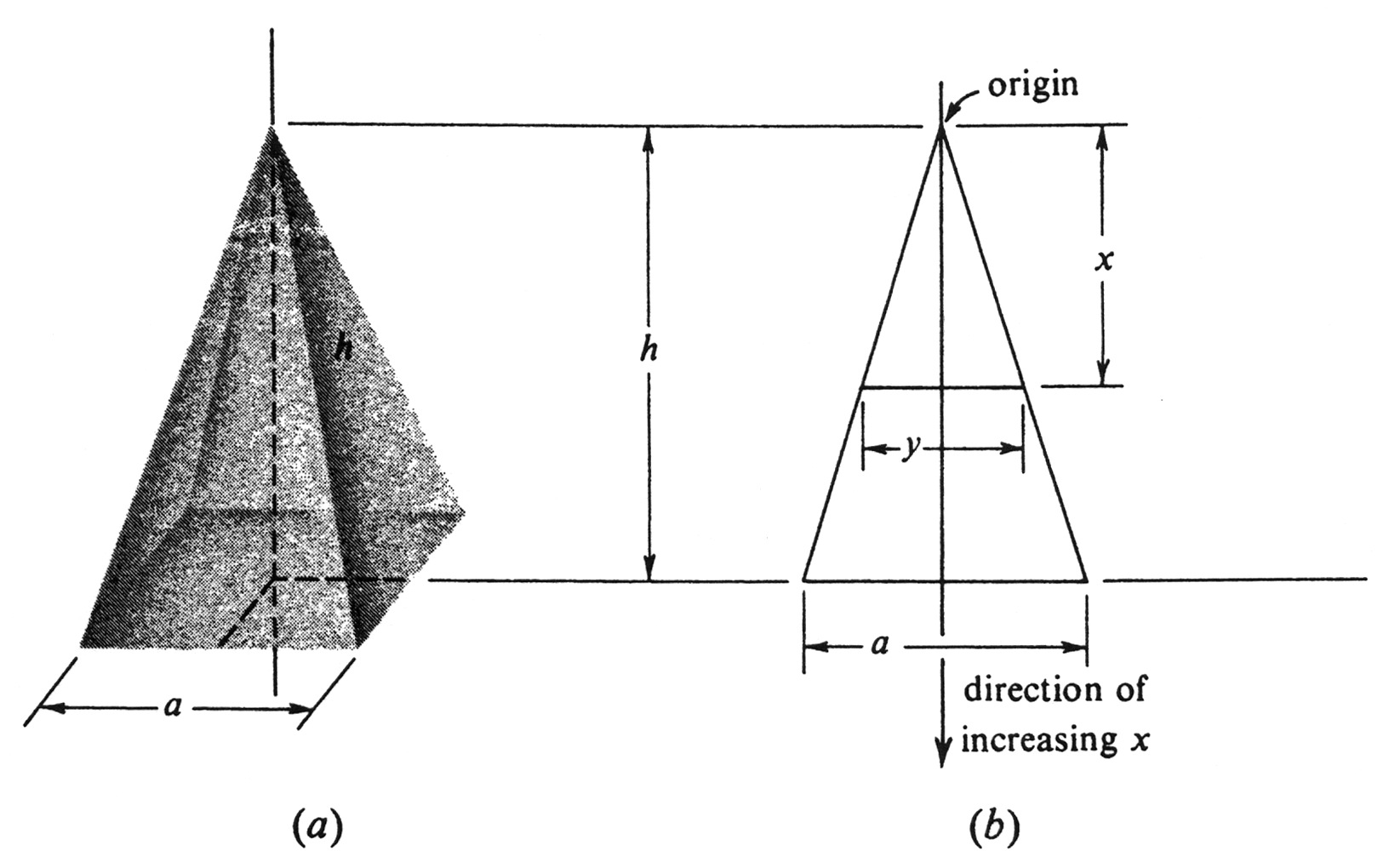

Find the volume <math>V</math> of a pyramid of height <math>h</math> with a square base of length <math>a</math> on a side. The pyramid is shown in Figure 13(a). We choose a vertical <math>x</math>-axis with origin at the apex and which cuts the center of the base at <math>x = h</math>. The cross-sectional area <math>A(x)</math> of the intersection of the pyramid and the plane perpendicular to the coordinate axis at <math>x</math> is easily seen from the side view [Figure 13(b)]. Since corresponding parts of similar triangles are proportional, it follows that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\frac{y}{ x} = \frac{a}{h} . | |||

</math> | |||

Hence | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

A(x) = y^2 = \frac{a^2 x^2}{h^2}, | |||

</math> | |||

and so | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

V &=& \int_0^h A(x) dx = \frac{a^2}{h^2} \int_0^h x^2 dx \\ | |||

&=& \frac{a^2}{h^2} \frac{h^3}{3} = \frac{1}{3} a^2h . | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

This is the well-known result that the volume of a pyramid is equal to one third the product of the height and the area of the base. | |||

<span id="fig 8.14"/> | |||

'''Example''' | |||

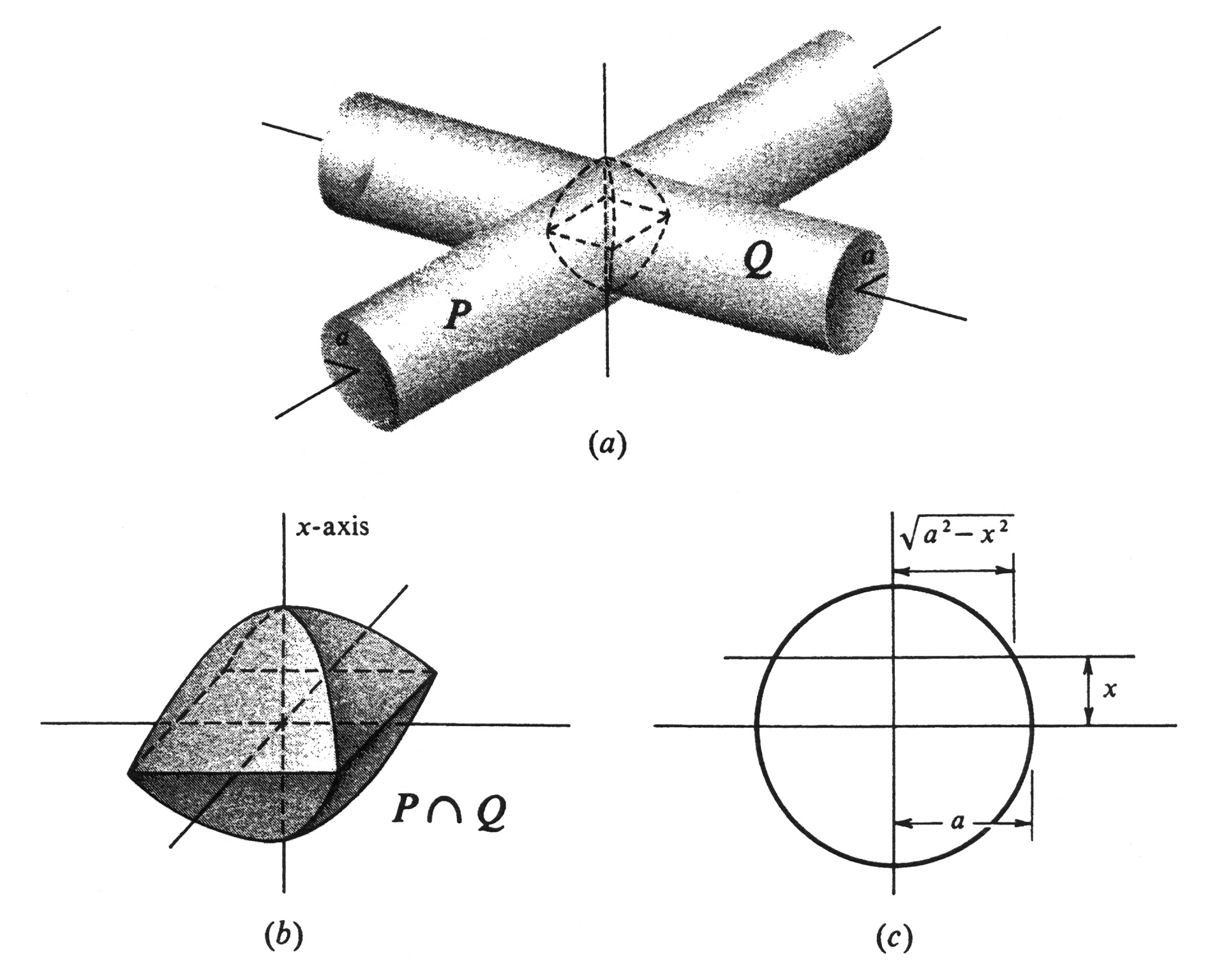

The axes of two right circular cylinders <math>P</math> and <math>Q</math> of equal radii <math>a</math> intersect at right angles as shown in Figure 14(a). Find the volume of the intersection <math>P \cap Q</math>. We choose an <math>x</math>-axis perpendicular to the axes of both cylinders and which passes through their point of intersection. This point is chosen for the origin, and the direction of increasing <math>x</math> is upward. | |||

Figure 14(b) helps one to see that the cross sections of <math>P \cap Q</math> perpendicular to the <math>x</math>-axis are squares. From the end-on view in Figure 14(c), it is apparent that the cross section at <math>x</math> is a square with an edge of length <math>2\sqrt {a^2 - x^2}</math>. Hence | |||

<div id="fig 8.14" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig8_14.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

A(x) = (2\sqrt{a^2 - x^2})^2 = 4(a^2 - x^2), \;\;\; -a \leq x \leq a. | |||

</math> | |||

By the integral formula for volume, therefore, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

vol(P \cap Q) = \int_{-a}^a A(x) dx = 4\int_{-a}^a (a^2 - x^2) dx. | |||

</math> | |||

Since <math>a^2 - x^2</math> is an even function, the integral from <math>-a</math> to <math>a</math> is twice the integral from 0 to <math>a</math>. Thus | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

vol(P \cap Q) &=& 8 \int_0^a (a^2 - x^2) dx\\ | |||

&=& 8 (a^2x - \frac{x^3}{3} )\big|_0^a = 8 (a^3 - \frac{a^3}{3}) \\ | |||

&=& \frac{16a^3}{3} . | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

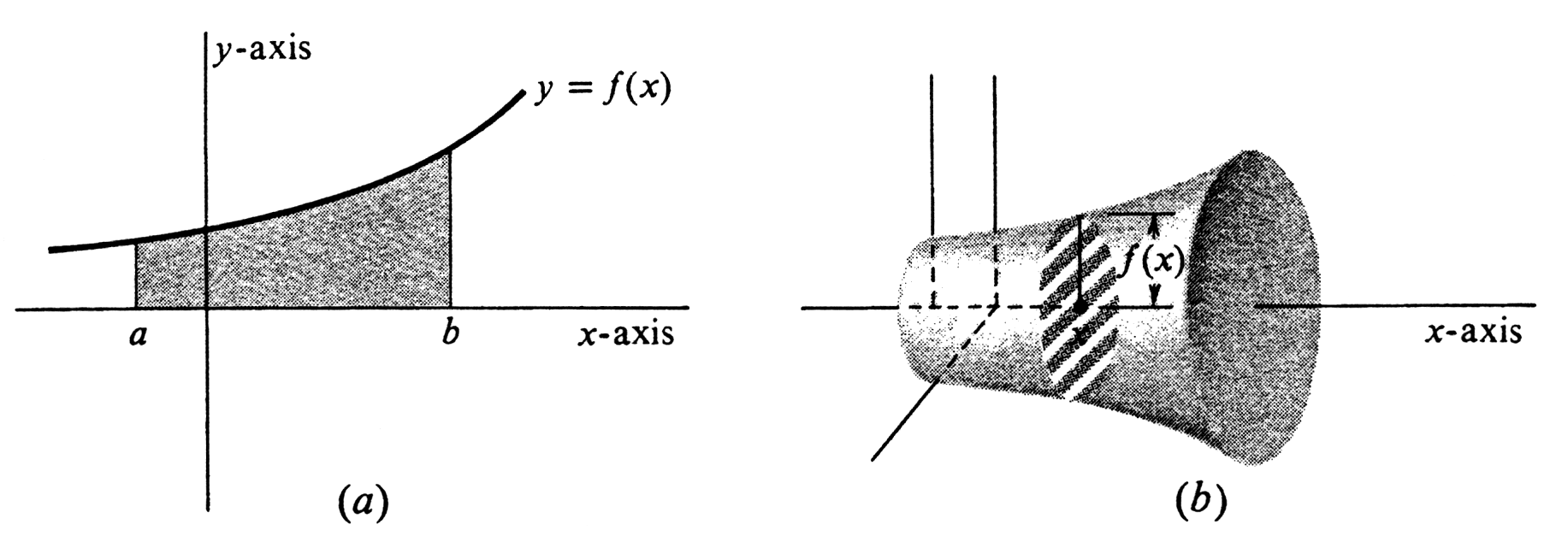

Consider a plane in three-dimensional space containing a region <math>R</math> and a line <math>L</math>. The solid generated by rotating <math>R</math> in space about <math>L</math> is called a '''solid of revolution.''' Among the solids of revolution are those described by rotating a portion of the graph of a function in the <math>xy</math>-plane about the <math>x</math>-axis (or the <math>y</math>-axis). We shall give an integral formula for the volumes of these solids, which is a special case of (4.1). Let <math>f</math> be a function integrable over the closed interval <math>[a, b]</math>, and consider the solid of revolution <math>Q</math> swept out by rotating about the <math>x</math>-axis the region bounded by the graph of <math>f</math>, the <math>x</math>-axis, and the <math>y</math>-axis lines <math>x = a</math> and <math>x = b</math>. Such a region is illustrated in Figure 15(a), and the corresponding solid in Figure 15(b). For every <math>x</math> in <math>[a, b]</math>, the cross section of <math>Q</math> perpendicular to the <math>x</math>-axis at <math>x</math> is a circular disk, of radius <math>|f(x)|</math>. Hence | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

A(x)= \pi | f(x) |^2= \pi [f(x)]^2. | |||

</math> | |||

By formula (4.1), therefore, the volume of the solid of revolution <math>Q</math> is given by | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-2| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

vol(Q) = \pi \int_a^b [f(x)]^2 dx. | |||

</math>|}} | |||

<div id="fig 8.15" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig8_15.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

'''Example''' | |||

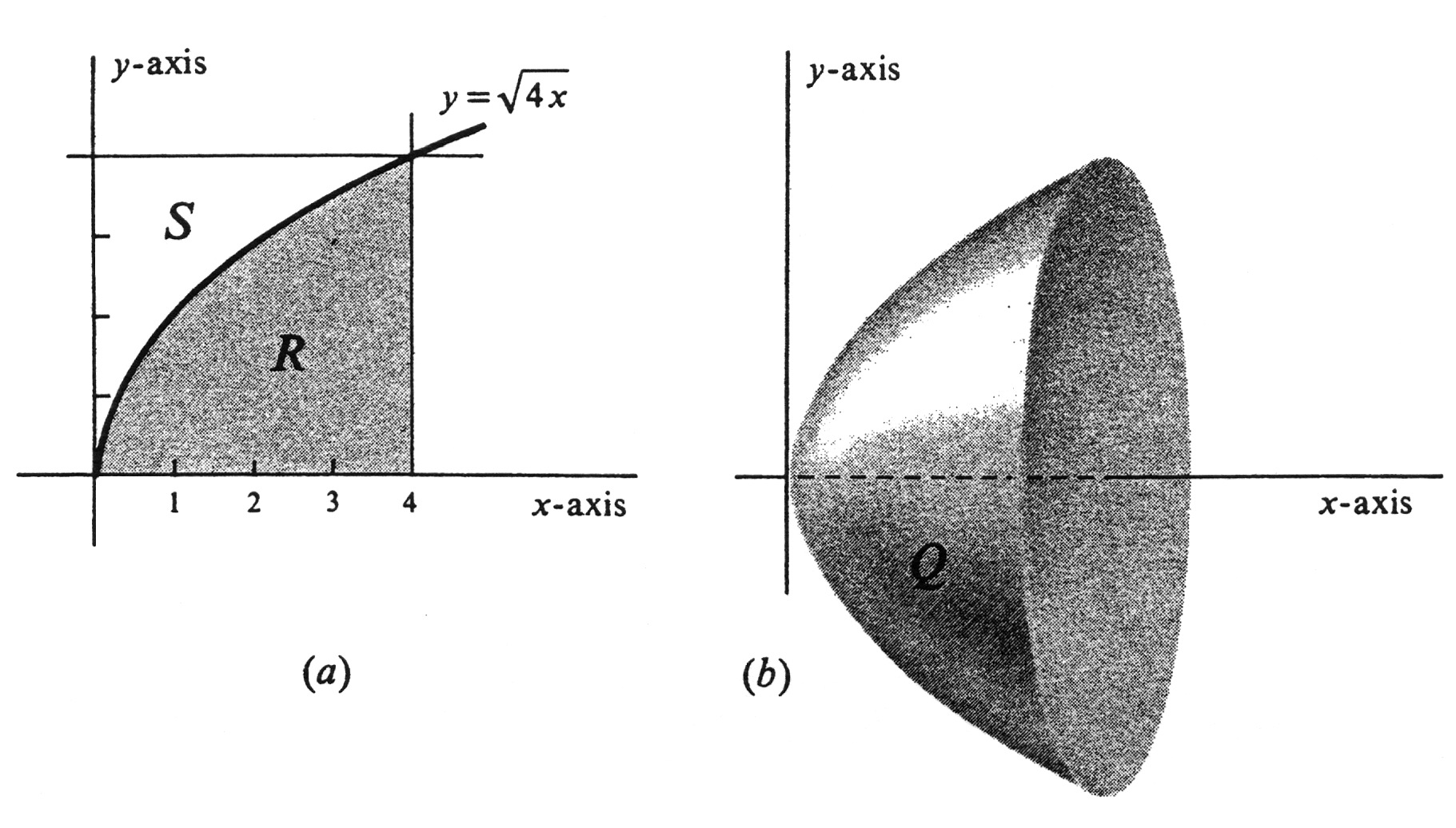

Let <math>R</math> be the region in the upper half-plane bounded by the parabola <math>y^2 = 4x</math>, the x-axis, and the line <math>x = 4</math>. Find the volume of <math>Q</math>, the solid of revolution obtained by rotating this region about the <math>x</math>-axis. The region and the solid are drawn in Figure 16. That part of the parabola in the upper half-plane is the set of all points <math>(x, y)</math> such that <math>y^2 = 4x</math> and <math>y \geq 0</math>. This set is the graph of the equation <math>y= \sqrt {4x}</math>, and we therefore take <math>f(x) = \sqrt {4x}</math> in formula (4.2), obtaining | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

vol(Q) &=& \pi \int_0^4 [f(x)]^2 dx = \pi \int_0^4 4xdx \\ | |||

&=& 4\pi \frac{x^2}{2} \big|_0^4 = 32\pi . | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

<div id="fig 8.16" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig8_16.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

<span id="fig 8.17"/> | |||

'''Example''' | |||

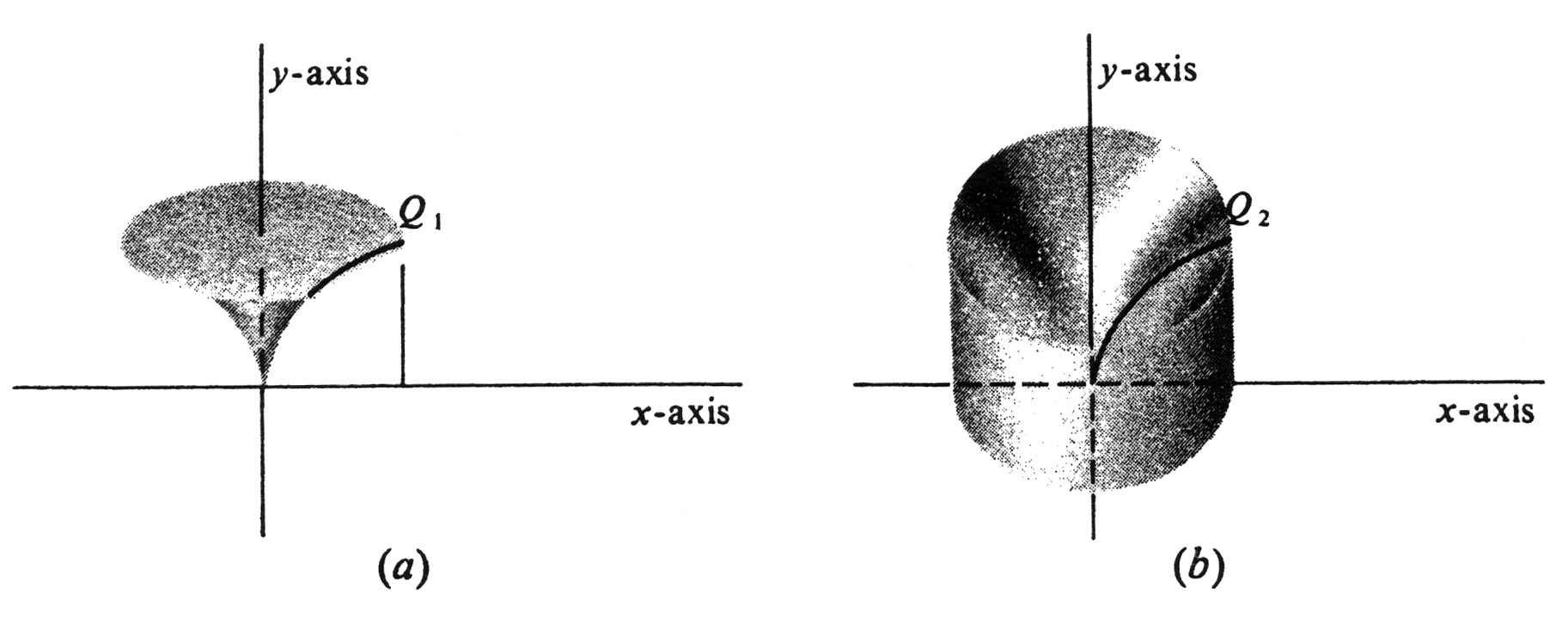

Let <math>R</math> be the region in Example 3, and let <math>S</math> be the region bounded by the parabola <math>y^2 = 4x</math>, the <math>y</math>-axis, and the line <math>y = 4</math>. Both regions are shown in Figure 16(a). Find the volumes of the two solids of revolution <math>Q_1</math> and <math>Q_2</math>, obtained by rotating <math>S</math> and <math>R</math>, respectively, about the <math>y</math>-axis. The two solids are illustrated in Figure 17. The easiest way to find the volume of <math>Q_1</math> is to use the counterpart of formula (4.2) for functions of <math>y</math>. The equation <math>y^2 = 4x</math> is equivalent to the equation <math>x = \frac{y^2}{4}</math>, and the parabola is therefore the graph of the function of <math>y</math> defined by <math>f(y) = \frac{y^2}{4}</math> . By symmetry therefore, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

vol(Q_1) &=& \pi \int_0^4 [f(y)]^2 dy = \pi \int_0^4 \frac{y^4}{16} dy \\ | |||

&=& \frac{\pi}{16} \frac{y^5}{5} \big|_0^4 = \frac{64 \pi}{5} . | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

<div id="fig 8.17" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig8_17.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

The union of <math>Q_1</math> and <math>Q_2</math> is a right circular cylinder of radius 4 and height 4. Hence | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

vol(Q_1 \cup Q_2) = (\pi 4^2) \cdot 4 = 64 \pi. | |||

</math> | |||

It is obvious that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

vol(Q_1 \cup Q_2) = vol(Q_1) + vol(Q_2). | |||

</math> | |||

Hence | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

vol(Q_2) &=& vol(Q_1 \cup Q_2) - vol(Q_1) \\ | |||

&=& 64 \pi - \frac{64\pi}{5} = \frac{256 \pi}{5} . | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

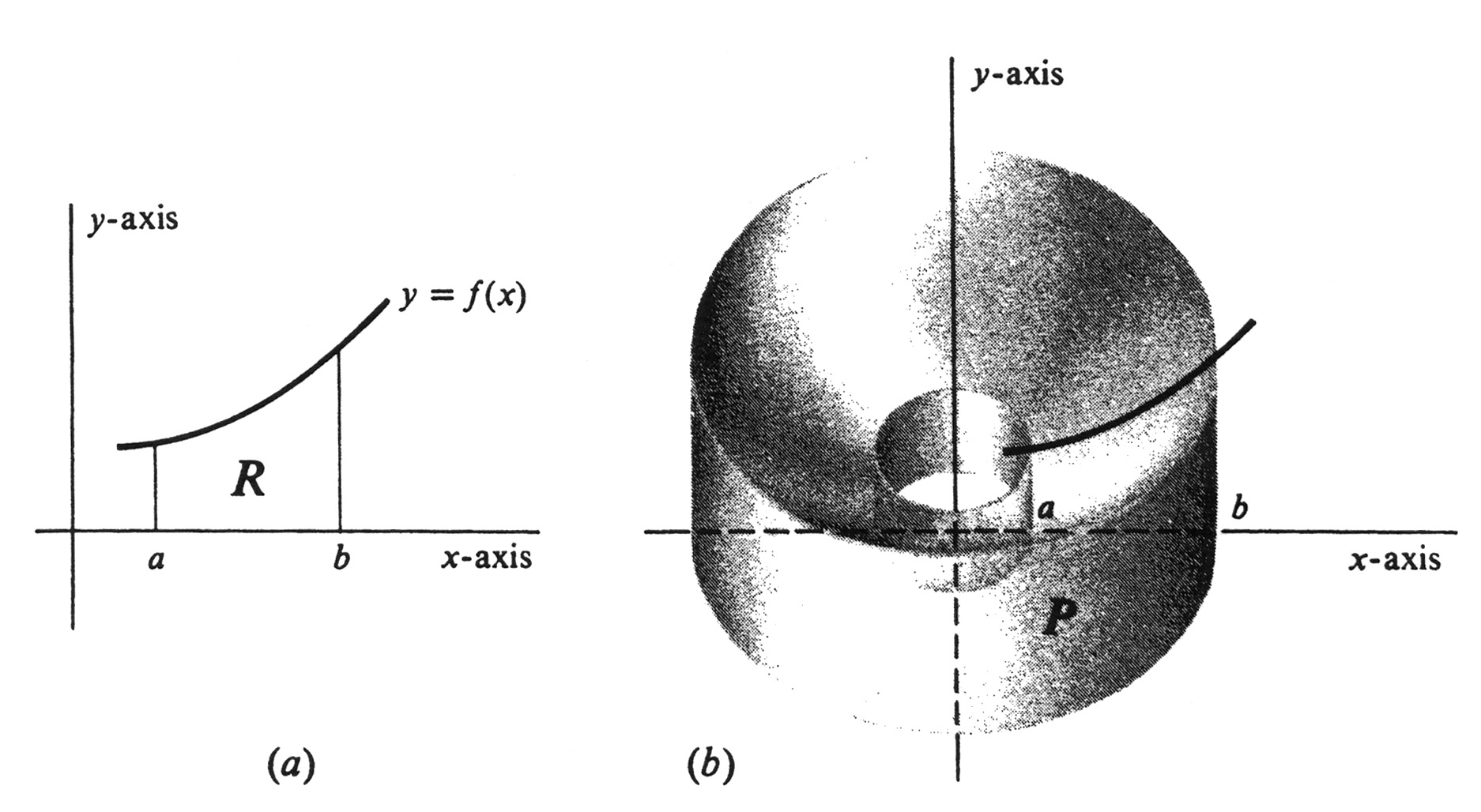

Another way of computing the volumes of certain solids of revolution is the method of '''cylindrical shells.''' It may be used, for example, to find the volume of the solid <math>Q_2</math> in Figure 17(b) directly, and it constitutes another interesting application of the integral as a limit of Riemann sums. Let <math>f</math> be a function which is nonnegative and continuous at every point of a closed interval <math>[a, b]</math>, where <math>a \geq 0</math>. Let <math>R</math> be the region bounded by the graph of <math>f</math>, the <math>x</math>-axis, and the lines <math>x = a</math> and <math>x = b</math>. We shall derive a formula for the volume of <math>P</math>, the solid of revolution obtained by revolving the region <math>R</math> about the <math>y</math>-axis (see Figure 18). | |||

<div id="fig 8.18" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig8_18.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

<div id="fig 8.19" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig8_19.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

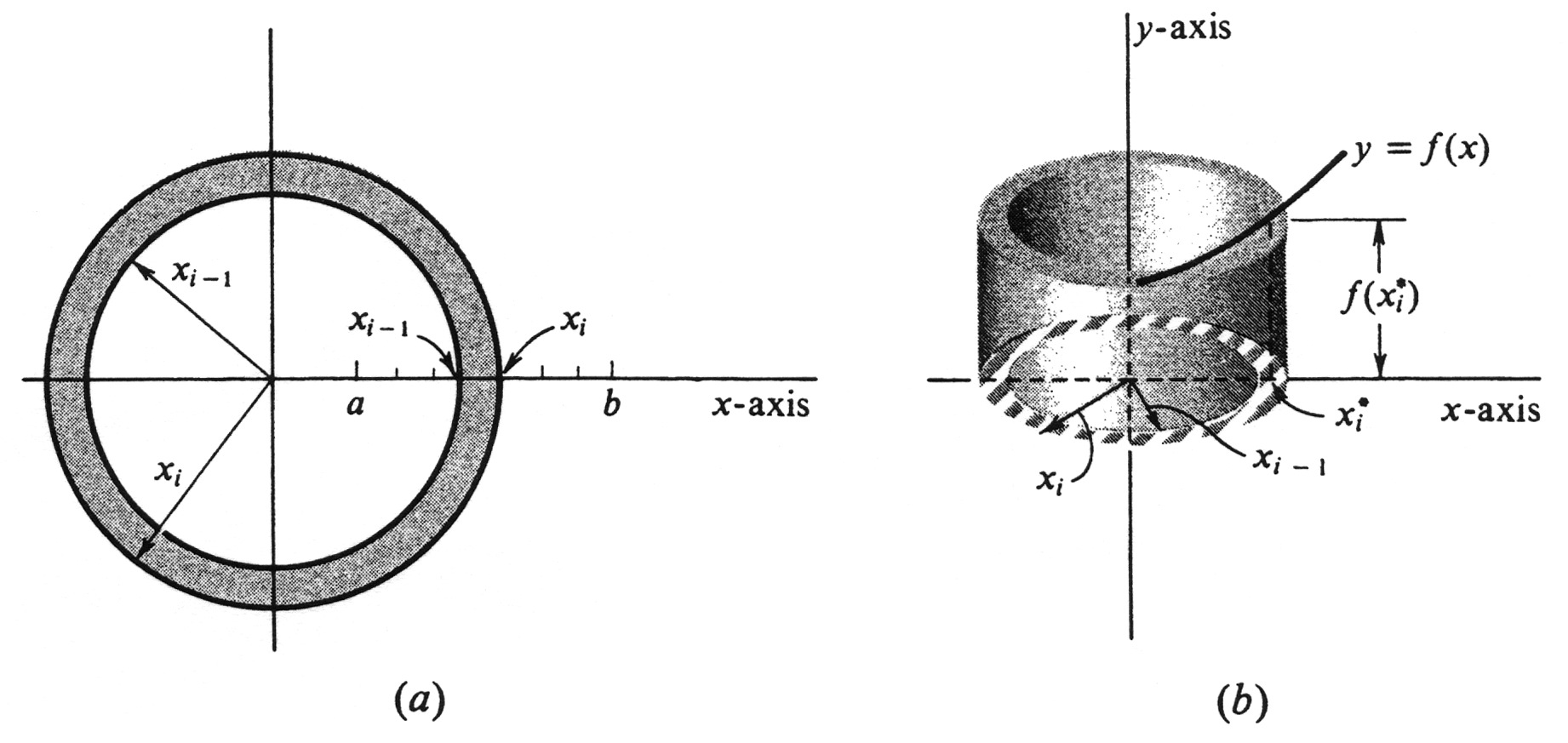

Consider a partition <math>\sigma = \{x_0, ..., x_n \}</math> of the interval <math>[a, b]</math> such that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

a = x_0 \leq x_1 \leq \cdots \leq x_n = b, | |||

</math> | |||

and choose numbers <math>x_i^*,..., x_n^*</math> such that <math>x_{i-1} \leq x_i^* \leq x_i</math> for each <math>i = 1, ... , n</math>. Then <math>\pi (x_i^2 -x_{i-1}^2)</math> is the area of the shaded annulus shown | |||

in Figure 19(a), and <math>\pi f(x_i^*)(x_i^2 - x_{i-1}^2)</math> is the volume of the cylindrical shell of height <math>f(x_i^*)</math> and thickness <math>x_i - x_{i-1}</math> shown in Figure 19(b). The essential idea in the derivation is that, if <math>x_i - x_{i-1}</math> is small, then the volume of this shell should be a good approximation to the volume of that part of the solid <math>P</math> that lies between the two cylinders of radii <math>x_{i-1}</math> and <math>x_i</math>. Hence if the mesh of the partition <math>\sigma</math> is small, then the sum of the volumes of the shells, i.e., the sum | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\sum_{i=1}^n \pi f (x_i^*)(x_i^2 - x_{i-1}^2), | |||

</math> | |||

should be a good approximation to the volume of <math>P</math>. Specifically, we shall assume that | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq8.4.1"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

vol(P) = \lim_{||\sigma|| \rightarrow 0} \sum_{i = 1}^n \pi f(x_i^*)(x_i^2 - x_{i-1}^2). | |||

\label{eq8.4.1} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

On the basis of this assumption we now prove the theorem | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-3| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

vol(P) = 2 \pi \int_a^b x f(x) dx. | |||

</math> | |||

|Since each <math>x_i^*</math> may be any number in the subinterval <math>[x_{i-1}, x_i]</math>, let us for convenience choose it to be the midpoint. This means that <math>x_i^* = \frac{x_i + x_{i-1}}{2}</math> or, equivalently, that <math>x_i + x_{i-1} = 2x_i^*</math>. Hence | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

x_i^2 - x_{i - 1}^2 &=& (x_i + x_{i - 1})(x_i - x_{i - 1})\\ | |||

&=& 2x_i^*(x_i - x_{i-1}), | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

and it follows that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\sum_{i=1}^n \pi f (x_i^*)(x_i^2 - x_{i-1}^2) = \sum_{i=1}^n 2\pi x_i^* f(x_i^*)(x_i - x_{i-1}) . | |||

</math> | |||

By our assumption (1), the left side of this equation approaches <math>vol(P)</math> as a limit as the mesh <math>|| \sigma ||</math> approaches zero. The right side is a Riemann sum for the continuous function <math>2\pi xf(x)</math> and therefore approaches the integral <math>\int_a^b 2\pi xf(x) dx</math> as a limit as <math>|| \sigma ||</math> all approaches zero. This completes the proof.}} | |||

The region <math>R</math> in Figure 16(a), when rotated about the <math>y</math>-axis, generates the solid of revolution <math>Q_2</math> illustrated in Figure 17(b). Let us compute the volume of <math>Q_2</math> by the method of cylindrical shells. The function <math>f</math> in the formula is in this case the one defined by <math>f(x) = \sqrt{4x} = 2x^{1/2}</math>. In addition, <math>a = 0</math> and <math>b = 4</math>. We therefore obtain | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

vol(Q_2) &=& 2\pi \int_0^4 x 2x^{1/2} dx \\ | |||

&=& 4\pi \int_0^4 x^{3/2} dx = 4 \pi \cdot \frac{2}{5} \cdot x^{5/2} \big|_0^4 \\ | |||

&=& 4 \pi \cdot \frac{2}{5} \cdot 32 = \frac{256 \pi}{5} , | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

which agrees with the value obtained in Example 4. | |||

<div id="fig 8.20" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig8_20.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

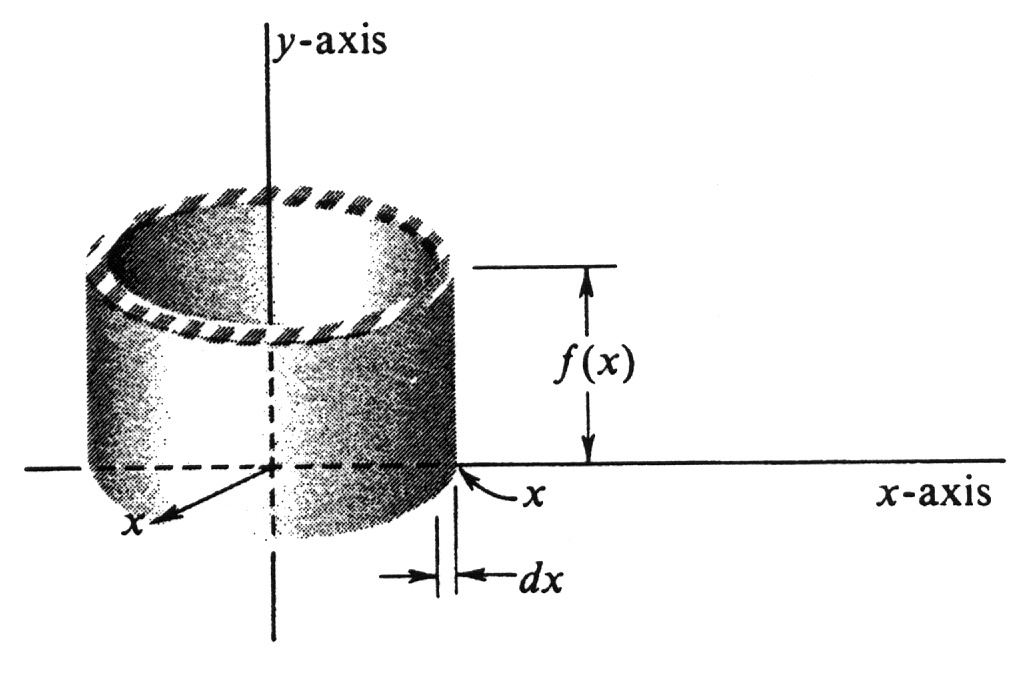

It was pointed out in Section 6 of Chapter 4 that the <math>dx</math> which appears in <math>\int f(x) dx</math> can be legitimately regarded as a differential. Moreover, it was remarked in Section 6 of Chapter 2 that the traditional attitude toward a differential is that it represents an infinitesimally small quantity. These ideas are a good aid to the imagination here, too. Thus, as the meshes of the subdivisions in the Riemann sums <math>\sum_{i=1}^n f(x_i^*)(x_i-x_{i-1})</math> become infinitesimally small, the differences <math>x_i - x_{i-1}</math> become <math>dx</math> and the summation | |||

<math>\sum</math> becomes the integral <math>\int</math>. Consider the following rough-and-ready derivation of the formula used in the method of cylindrical shells. We imagine a shell of infinitesimal thickness at each <math>x</math> in the interval <math>[a, b]</math>. The radius is <math>x</math>, the thickness <math>dx</math>, and the height <math>f(x)</math> (see Figure 20). The circumference of the shell is <math>2\pi x</math>, and the area of the edge is the product of the circumference and the thickness, <math>2\pi xdx</math>. Multiplying by the height, we get the infinitesimal volume <math>2\pi xf(x)dx</math>. The total volume is obtained by adding all the infinitesimal volumes. We get <math>\sum 2 \pi x f(x) dx</math> or, actually, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_a^b 2\pi x f (x) dx = 2\pi \int_a^b xf (x) dx | |||

</math> | |||

for the answer. | |||

The derivation of integral formulas by this process of “summing infinitesimals” is extremely useful both as a guide to memory and in helping one to discover the right formula in the first place. Of course, any such heuristic approach is just)fied mathematically only if it can be supplemented by careful analysis. | |||

==General references== | |||

{{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | |||

Latest revision as of 00:23, 20 November 2024

In this section we shall use Riemann sums to derive several integral formulas for the volume of solids. The concept of volume is a familiar one, and we shall not give a mathematical definition of it. As a result, the formulas will be derived from properties of volume which seem intuitively natural and which we shall assume. By a solid we mean a subset of threedimensional space. A subset [math]Q[/math] of three-dimensional space is said to be \textbf{bounded} if there exists a real number [math]k[/math] such that, for any two points [math]p[/math] and [math]q[/math] in [math]Q[/math], the straightline distance in space between [math]p[/math] and [math]q[/math] is less than [math]k[/math]. Alternatively, [math]Q[/math] is bounded if and only if there exists a sphere in space which contains [math]Q[/math] in its interior. In finding volumes of solids, we shall restrict ourselves to bounded subsets of three-dimensional space. Let [math]Q[/math] be a bounded solid, such as the one shown in Figure 11. We choose an arbitrary straight line in space for a coordinate axis. Any point on the line may be chosen for the origin and either direction as the direction of increasing numbers. The scale on the line must agree with the scale of distance in space. That is, if two points on the line correspond to the numbers [math]x[/math] and [math]y[/math], then [math]|x - y|[/math] must equal the straight-line distance in space between the two points.

For every number [math]x[/math], let [math]P_x[/math] be the plane figure which is the intersection of the solid [math]Q[/math] and the plane perpendicular to the coordinate axis at [math]x[/math] (see Figure 11). The second assumption we make about [math]Q[/math] is that every set [math]P_x[/math] has a well-defined area. We then define a cross-sectional area function [math]A[/math] by setting

One consequence of the fact that [math]Q[/math] is bounded is that there exists an interval [math][a, b][/math] such that, for every [math]x[/math] outside of [math][a, b][/math], the set [math]P_x[/math] is empty and so [math]A(x)= 0[/math]. Another consequence is that the function [math]A[/math] is bounded on [math][a, b][/math]. Let us now consider a partition [math] \sigma = \{ x_0, ..., x_n \}[/math] of the interval [math][a, b][/math] which satisfies the inequalities

In each subinterval [math][x_{i-1}, x_i][/math], we choose an arbitrary number [math]x_i^*[/math]. The product [math]A(x_i^*)(x_i - x_{i-1})[/math] is equal to the volume of a right cylindrical slab with constant cross-sectional area [math]A(x_i^*)[/math] and thickness [math]x_i - x_{i-1}[/math]. If [math]x_i - x_{i-1}[/math] is small, then we should expect [math]A(x_i^*)(x_i - x_{i-1})[/math] to be a good approximation to the volume of the slice of [math]Q[/math] which lies between the parallel planes at [math]x_{i-1}[/math] and [math]x_i[/math] (see Figure 12). Hence if the mesh of the partition [math]\sigma[/math] is small, then the Riemann sum

will be a good approximation to the volume of [math]Q[/math]. Moreover, the smaller the mesh, the better the approximation ought to be. Therefore, we shall assume that if the volume of [math]Q[/math] is defined, then it is given by

It follows immediately from the integrability criterion, Theorem (2.1), page 414, that

This is a basic integral formula for volume.

Example

Find the volume [math]V[/math] of a pyramid of height [math]h[/math] with a square base of length [math]a[/math] on a side. The pyramid is shown in Figure 13(a). We choose a vertical [math]x[/math]-axis with origin at the apex and which cuts the center of the base at [math]x = h[/math]. The cross-sectional area [math]A(x)[/math] of the intersection of the pyramid and the plane perpendicular to the coordinate axis at [math]x[/math] is easily seen from the side view [Figure 13(b)]. Since corresponding parts of similar triangles are proportional, it follows that

Hence

and so

This is the well-known result that the volume of a pyramid is equal to one third the product of the height and the area of the base.

Example

The axes of two right circular cylinders [math]P[/math] and [math]Q[/math] of equal radii [math]a[/math] intersect at right angles as shown in Figure 14(a). Find the volume of the intersection [math]P \cap Q[/math]. We choose an [math]x[/math]-axis perpendicular to the axes of both cylinders and which passes through their point of intersection. This point is chosen for the origin, and the direction of increasing [math]x[/math] is upward. Figure 14(b) helps one to see that the cross sections of [math]P \cap Q[/math] perpendicular to the [math]x[/math]-axis are squares. From the end-on view in Figure 14(c), it is apparent that the cross section at [math]x[/math] is a square with an edge of length [math]2\sqrt {a^2 - x^2}[/math]. Hence

By the integral formula for volume, therefore,

Since [math]a^2 - x^2[/math] is an even function, the integral from [math]-a[/math] to [math]a[/math] is twice the integral from 0 to [math]a[/math]. Thus

Consider a plane in three-dimensional space containing a region [math]R[/math] and a line [math]L[/math]. The solid generated by rotating [math]R[/math] in space about [math]L[/math] is called a solid of revolution. Among the solids of revolution are those described by rotating a portion of the graph of a function in the [math]xy[/math]-plane about the [math]x[/math]-axis (or the [math]y[/math]-axis). We shall give an integral formula for the volumes of these solids, which is a special case of (4.1). Let [math]f[/math] be a function integrable over the closed interval [math][a, b][/math], and consider the solid of revolution [math]Q[/math] swept out by rotating about the [math]x[/math]-axis the region bounded by the graph of [math]f[/math], the [math]x[/math]-axis, and the [math]y[/math]-axis lines [math]x = a[/math] and [math]x = b[/math]. Such a region is illustrated in Figure 15(a), and the corresponding solid in Figure 15(b). For every [math]x[/math] in [math][a, b][/math], the cross section of [math]Q[/math] perpendicular to the [math]x[/math]-axis at [math]x[/math] is a circular disk, of radius [math]|f(x)|[/math]. Hence

By formula (4.1), therefore, the volume of the solid of revolution [math]Q[/math] is given by

Example

Let [math]R[/math] be the region in the upper half-plane bounded by the parabola [math]y^2 = 4x[/math], the x-axis, and the line [math]x = 4[/math]. Find the volume of [math]Q[/math], the solid of revolution obtained by rotating this region about the [math]x[/math]-axis. The region and the solid are drawn in Figure 16. That part of the parabola in the upper half-plane is the set of all points [math](x, y)[/math] such that [math]y^2 = 4x[/math] and [math]y \geq 0[/math]. This set is the graph of the equation [math]y= \sqrt {4x}[/math], and we therefore take [math]f(x) = \sqrt {4x}[/math] in formula (4.2), obtaining

Example

Let [math]R[/math] be the region in Example 3, and let [math]S[/math] be the region bounded by the parabola [math]y^2 = 4x[/math], the [math]y[/math]-axis, and the line [math]y = 4[/math]. Both regions are shown in Figure 16(a). Find the volumes of the two solids of revolution [math]Q_1[/math] and [math]Q_2[/math], obtained by rotating [math]S[/math] and [math]R[/math], respectively, about the [math]y[/math]-axis. The two solids are illustrated in Figure 17. The easiest way to find the volume of [math]Q_1[/math] is to use the counterpart of formula (4.2) for functions of [math]y[/math]. The equation [math]y^2 = 4x[/math] is equivalent to the equation [math]x = \frac{y^2}{4}[/math], and the parabola is therefore the graph of the function of [math]y[/math] defined by [math]f(y) = \frac{y^2}{4}[/math] . By symmetry therefore,

The union of [math]Q_1[/math] and [math]Q_2[/math] is a right circular cylinder of radius 4 and height 4. Hence

It is obvious that

Hence

Another way of computing the volumes of certain solids of revolution is the method of cylindrical shells. It may be used, for example, to find the volume of the solid [math]Q_2[/math] in Figure 17(b) directly, and it constitutes another interesting application of the integral as a limit of Riemann sums. Let [math]f[/math] be a function which is nonnegative and continuous at every point of a closed interval [math][a, b][/math], where [math]a \geq 0[/math]. Let [math]R[/math] be the region bounded by the graph of [math]f[/math], the [math]x[/math]-axis, and the lines [math]x = a[/math] and [math]x = b[/math]. We shall derive a formula for the volume of [math]P[/math], the solid of revolution obtained by revolving the region [math]R[/math] about the [math]y[/math]-axis (see Figure 18).

Consider a partition [math]\sigma = \{x_0, ..., x_n \}[/math] of the interval [math][a, b][/math] such that

and choose numbers [math]x_i^*,..., x_n^*[/math] such that [math]x_{i-1} \leq x_i^* \leq x_i[/math] for each [math]i = 1, ... , n[/math]. Then [math]\pi (x_i^2 -x_{i-1}^2)[/math] is the area of the shaded annulus shown in Figure 19(a), and [math]\pi f(x_i^*)(x_i^2 - x_{i-1}^2)[/math] is the volume of the cylindrical shell of height [math]f(x_i^*)[/math] and thickness [math]x_i - x_{i-1}[/math] shown in Figure 19(b). The essential idea in the derivation is that, if [math]x_i - x_{i-1}[/math] is small, then the volume of this shell should be a good approximation to the volume of that part of the solid [math]P[/math] that lies between the two cylinders of radii [math]x_{i-1}[/math] and [math]x_i[/math]. Hence if the mesh of the partition [math]\sigma[/math] is small, then the sum of the volumes of the shells, i.e., the sum

should be a good approximation to the volume of [math]P[/math]. Specifically, we shall assume that

On the basis of this assumption we now prove the theorem

Since each [math]x_i^*[/math] may be any number in the subinterval [math][x_{i-1}, x_i][/math], let us for convenience choose it to be the midpoint. This means that [math]x_i^* = \frac{x_i + x_{i-1}}{2}[/math] or, equivalently, that [math]x_i + x_{i-1} = 2x_i^*[/math]. Hence

The region [math]R[/math] in Figure 16(a), when rotated about the [math]y[/math]-axis, generates the solid of revolution [math]Q_2[/math] illustrated in Figure 17(b). Let us compute the volume of [math]Q_2[/math] by the method of cylindrical shells. The function [math]f[/math] in the formula is in this case the one defined by [math]f(x) = \sqrt{4x} = 2x^{1/2}[/math]. In addition, [math]a = 0[/math] and [math]b = 4[/math]. We therefore obtain

which agrees with the value obtained in Example 4.

It was pointed out in Section 6 of Chapter 4 that the [math]dx[/math] which appears in [math]\int f(x) dx[/math] can be legitimately regarded as a differential. Moreover, it was remarked in Section 6 of Chapter 2 that the traditional attitude toward a differential is that it represents an infinitesimally small quantity. These ideas are a good aid to the imagination here, too. Thus, as the meshes of the subdivisions in the Riemann sums [math]\sum_{i=1}^n f(x_i^*)(x_i-x_{i-1})[/math] become infinitesimally small, the differences [math]x_i - x_{i-1}[/math] become [math]dx[/math] and the summation [math]\sum[/math] becomes the integral [math]\int[/math]. Consider the following rough-and-ready derivation of the formula used in the method of cylindrical shells. We imagine a shell of infinitesimal thickness at each [math]x[/math] in the interval [math][a, b][/math]. The radius is [math]x[/math], the thickness [math]dx[/math], and the height [math]f(x)[/math] (see Figure 20). The circumference of the shell is [math]2\pi x[/math], and the area of the edge is the product of the circumference and the thickness, [math]2\pi xdx[/math]. Multiplying by the height, we get the infinitesimal volume [math]2\pi xf(x)dx[/math]. The total volume is obtained by adding all the infinitesimal volumes. We get [math]\sum 2 \pi x f(x) dx[/math] or, actually,

for the answer. The derivation of integral formulas by this process of “summing infinitesimals” is extremely useful both as a guide to memory and in helping one to discover the right formula in the first place. Of course, any such heuristic approach is just)fied mathematically only if it can be supplemented by careful analysis.

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.