guide:D1cdd1f26e: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

\newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb} | \newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb} | ||

</math></div> | </math></div> | ||

The theory of convergence of infinite series is in many respects simpler for those series which do not contain both positive and negative terms. A series which contains no negative terms is called '''nonnegative'''. Thus <math>\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i</math> is nonnegative if and only if <math>a_i \geq 0</math> for every integer <math>i \geq m</math>. In this section we shall study two convergence criteria for such series: The Integral Test and the Comparison Test. | The theory of convergence of infinite series is in many respects simpler for those series which do not contain both positive and negative terms. A series which contains no negative terms is called '''nonnegative'''. Thus <math>\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i</math> is nonnegative if and only if <math>a_i \geq 0</math> for every integer <math>i \geq m</math>. In this section we shall study two convergence criteria for such series: The Integral Test and the Comparison Test. | ||

Let <math>\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i</math> be an arbitrary infinite series (not necessarily nonnegative), and let <math>\{ s_n \}</math> be the corresponding sequence of partial sums. We recall that <math>s_n = \sum_{i=m}^n a_i</math>, for every integer <math>n \geq m</math>, and that, if <math>\{ s_n \}</math> converges, then <math>\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_n</math>. We shall extend the convention regarding the symbol <math>\infty</math> and write | Let <math>\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i</math> be an arbitrary infinite series (not necessarily nonnegative), and let <math>\{ s_n \}</math> be the corresponding sequence of partial sums. We recall that <math>s_n = \sum_{i=m}^n a_i</math>, for every integer <math>n \geq m</math>, and that, if <math>\{ s_n \}</math> converges, then <math>\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_n</math>. We shall extend the convention regarding the symbol <math>\infty</math> and write | ||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

is convergent if and only if the improper integral <math>\int_m^\infty f(x) dx</math> is convergent. | is convergent if and only if the improper integral <math>\int_m^\infty f(x) dx</math> is convergent. | ||

<div id="fig 9.4" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | <div id{{=}}"fig 9.4" class{{=}}"d-flex justify-content-center"> | ||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig9_4.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | [[File:guide_c5467_scanfig9_4.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

The integral is therefore bounded above, and it follows that <math>\lim_{b \rightarrow \infty} \int_m^b f(x) dx</math> exists [see (1.4'), page 480]. Hence <math>\int_m^\infty f(x) dx</math> is a convergent improper integral, and the proof of the Integral Test is complete.}} | The integral is therefore bounded above, and it follows that <math>\lim_{b \rightarrow \infty} \int_m^b f(x) dx</math> exists [see (1.4'), page 480]. Hence <math>\int_m^\infty f(x) dx</math> is a convergent improper integral, and the proof of the Integral Test is complete.}} | ||

The convergence or divergence of many infinite series can be determined easily by the Integral Test. Important among these are series of the form | The convergence or divergence of many infinite series can be determined easily by the Integral Test. Important among these are series of the form | ||

| Line 126: | Line 127: | ||

\sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{i^p} = 1 + \frac{1}{2^p} + \frac{1}{3^p} + \cdots , | \sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{i^p} = 1 + \frac{1}{2^p} + \frac{1}{3^p} + \cdots , | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

where <math>p</math> is a positive real number. Such a series is called a ''' | where <math>p</math> is a positive real number. Such a series is called a '''<math>p</math>-series.''' An example is the divergent harmonic series, for which <math>p = 1</math>. The basic convergence theorem is | ||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-5|The <math>p</math>-series <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{i^p}</math> converges if and only if <math>p > 1</math>. | {{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-5|The <math>p</math>-series <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{i^p}</math> converges if and only if <math>p > 1</math>. | ||

|The function <math>f</math> defined by <math>f(x) = \frac{1}{x^p}</math> is nonnegative on the interval <math>[1, \infty)</math>, and is also decreasing on that interval since we have made the assumption that <math>p > 0</math>. Moreover, it is obvious that <math>f(i) = \frac{1}{i^p}</math> for every positive integer <math>i</math>. If <math>p \neq 1</math>, then | |The function <math>f</math> defined by <math>f(x) = \frac{1}{x^p}</math> is nonnegative on the interval <math>[1, \infty)</math>, and is also decreasing on that interval since we have made the assumption that <math>p > 0</math>. Moreover, it is obvious that <math>f(i) = \frac{1}{i^p}</math> for every positive integer <math>i</math>. If <math>p \neq 1</math>, then | ||

| Line 153: | Line 154: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

'''Example''' | |||

Determine whether the series <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{2k^2 + 1}</math> converges or diverges. The function <math>f</math> defined by <math>f(x) = \frac{1}{2x^2 + 1}</math> is nonnegative and decreasing on the interval <math>[1, \infty)</math>, and obviously <math>f(k) = \frac{1}{2k^2 + 1}</math>. Since | Determine whether the series <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{2k^2 + 1}</math> converges or diverges. The function <math>f</math> defined by <math>f(x) = \frac{1}{2x^2 + 1}</math> is nonnegative and decreasing on the interval <math>[1, \infty)</math>, and obviously <math>f(k) = \frac{1}{2k^2 + 1}</math>. Since | ||

| Line 203: | Line 204: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

and the proof is complete.}} | and the proof is complete.}} | ||

<span id="eq9.3.3"/> | <span id="eq9.3.3"/> | ||

'''Example''' | '''Example''' | ||

Use the Comparison Test to prove that the series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty \frac{1}{2i^2 - 7}</math> converges. We first observe that the first two terms of the series are negative. However, <math>2i^2 - 7 > 0</math> provided <math>i \geq 2</math>, and so the series <math>\sum_{i=2}^\infty \frac{1}{2i^2 - 7}</math> is nonnegative. It is sufficient to prove the latter series convergent because of the important fact that the convergence of an infinite series is unaffected by any finite number of terms at the beginning. As our test series we take the convergent <math>p</math>-series <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{i^2}</math>. To use the Comparison Test, we wish to show that | Use the Comparison Test to prove that the series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty \frac{1}{2i^2 - 7}</math> converges. We first observe that the first two terms of the series are negative. However, <math>2i^2 - 7 > 0</math> provided <math>i \geq 2</math>, and so the series <math>\sum_{i=2}^\infty \frac{1}{2i^2 - 7}</math> is nonnegative. It is sufficient to prove the latter series convergent because of the important fact that the convergence of an infinite series is unaffected by any finite number of terms at the beginning. As our test series we take the convergent <math>p</math>-series <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{i^2}</math>. To use the Comparison Test, we wish to show that | ||

| Line 225: | Line 228: | ||

which is slightly weaker than (3). However, (4) is certainly sufficient. We know that the series <math>\sum_{i=3}^\infty \frac{1}{i^2}</math> , converges. It follows from (4) by the Comparison Test that <math>\sum_{i=3}^\infty \frac{1}{2i^2 - 7}</math> converges and, as a result, the original series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty \frac{1}{2i^2 - 7}</math> does also. | which is slightly weaker than (3). However, (4) is certainly sufficient. We know that the series <math>\sum_{i=3}^\infty \frac{1}{i^2}</math> , converges. It follows from (4) by the Comparison Test that <math>\sum_{i=3}^\infty \frac{1}{2i^2 - 7}</math> converges and, as a result, the original series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty \frac{1}{2i^2 - 7}</math> does also. | ||

Example 2 illustrates a useful extension of the Comparison Test: ''The series | Example 2 illustrates a useful extension of the Comparison Test: ''The series <math>\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i</math> converges if there exists a convergent series <math>\sum_{i=m}^\infty b_i</math> such that <math>0 \leq a_i \leq b_i</math> eventually.'' The assertion that <math>0 \leq a_i \leq b_i</math> '''eventually''' means simply that there exists an integer <math>N</math> such that <math>0 \leq a_i \leq b_i</math> for every integer <math>i \geq N</math>. The just)fication for this extension is Theorem (2.3), page 486. A similar observation should be made about the Integral Test. It may be necessary to drop a finite number of terms from the beginning of the series under consideration before a convenient function <math>f</math> can be found which satisfies the conditions of the test. | ||

The Comparison Test is as useful for proving divergence as convergence. It is an immediate corollary that ''if the nonnegative series | |||

The Comparison Test is as useful for proving divergence as convergence. It is an immediate corollary that ''if the nonnegative series <math>\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i</math> diverges and if <math>a_i \leq b_i</math> for every <math>i \geq m</math>, then <math>\sum_{i=m}^\infty b_i</math> also diverges.'' For if <math>\sum_{i=m}^\infty b_i</math> converges, the Comparison Test implies that <math>\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i</math> converges, which is contrary to assumption. | |||

<span id="eq9.3.5"/> | <span id="eq9.3.5"/> | ||

'''Example''' | '''Example''' | ||

Determine whether the series <math>\sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{(k^2 + 5)^{1/3}}</math> converges or diverges. If we use the Comparison Test, we must decide whether to look for a convergent test series with larger terms to prove convergence, or a divergent test series with smaller terms to prove divergence. To decide which, observe that for large values of <math>k</math>, the number <math>k^2 + 5</math> is not very different from <math>k^2</math>, and therefore <math>\frac{1}{(k^2 + 5)^{1/3}}</math> is approximately equal to <math>\frac{1}{k^{2/3}}</math>. Stated more formally, we have | Determine whether the series <math>\sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{(k^2 + 5)^{1/3}}</math> converges or diverges. If we use the Comparison Test, we must decide whether to look for a convergent test series with larger terms to prove convergence, or a divergent test series with smaller terms to prove divergence. To decide which, observe that for large values of <math>k</math>, the number <math>k^2 + 5</math> is not very different from <math>k^2</math>, and therefore <math>\frac{1}{(k^2 + 5)^{1/3}}</math> is approximately equal to <math>\frac{1}{k^{2/3}}</math>. Stated more formally, we have | ||

| Line 257: | Line 263: | ||

This inequality is equivalent to <math>8k^2 \geq k^2 + 5</math>, and hence to <math>7k^2 \geq 5</math>, which is certainly true for every positive integer <math>k</math>. Hence (5) holds for every integer <math>k \geq 1</math>, and it therefore follows by the Comparison Test that the series <math>\sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{(k^2 + 5)^{1/3}}</math> diverges. | This inequality is equivalent to <math>8k^2 \geq k^2 + 5</math>, and hence to <math>7k^2 \geq 5</math>, which is certainly true for every positive integer <math>k</math>. Hence (5) holds for every integer <math>k \geq 1</math>, and it therefore follows by the Comparison Test that the series <math>\sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{(k^2 + 5)^{1/3}}</math> diverges. | ||

==General references== | ==General references== | ||

{{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | {{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | ||

Latest revision as of 02:17, 20 November 2024

The theory of convergence of infinite series is in many respects simpler for those series which do not contain both positive and negative terms. A series which contains no negative terms is called nonnegative. Thus [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i[/math] is nonnegative if and only if [math]a_i \geq 0[/math] for every integer [math]i \geq m[/math]. In this section we shall study two convergence criteria for such series: The Integral Test and the Comparison Test. Let [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i[/math] be an arbitrary infinite series (not necessarily nonnegative), and let [math]\{ s_n \}[/math] be the corresponding sequence of partial sums. We recall that [math]s_n = \sum_{i=m}^n a_i[/math], for every integer [math]n \geq m[/math], and that, if [math]\{ s_n \}[/math] converges, then [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_n[/math]. We shall extend the convention regarding the symbol [math]\infty[/math] and write

if and only if [math]\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_n = \infty \; (\mbox{or}\; - \infty)[/math]. It may very well happen that a series neither converges nor satisfies [math]\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} a_i = \pm \infty[/math]. For example, the divergent series

has for its sequence of partial sums the oscillating sequence 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, .... However, for nonnegative series, there are only two alternatives:

Every nonnegative series [math]\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} a_i[/math] either convefges or satisfies [math]\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} a_i = \infty[/math] .

The proof of this fact follows directly from the following two lemmas:

If [math]\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} a_i[/math] is a nonnegative series, then the corresponding sequence [math]\{s\}[/math] of partial sums is an increasing sequence.

For every integer [math]n \geq m[/math], we have [math]s_{n+1} = s_n + a_{n+1}[/math]. Since the series is nonnegative, it follows that [math]s_{n+1} - s_n = a_{n+1} \geq 0[/math]. Hence

If [math]\{ s_n \}[/math] is an increasing infinite sequence of real numbers, then either it is bounded above and therefore converges or else [math]\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_n = \infty[/math].

If the sequence is bounded above, then it is proved in Theorem ( 1.4), page 479, that it must converge. Suppose it is not so bounded. Then, for every real number [math]B[/math], there exists an integer [math]N[/math] such that [math]s_N \gt B[/math]. Since the sequence is increasing, it follows that [math]s_n \geq s_N[/math] for every [math]n \gt N[/math]. Hence [math]s_n \gt B[/math], for every integer [math]n \gt N[/math], and this is precisely the definition of the expression [math]\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_n = \infty[/math].

We come now to the first of the tests for convergence of nonnegative infinite series. It is a generalization of the method used in Section 2 to prove the divergence of the harmonic series.

INTEGRAL TEST. Let [math]f[/math] be a function which is nonnegative and decreasing on the interval [math][m, \infty)[/math]. Then the infinite series [math]\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} a_i[/math] defined by

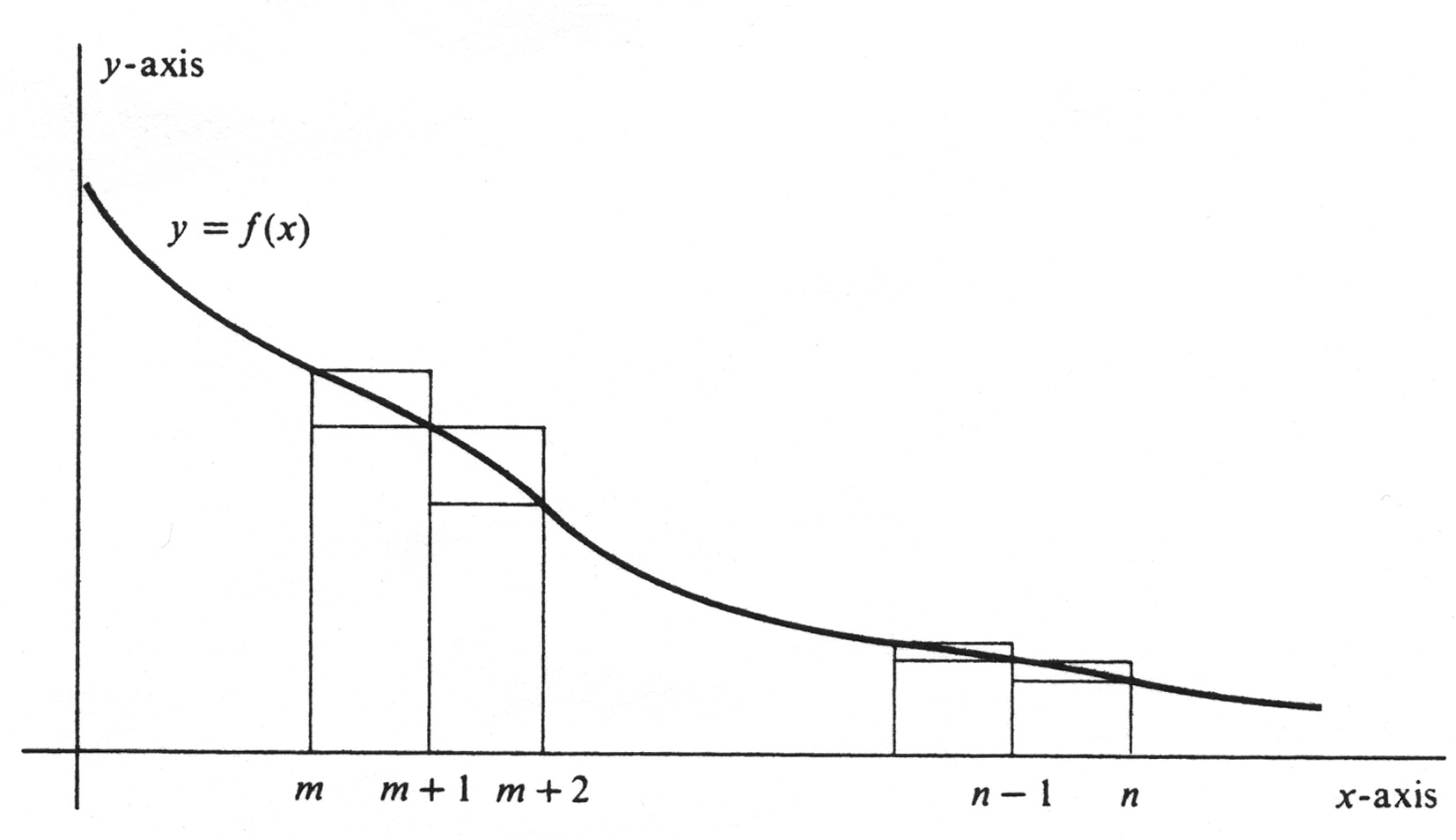

The series [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i[/math] is nonnegative, and its corresponding sequence [math]\{ s_n \}[/math] of partial sums is therefore increasing. Figure 4 illustrates the graph of the function [math]f[/math] over an interval [math][m, n][/math], where [math]n[/math] is an arbitrary integer greater than [math]m[/math]. Since [math]f[/math] is decreasing, its maximum value on each subinterval of the partition [math]\sigma = \{ m, m + 1, . . ., n \}[/math], occurs at the left endpoint. Moreover, each subinterval has length 1. Hence the upper sum [math]U_\sigma[/math], which is equal to the sum of the areas of the rectangles Iying above the graph in the figure, is given by

The convergence or divergence of many infinite series can be determined easily by the Integral Test. Important among these are series of the form

where [math]p[/math] is a positive real number. Such a series is called a [math]p[/math]-series. An example is the divergent harmonic series, for which [math]p = 1[/math]. The basic convergence theorem is

The [math]p[/math]-series [math]\sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{i^p}[/math] converges if and only if [math]p \gt 1[/math].

The function [math]f[/math] defined by [math]f(x) = \frac{1}{x^p}[/math] is nonnegative on the interval [math][1, \infty)[/math], and is also decreasing on that interval since we have made the assumption that [math]p \gt 0[/math]. Moreover, it is obvious that [math]f(i) = \frac{1}{i^p}[/math] for every positive integer [math]i[/math]. If [math]p \neq 1[/math], then

Thus the first of the following three p-series diverges, and the last two converge:

Example

Determine whether the series [math]\sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{2k^2 + 1}[/math] converges or diverges. The function [math]f[/math] defined by [math]f(x) = \frac{1}{2x^2 + 1}[/math] is nonnegative and decreasing on the interval [math][1, \infty)[/math], and obviously [math]f(k) = \frac{1}{2k^2 + 1}[/math]. Since

we have

Hence the integral is convergent, and therefore so is the series.

We come now to the second of our convergence tests.

COMPARISON TEST. [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i[/math] is a nonnegative series and if [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty b_i[/math] is a convergent series with [math]a_i \leq b_i[/math] for every [math]i \geq m[/math], then [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i[/math] converges and [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i \leq \sum_{i=m}^\infty b_i[/math] .

Let [math]\{s_n\}[/math] and [math]\{t_n\}[/math] be the sequences of partial sums for [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i[/math] and [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty b_i[/math], respectively. The hypotheses [math]0 \leq a_i \leq b_i[/math] imply that

Example

Use the Comparison Test to prove that the series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty \frac{1}{2i^2 - 7}[/math] converges. We first observe that the first two terms of the series are negative. However, [math]2i^2 - 7 \gt 0[/math] provided [math]i \geq 2[/math], and so the series [math]\sum_{i=2}^\infty \frac{1}{2i^2 - 7}[/math] is nonnegative. It is sufficient to prove the latter series convergent because of the important fact that the convergence of an infinite series is unaffected by any finite number of terms at the beginning. As our test series we take the convergent [math]p[/math]-series [math]\sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{i^2}[/math]. To use the Comparison Test, we wish to show that

This inequality is equivalent to [math]i^2 \leq 2i^2 - 7[/math], which in turn is equivalent to [math]i^2 \geq 7[/math]. The last is clearly true provided [math]i \geq 3[/math]. Thus we have proved

which is slightly weaker than (3). However, (4) is certainly sufficient. We know that the series [math]\sum_{i=3}^\infty \frac{1}{i^2}[/math] , converges. It follows from (4) by the Comparison Test that [math]\sum_{i=3}^\infty \frac{1}{2i^2 - 7}[/math] converges and, as a result, the original series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty \frac{1}{2i^2 - 7}[/math] does also.

Example 2 illustrates a useful extension of the Comparison Test: The series [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i[/math] converges if there exists a convergent series [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty b_i[/math] such that [math]0 \leq a_i \leq b_i[/math] eventually. The assertion that [math]0 \leq a_i \leq b_i[/math] eventually means simply that there exists an integer [math]N[/math] such that [math]0 \leq a_i \leq b_i[/math] for every integer [math]i \geq N[/math]. The just)fication for this extension is Theorem (2.3), page 486. A similar observation should be made about the Integral Test. It may be necessary to drop a finite number of terms from the beginning of the series under consideration before a convenient function [math]f[/math] can be found which satisfies the conditions of the test.

The Comparison Test is as useful for proving divergence as convergence. It is an immediate corollary that if the nonnegative series [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i[/math] diverges and if [math]a_i \leq b_i[/math] for every [math]i \geq m[/math], then [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty b_i[/math] also diverges. For if [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty b_i[/math] converges, the Comparison Test implies that [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i[/math] converges, which is contrary to assumption.

Example

Determine whether the series [math]\sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{(k^2 + 5)^{1/3}}[/math] converges or diverges. If we use the Comparison Test, we must decide whether to look for a convergent test series with larger terms to prove convergence, or a divergent test series with smaller terms to prove divergence. To decide which, observe that for large values of [math]k[/math], the number [math]k^2 + 5[/math] is not very different from [math]k^2[/math], and therefore [math]\frac{1}{(k^2 + 5)^{1/3}}[/math] is approximately equal to [math]\frac{1}{k^{2/3}}[/math]. Stated more formally, we have

This comparison, together with the divergence of the [math]p[/math]-series [math]\sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{k^{2/3}}[/math], leads us to believe that the series [math]\sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{(k^2 + 5)^{1/3}}[/math] diverges. Hence we shall try a

divergent test series. The most obvious candidate, [math]\sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{k^{2/3}}[/math], fails to be useful, since the necessary inequality,

is clearly false for every value of [math]k[/math]. However, the series [math]\sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{2k^{2/3}}[/math] is also divergent, and we may ask whether or not it is true that

This inequality is equivalent to [math]8k^2 \geq k^2 + 5[/math], and hence to [math]7k^2 \geq 5[/math], which is certainly true for every positive integer [math]k[/math]. Hence (5) holds for every integer [math]k \geq 1[/math], and it therefore follows by the Comparison Test that the series [math]\sum_{k=1}^\infty \frac{1}{(k^2 + 5)^{1/3}}[/math] diverges.

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.