guide:Aa2c92d8a2: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

\newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb} | \newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb} | ||

</math></div> | </math></div> | ||

Associated with every infinite sequence of real numbers <math>a_0, a_1, a_2, . . .</math> and every real number <math>x</math>, there is the infinite series | Associated with every infinite sequence of real numbers <math>a_0, a_1, a_2, . . .</math> and every real number <math>x</math>, there is the infinite series | ||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i} x^i = a_0 + a_{1} x + a_{2} x^2 + \cdots . | \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i} x^i = a_0 + a_{1} x + a_{2} x^2 + \cdots . | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

Such a series is called a '''power series in | Such a series is called a '''power series in <math>x</math>'''. As a general rule, it will converge for some values of <math>x</math>, but not all. For example, the geometric series | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

That is, we have shown that <math>|a_{n}x^n| \leq r^n</math> eventually. Since the geometric series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty r^i</math> converges if <math>|r| < 1</math>, it follows by the Comparison Test that <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty |a_{i} x^i|</math> converges. This completes the proof.}} | That is, we have shown that <math>|a_{n}x^n| \leq r^n</math> eventually. Since the geometric series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty r^i</math> converges if <math>|r| < 1</math>, it follows by the Comparison Test that <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty |a_{i} x^i|</math> converges. This completes the proof.}} | ||

We shall derive three corollaries of (6.1). The first asserts that the set of all real | We shall derive three corollaries of (6.1). The first asserts that the set of all real numbers <math>x</math> at which a power series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}x^i</math> converges is a nonempty interval on the real line. The set is nonempty because, as is remarked above, it contains the number 0. A set of real numbers is an interval if, whenever it contains two numbers, it contains every number in between those two. Thus we must prove that if the series converges at <math>a</math> and at <math>c</math> and if <math>a < b < c</math>, then it also converges at <math>b</math>. This is quickly done. Suppose first that <math>b \geq 0</math>. Then | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

The second corollary states that ''a power series converges absolutely at every interior point of its interval of convergence.'' The proof is virtually the same as that of the first corollary. Let <math>b</math> be an arbitrary interior point of the interval of convergence. Because it is an interior point, we know there exist | The second corollary states that ''a power series converges absolutely at every interior point of its interval of convergence.'' The proof is virtually the same as that of the first corollary. Let <math>b</math> be an arbitrary interior point of the interval of convergence. Because it is an interior point, we know there exist | ||

real numbers <math>a</math> and <math>c</math> which also lie in the interval and for which <math>a < b < c</math>. As before, if <math>b \geq 0</math>, then <math>|b| < |c|</math>, but if <math>b < 0</math>, then <math>|b| < |a|</math>. In either case it follows from (6.1) that the series converges absolutely at <math>b</math>, and this completes the argument. | real numbers <math>a</math> and <math>c</math> which also lie in the interval and for which <math>a < b < c</math>. As before, if <math>b \geq 0</math>, then <math>|b| < |c|</math>, but if <math>b < 0</math>, then <math>|b| < |a|</math>. In either case it follows from (6.1) that the series converges absolutely at <math>b</math>, and this completes the argument. | ||

The third corollary is the following: ''The interior of the interval | The third corollary is the following: ''The interior of the interval <math>I</math> of convergence of a power series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}x^i</math> is symmetric about the origin.'' That is, if <math>b</math> is an interior point of <math>I</math>, then so is <math>-b</math>. Again, there exist numbers <math>a</math> and <math>c</math> in <math>I</math> such that <math>a < b < c</math>. Now consider the open interval <math>(-c, -a)</math>. It certainly contains <math>-b</math>, and, if we can show that <math>(-c, -a)</math> is a subset of <math>I</math>, then we shall have proved that <math>-b</math> is an interior point of <math>I</math>. Let <math>x</math> be an arbitrary number in <math>(-c, -a)</math>, that is, <math>-c < x < -a</math>. There are the, by now familiar, two possibilities: If <math>x \geq 0</math>, then <math>-a > 0</math> and | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

| Line 105: | Line 105: | ||

Find the interval and radius of convergence of each of the following power series: | Find the interval and radius of convergence of each of the following power series: | ||

<ul style="list-style-type:lower-alpha"> | |||

<li> | |||

<math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty \frac{x^i}{i!} = 1 + x + \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^3}{3!} + \cdots.</math> | |||

</li> | |||

<li> | |||

<math>\sum_{k=1}^\infty(-1)^{k-1} \frac{x^k}{k} = x - \frac{x^2}{2} + \frac{x^3}{3} - \cdots.</math> | |||

</li> | |||

<li> | |||

<math>\sum_{n=0}^\infty n!x^n = 1 + x + 2x^2 + 3!x^3 + \cdots.</math> | |||

</li> | |||

</ul> | |||

In many examples the radius of convergence can be found easily using the Ratio Test. | In many examples the radius of convergence can be found easily using the Ratio Test. | ||

| Line 209: | Line 215: | ||

A power series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x - a)^i</math> is frequently called a power series about the number <math>a</math>. If we recall that <math>|x - a|</math> is geometrically equal to the distance between <math>x</math> and <math>a</math>, we see that the appropriate analogue of theorem (6.2) is: | A power series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x - a)^i</math> is frequently called a power series about the number <math>a</math>. If we recall that <math>|x - a|</math> is geometrically equal to the distance between <math>x</math> and <math>a</math>, we see that the appropriate analogue of theorem (6.2) is: | ||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-3|THEOREM. If the power series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i} (x - a)^i</math> has radius of convergence <math>\rho</math>, then the series converges absolutely at every <math>x</math> such that <math>|x - a| < \rho</math>. If <math>\rho</math> is not infinite, the series diverges at every <math>x</math> such that <math>|x - a| > \rho</math>.|}} | {{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-3|THEOREM. If the power series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i} (x - a)^i</math> has radius of convergence <math>\rho</math>, then the series converges absolutely at every <math>x</math> such that <math>|x - a| < \rho</math>. If <math>\rho</math> is not infinite, the series diverges at every <math>x</math> such that <math>|x - a| > \rho</math>.|}} | ||

'''Example''' | '''Example''' | ||

Find the radius and interval of convergence of the power series | Find the radius and interval of convergence of the power series | ||

| Line 256: | Line 264: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

==General references== | ==General references== | ||

{{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | {{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | ||

Latest revision as of 22:51, 20 November 2024

Associated with every infinite sequence of real numbers [math]a_0, a_1, a_2, . . .[/math] and every real number [math]x[/math], there is the infinite series

Such a series is called a power series in [math]x[/math]. As a general rule, it will converge for some values of [math]x[/math], but not all. For example, the geometric series

converges and has the same value as [math]\frac{1}{1-x}[/math] for every real number [math]x[/math] in absolute value less than 1, but it diverges for all other values of [math]x[/math]. A power series which converges for some real number [math]c[/math], i.e., which converges if [math]x = c[/math], is commonly said to converge at [math]c[/math]. Note that every power series in [math]x[/math] converges at 0, since, if [math]x = 0[/math], then

The following proposition is the basic theorem in studying the convergence of power series:

If a power series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}x^i[/math] converges for some real number [math]c[/math], then it is absolutely conuergent for every real number [math]x[/math] such that [math]|x| \lt |c|[/math].

If [math]c = 0[/math], the result is vacuously true, so we shall assume that [math]c \neq 0[/math]. The fact that the series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}c^i[/math] converges implies that [math]\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} a_{n}c^n= 0[/math]. Hence there exists a nonnegative integer [math]N[/math] such that [math]|a_{n}c^n| \leq 1[/math], for every integer [math]n \geq N[/math]. Since [math]|a_{n}c^n| = |a_n| |c^n|[/math], it follows that

We shall derive three corollaries of (6.1). The first asserts that the set of all real numbers [math]x[/math] at which a power series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}x^i[/math] converges is a nonempty interval on the real line. The set is nonempty because, as is remarked above, it contains the number 0. A set of real numbers is an interval if, whenever it contains two numbers, it contains every number in between those two. Thus we must prove that if the series converges at [math]a[/math] and at [math]c[/math] and if [math]a \lt b \lt c[/math], then it also converges at [math]b[/math]. This is quickly done. Suppose first that [math]b \geq 0[/math]. Then

and (6.1) implies that the series converges at [math]b[/math]. On the other hand, if [math]b \lt 0[/math], then

and it again follows from (6.1) that the'series converges at [math]b[/math]. This completes the proof, and, as a result, we call the set of all numbers at which a power series converges the interval of convergence of the power series. A number [math]a[/math] is called an interior point of a set [math]S[/math] of real numbers if there exists an open interval which contains [math]a[/math] and which is a subset of [math]S[/math]. The set of all interior points of [math]S[/math] is called the interior of [math]S[/math]. For example, if [math]S[/math] is itself an open interval, then all its points are interior points and hence [math]S[/math] equals its own interior. More generally, the interior of an arbitrary interval consists of the interval with its endpoints deleted. The second corollary states that a power series converges absolutely at every interior point of its interval of convergence. The proof is virtually the same as that of the first corollary. Let [math]b[/math] be an arbitrary interior point of the interval of convergence. Because it is an interior point, we know there exist real numbers [math]a[/math] and [math]c[/math] which also lie in the interval and for which [math]a \lt b \lt c[/math]. As before, if [math]b \geq 0[/math], then [math]|b| \lt |c|[/math], but if [math]b \lt 0[/math], then [math]|b| \lt |a|[/math]. In either case it follows from (6.1) that the series converges absolutely at [math]b[/math], and this completes the argument. The third corollary is the following: The interior of the interval [math]I[/math] of convergence of a power series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}x^i[/math] is symmetric about the origin. That is, if [math]b[/math] is an interior point of [math]I[/math], then so is [math]-b[/math]. Again, there exist numbers [math]a[/math] and [math]c[/math] in [math]I[/math] such that [math]a \lt b \lt c[/math]. Now consider the open interval [math](-c, -a)[/math]. It certainly contains [math]-b[/math], and, if we can show that [math](-c, -a)[/math] is a subset of [math]I[/math], then we shall have proved that [math]-b[/math] is an interior point of [math]I[/math]. Let [math]x[/math] be an arbitrary number in [math](-c, -a)[/math], that is, [math]-c \lt x \lt -a[/math]. There are the, by now familiar, two possibilities: If [math]x \geq 0[/math], then [math]-a \gt 0[/math] and

If [math]x \lt 0[/math], then [math]-c \lt 0[/math], whence [math]c \gt 0[/math], and

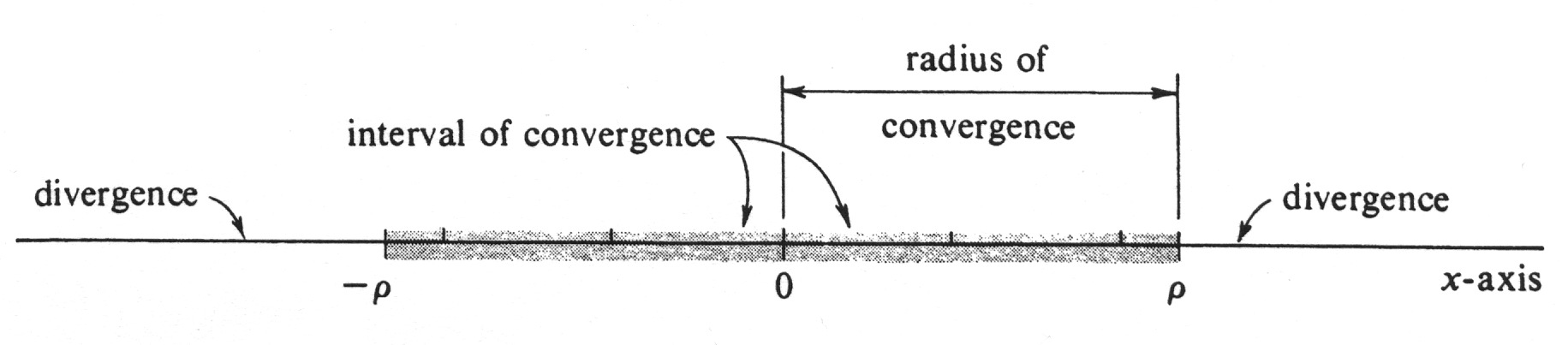

For either possibility, the convergence of the series at [math]x[/math] is implied by (6.1), and so the third corollary is proved. If a power series converges for every real number, then its interval of convergence is the set of all real numbers. The only other possibility, according to the third corollary above, is that the interval of convergence is bounded with symmetrically located endpoints [math]-\rho[/math] and [math]\rho[/math]. We define the radius of convergence of a power series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}x^i[/math] to be infinite if the interval of convergence is the set [math](-\infty, \infty)[/math] of all real numbers, and to be the right endpoint of the interval of convergence if the interval is bounded. The preceding results are then summarized in Figure 6 below and in the following theorem:

lf a power series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}x^i[/math] has radius of convergence [math]\rho[/math], then the series converges absolutely at every [math]x[/math] in the open interval [math](-\rho, \rho)[/math]. lf [math]\rho[/math] is not infinite, then [math]-\rho[/math] and [math]\rho[/math] are the endpoints of the interval of convergence.

It is important to realize that, when [math]\rho[/math] is finite, we have made no prediction as to whether the series converges or diverges at [math]\rho[/math] and at [math]-\rho[/math]. All we know is that it converges absolutely in the open interval [math](-\rho, \rho)[/math] and diverges outside the closed interval [math][-\rho, \rho][/math].

Example

Find the interval and radius of convergence of each of the following power series:

- [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty \frac{x^i}{i!} = 1 + x + \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^3}{3!} + \cdots.[/math]

- [math]\sum_{k=1}^\infty(-1)^{k-1} \frac{x^k}{k} = x - \frac{x^2}{2} + \frac{x^3}{3} - \cdots.[/math]

- [math]\sum_{n=0}^\infty n!x^n = 1 + x + 2x^2 + 3!x^3 + \cdots.[/math]

In many examples the radius of convergence can be found easily using the Ratio Test. For the series in (a), we set [math]u_i = \frac{x^i}{i!}[/math] and form the ratio

Since [math](n+ 1)! = (n + 1)n![/math],

Hence

It follows from the Ratio Test that the series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty \frac{x^i}{i!}[/math] is absolutely convergent for every real number [math]x[/math]. Hence the interval of convergence is the entire real line, and the radius of convergence is infinite. Let [math]u_k = (-1)^{k-1} \frac{x^k}{k}[/math] for the series in (b). For every integer [math]k \geq 1[/math], we have [math]|u_k| = \frac{|x|^k}{k}[/math]. Hence

Since

we obtain

The Ratio Test therefore implies that the series [math]\sum_{k=0}^\infty (-1)^{k-1} \frac{x^k}{k}[/math] converges absolutely if [math]|x| \lt 1[/math] and diverges if [math]|x| \gt 1[/math]. It follows that the endpoints of the interval of convergence are the numbers [math]-1[/math] and 1 and that the radius of convergence is 1. If [math]x = 1[/math], the series becomes

which is the convergent alternating harmonic series. On the other hand, if [math]x = -1[/math], the series becomes

Since [math]2k - 1[/math] is always an odd integer, we have [math](-1)^{2k-1} = -1[/math], and so

which diverges. Hence the interval of convergence of the power series [math]\sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1)^{k-1} \frac{x^k}{k}[/math] is the half-open interval [math](-1, 1][/math]. For the series in (c), let [math]u_n = n! x^n[/math]. We then get

It follows that

From the Ratio Test we conclude that the series [math]\sum_{n=0}^\infty n! x^n[/math] converges only at [math]x = 0[/math]. The radius of convergence is therefore equal to 0, and the interval of convergence contains the one number 0.

A significant generalization of the definition of power series can be made as follows: Consider an arbitrary real number a and an infinite sequence of real numbers [math]a_0, a_1, a_2, ...[/math]. For every real number [math]x[/math], a power series in [math]x-a[/math] is defined by

The power series in [math]x[/math] studied earlier in this section are simply instances of the present definition for which [math]a = 0[/math]. Fortunately, it is not necessary to start from the beginning again to develop the theory of convergence of power series in [math]x - a[/math]. Consider the power series in [math]y[/math] obtained by making the substitution [math]x - a = y[/math] in the series (1). We obtain

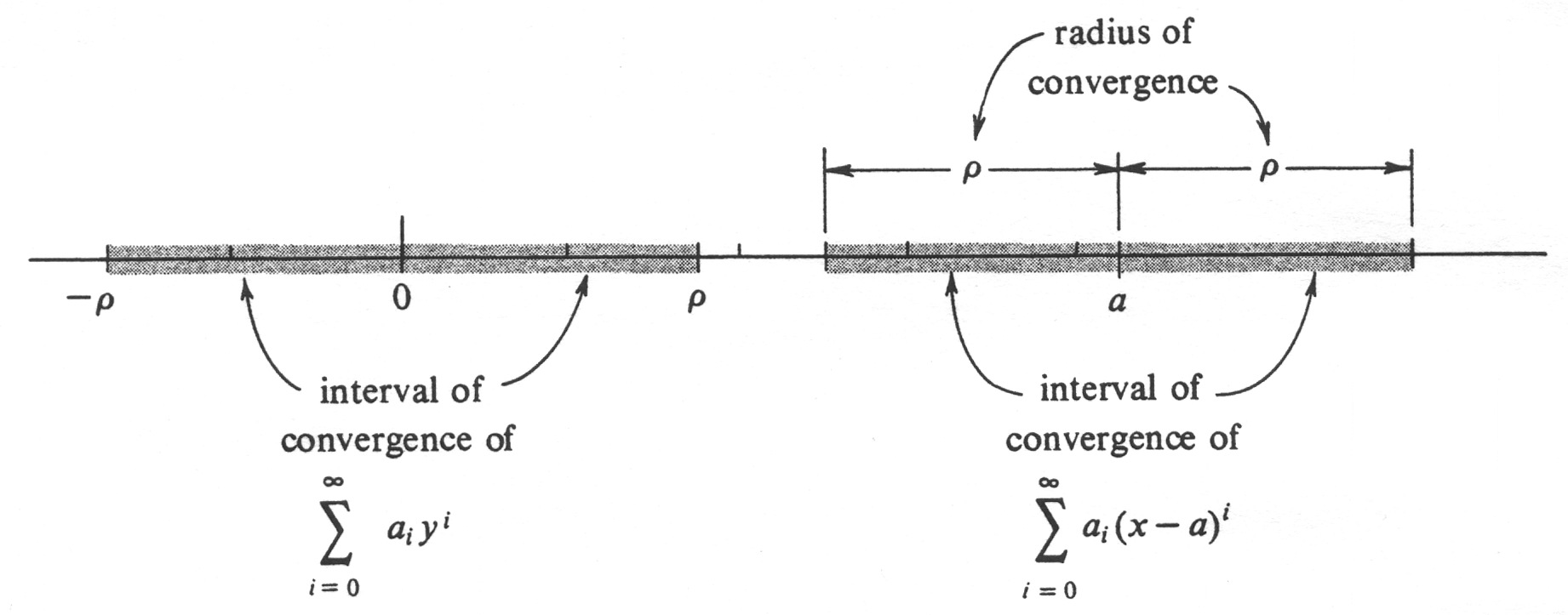

Let [math]I[/math] be the set of all real numbers [math]y[/math] for which (2) converges, i.e., the interval of convergence of the power series (2). Similarly, let [math]J[/math] be the set of all real numbers [math]x[/math] for which (1) converges. Since [math]x - a = y[/math], or equivalently, [math]x = y + a[/math], a number [math]b[/math] will belong to [math]I[/math] if and only if [math]b + a[/math] belongs to [math]J[/math]. Thus the set [math]J[/math] consists of all numbers of the form [math]b + a[/math], where [math]b[/math] belongs to [math]I[/math]. Symbolically, we write

Geometrically, therefore, the set [math]J[/math] is obtained by translating the interval [math]I[/math] along the real line a distance [math]|a|[/math], translating to the right if [math]a \gt 0[/math], and to the left if [math]a \lt 0[/math] (see Figure 7). Hence, the set [math]J[/math] of all real numbers [math]x[/math] for which [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i} (x - a)^i[/math] converges is also an interval, and is called the interval of convergence of that series. The corresponding radius of convergence is equal to the radius of convergence of the series (2), but this time it should be interpreted (if it is not infinite) as the distance from the number [math]a[/math] to the right endpoint of the interval of convergence [math]J[/math]. The interior of [math]J[/math] is, of course, symmetric about the number [math]a[/math]. A power series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x - a)^i[/math] is frequently called a power series about the number [math]a[/math]. If we recall that [math]|x - a|[/math] is geometrically equal to the distance between [math]x[/math] and [math]a[/math], we see that the appropriate analogue of theorem (6.2) is:

THEOREM. If the power series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i} (x - a)^i[/math] has radius of convergence [math]\rho[/math], then the series converges absolutely at every [math]x[/math] such that [math]|x - a| \lt \rho[/math]. If [math]\rho[/math] is not infinite, the series diverges at every [math]x[/math] such that [math]|x - a| \gt \rho[/math].

Example

Find the radius and interval of convergence of the power series

Observe, first of all, that this is a power series about the number [math]-2[/math]. That is, to put it in the standard form (1), we must write the series as

Let us set [math]u_n = \frac{1}{3^n} (x + 2)^n[/math] and apply the Ratio Test. For every integer [math]n \geq 0[/math], we obtain

Hence

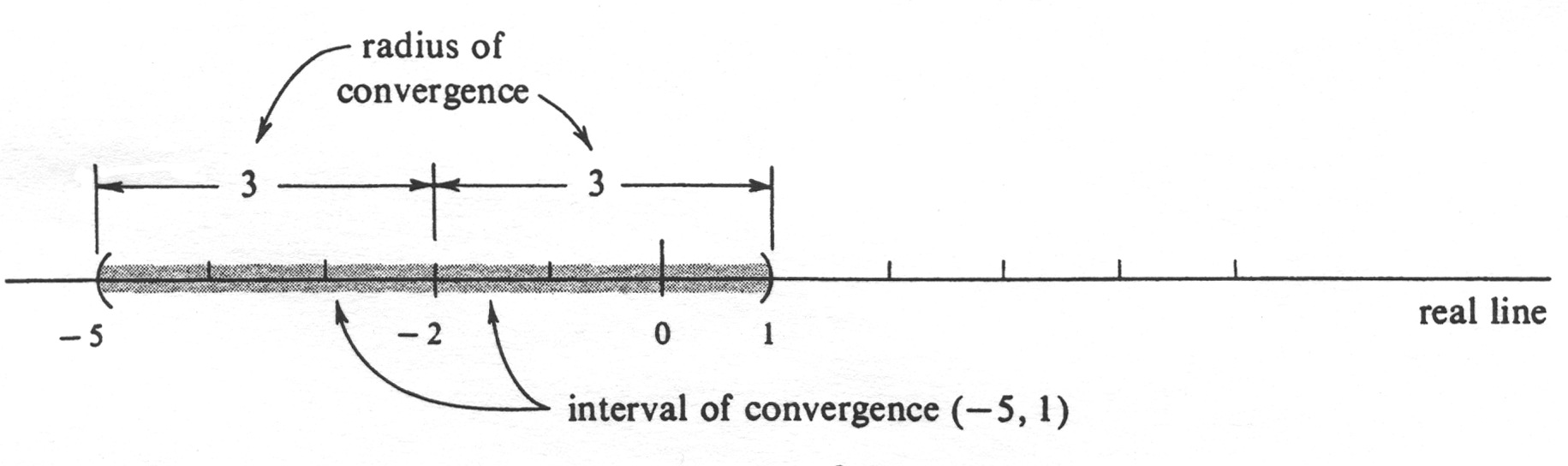

The series is therefore absolutely convergent if [math]q \lt 1[/math], or, equivalently, if [math]|x + 2| \lt 3[/math], and it is divergent if [math]q \gt 1[/math], or, equivalently, if [math]|x + 2| \gt 3[/math]. Remember that [math]|x + 2|[/math] is the distance between [math]x[/math] and [math]-2[/math]. Thus the interior of the interval of convergence is the set of all real numbers whose distance from [math]-2[/math] is less than 3. Hence the radius of convergence is equal to 3, and the endpoints of the interval of convergence are the numbers [math]-5[/math] and 1. If [math]x = - 5[/math], the series becomes

which diverges. If [math]x = 1[/math], we also obtain a divergent series,

It follows that the interval of convergence of the power series

is the open interval [math](-5, 1)[/math] (see Figure 8).

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.