guide:A1750b278c: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="d-none"><math> | |||

\newcommand{\ex}[1]{\item } | |||

\newcommand{\sx}{\item} | |||

\newcommand{\x}{\sx} | |||

\newcommand{\sxlab}[1]{} | |||

\newcommand{\xlab}{\sxlab} | |||

\newcommand{\prov}[1] {\quad #1} | |||

\newcommand{\provx}[1] {\quad \mbox{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\intext}[1]{\quad \mbox{#1} \quad} | |||

\newcommand{\R}{\mathrm{\bf R}} | |||

\newcommand{\Q}{\mathrm{\bf Q}} | |||

\newcommand{\Z}{\mathrm{\bf Z}} | |||

\newcommand{\C}{\mathrm{\bf C}} | |||

\newcommand{\dt}{\textbf} | |||

\newcommand{\goesto}{\rightarrow} | |||

\newcommand{\ddxof}[1]{\frac{d #1}{d x}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddx}{\frac{d}{dx}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddt}{\frac{d}{dt}} | |||

\newcommand{\dydx}{\ddxof y} | |||

\newcommand{\nxder}[3]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{d{#3}^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\deriv}[2]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{dx^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\dist}{\mathrm{distance}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccot}{\mathrm{arccot\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccsc}{\mathrm{arccsc\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsec}{\mathrm{arcsec\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arctanh}{\mathrm{arctanh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsinh}{\mathrm{arcsinh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccosh}{\mathrm{arccosh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\sech}{\mathrm{sech\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\csch}{\mathrm{csch\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\conj}[1]{\overline{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb} | |||

</math></div> | |||

In solving linear differential equations, we have encountered many combinations of <math>e^{r_1x}</math> and <math>e^{r_2x}</math>. Among these, two particular linear combinations occur sufficiently often that they have been given special names. These are the two functions <math>\frac{1}{2} e^x + \frac{1}{2} e^{-x}</math> and <math>\frac{1}{2} e^x - \frac{1}{2=== | |||

e^{-x}</math>. | |||

Let us look at some of the properties of these two functions, which motivate their names. First, we observe that each is the derivative of the other: | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\frac{d}{dx} (\frac{1}{2} e^x + \frac{1}{2} e^{-x}) = \frac{1}{2} e^x - \frac{1}{2} e^{-x} ,\\ | |||

\frac{d}{dx} (\frac{1}{2} e^x - \frac{1}{2} e^{-x}) = \frac{1}{2} e^x + \frac{1}{2} e^{-x} . | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

This fact implies, of course, that each function is its own second derivative. There is a clear analogy here with the trigonometric functions cosine and sine, each of which is, up to sign, the derivative of the other and each of which is the negative of its own second derivative. | |||

The result of squaring these two functions is | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

(\frac{1}{2} e^x + \frac{1}{2} e^x)^2 = \frac{1}{4} e^{2x} + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{4} e^{-2x},\\ | |||

(\frac{1}{2} e^x - \frac{1}{2} e^x)^2 = \frac{1}{4} e^{2x} + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{4} e^{-2x}, | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

from which it follows that | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq11.6.1"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

(\frac{1}{2} e^x + \frac{1}{2} e^{-x})^2 - (\frac{1}{2} e^x - \frac{1}{2} e^{-x})^2 = 1. | |||

\label{eq11.6.1} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

Thus the difference of their squares is equal to 1, and this fact is analogous to the trigonometric identity <math>\cos^2x + \sin^2x = 1</math>. It is a consequence of equation (1) that, for every real number <math>t</math>, the ordered pair | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

(x,y) = (\frac{1}{2} e^t + \frac{1}{2} e^{-t}, \frac{1}{2} e^t - \frac{1}{2} e^{-t}) | |||

</math> | |||

satisfies the equation <math>x^2 - y^2 = 1</math> of an equilateral hyperbola. Similarly, we know that, for every real number <math>t</math>, the ordered pair | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

(x, y) = (\cos t, \sin t) | |||

</math> | |||

is a point on the unit circle <math>x^2 + y^2 = 1</math>. With this motivation, we define the '''hyperbolic cosine,''' abbreviated <math>\cosh</math>, and the '''hyperbolic sine,''' abbreviated <math>\sinh</math>, by setting | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq11.6.2"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

\begin{array}{ll} | |||

\cosh x &= \frac{1}{2}e^x + \frac{1}{2}e^{-x}, \\ | |||

\sinh x &= \frac{1}{2}e^x - \frac{1}{2}e^{x}, \;\;\;\mbox{for every real number}\; x. | |||

\label{eq11.6.2} | |||

\end{array} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

It is trivial to verify that | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-1| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\cosh(-x) &=& \cosh x, \\ | |||

\sinh(-x) &=& -\sinh x,\;\;\;\mbox{for every real number}\; x. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math>|}} | |||

Thus, like their respective trigonometric counterparts, the hyperbolic cosine is an even function, and the hyperbolic sine is an odd function. | |||

Equation (1) now becomes the identity | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-2| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\cosh^2 x - \sinh^2 x = 1, \;\;\;\mbox{for every real number}\; x, | |||

</math>|}} | |||

and we have also already established the two derivative formulas | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-3| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\frac{d}{dx} \cosh x = \sinh x, | |||

</math>|}} | |||

and | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-4| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\frac{d}{dx} \sinh x = \cosh x. | |||

</math>|}} | |||

Sinee each of the two functions, <math>\cosh</math> and <math>\sinh</math>, is equal to its own second derivative, eaeh is a solution of the differential equation <math>(D^2 - 1)y = 0</math>. More generally, the functions <math>\cosh kx</math> and <math>\sinh kx</math>, where <math>k</math> is an arbitrary real constant, are both solutions of the differential equation | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq11.6.3"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

(D^2 - k^2) y = 0. | |||

\label{eq11.6.3} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

From the linearity of the differential operator <math>D^2 - k^2</math> it follows that the function defined by | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq11.6.4"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

y = c_1 \cosh kx + c_2 \sinh kx, | |||

\label{eq11.6.4} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

for any two real numbers <math>c_1</math> and <math>c_2</math>, is also a solution. In fact, (4) ''is an alternative form of the general solution of the differential equation'' (3). | |||

To prove this faet, let <math>y_0</math> be an arbitrary solution of (3). The characteristic polynomial is <math>t^2 - k^2</math>, which equals the product <math>(t - k)(t + k)</math>. Henee there exist real numbers <math>A</math> and <math>B</math> such that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

y_0 = Ae^{kx} + Be^{-kx} . | |||

</math> | |||

However, we have | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\cosh kx + \sinh kx = \frac{e^{kx}}{2} + \frac{e^{-kx}}{2} + \frac{e^{kx}}{2} - \frac{e^{-kx}}{2} = e^{kx}, \\ | |||

\cosh kx - \sinh kx = \frac{e^{kx}}{2} + \frac{e^{-kx}}{2} - \frac{e^{kx}}{2} + \frac{e^{-kx}}{2} = e^{-kx} | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

It follows that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

y_0 = A(\cosh kx + \sinh kx) + B(\cosh kx - \sinh kx) \\ | |||

= (A + B) \cosh kx + (A - B) \sinh kx, | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

which is of the form of (4). This completes the proof. | |||

In drawing the graphs of the hyperbolic functions, we make use of the fact that cosh is an even function, and sinh is an odd function. In addition, each of the following simple results follows quickly from the definition of the relevant function: | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-5| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\left \{ \begin{array}{rl} | |||

\mathrm{(i)}\; & \cosh 0 = 1, \\ | |||

\mathrm{(ii)}\;& \sinh0 = 0, \\ | |||

\mathrm{(iii)}\;& \cosh x > 0, \;\mbox{for every real number}\; x, \\ | |||

\mathrm{(iv)}\;& \sinh x = 0 \;\mbox{if and only if}\; x = 0, \\ | |||

\mathrm{(v)}\; & \sinh x > 0, \;\mbox{for every}\; x > 0. | |||

\end{array} | |||

\right . | |||

</math>|}} | |||

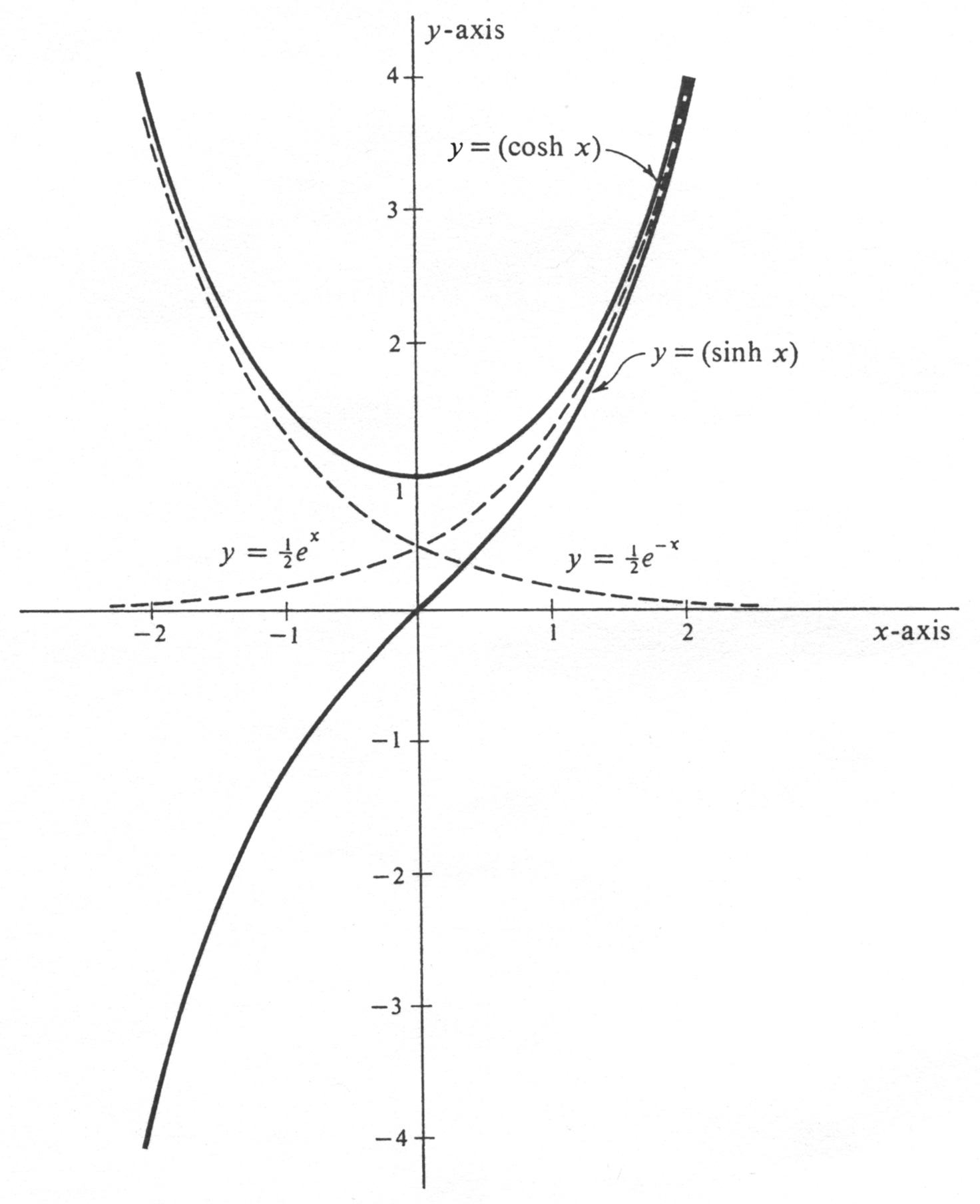

Applying these facts to the first and second derivatives, we conclude that the graph of sinh <math>x</math> has positive slope everywhere, has therefore no local maximum or minimum points, and passes through the origin with slope 1. Moreover, it is concave upward if <math>x</math> is positive, is concave downward if <math>x</math> is negative, and as a result has one point of inflection at the origin. Similarly, the graph of cosh <math>x</math> has positive slope if <math>x</math> is positive, negative slope if <math>x</math> is negative, and one critical point at (0, 1). It is concave upward everywhere, from which it follows that there are no points of inflection and the critical point at (0, 1) is a local minimum. The graphs of the two functions are drawn in the same <math>xy</math>-plane in Figure 2. | |||

The curve which is the graph of the equation <math>y = \cosh x</math> is called a '''catenary.''' More generally, a catenary is the graph of an equation of the form <math>y = a \cosh (\frac{x}{a})</math>, where <math>a</math> is a nonzero constant. The word comes from the a latin word meaning “chain,” and it can be shown that, if a chain or cable with a uniform weight per unit length is suspended between two points, then it hangs in the shape of a catenary. | |||

In a manner completely analogous to that for defining the other four trigonometric functions from the sine and cosine, we define four other hyperbolic functions. They are the '''hyperbolic tangent,''' denoted by tanh; the '''hyperbolic secant,''' denoted by sech; the '''hyperbolic cosecant,''' denoted by csch; and the '''hyperbolic cotangent,''' denoted by cotta. The definitions are | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq11.6.5"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

\begin{array}{ll} | |||

\tanh x = \frac{\sinh x}{\cosh x}, \;\;\; & \mbox{sech}\; x = \frac{1}{\cosh x} \\ | |||

\coth x = \frac{\cosh x}{\sinh x}, \;\;\; & \mbox{csch}\; x = \frac{1}{\sinh x} . | |||

\end{array} | |||

\label{eq11.6.5} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

<div id="fig 11.2" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig11_2.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

In the problems at the end of the section you are asked to find the derivatives of these functions. These derivative formulas, and also the many identities among the hyperbolic functions, are all closely akin to those for the trigonometric functions. | |||

The inverse hyperbolic functions are also defined. For example, <math>y</math> is the inverse hyperbolic cosine of <math>x</math> if and only if <math>x</math> is the hyperbolic cosine of <math>y</math>. That is, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

y = \mbox{arccosh}\; x \;\;\;\mbox{if and only if}\; x = \cosh y. | |||

</math> | |||

The domain of the inverse hyperbolic cosine arccosh is the set of all real numbers greater than or equal to 1, and the range is chosen to be the set of all nonnegative real numbers. The definitions of the other inverse hyperbolic functions follow the same pattern. | |||

==General references== | |||

{{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | |||

Latest revision as of 02:45, 21 November 2024

In solving linear differential equations, we have encountered many combinations of [math]e^{r_1x}[/math] and [math]e^{r_2x}[/math]. Among these, two particular linear combinations occur sufficiently often that they have been given special names. These are the two functions [math]\frac{1}{2} e^x + \frac{1}{2} e^{-x}[/math] and [math]\frac{1}{2} e^x - \frac{1}{2=== e^{-x}[/math]. Let us look at some of the properties of these two functions, which motivate their names. First, we observe that each is the derivative of the other:

This fact implies, of course, that each function is its own second derivative. There is a clear analogy here with the trigonometric functions cosine and sine, each of which is, up to sign, the derivative of the other and each of which is the negative of its own second derivative. The result of squaring these two functions is

from which it follows that

Thus the difference of their squares is equal to 1, and this fact is analogous to the trigonometric identity [math]\cos^2x + \sin^2x = 1[/math]. It is a consequence of equation (1) that, for every real number [math]t[/math], the ordered pair

satisfies the equation [math]x^2 - y^2 = 1[/math] of an equilateral hyperbola. Similarly, we know that, for every real number [math]t[/math], the ordered pair

is a point on the unit circle [math]x^2 + y^2 = 1[/math]. With this motivation, we define the hyperbolic cosine, abbreviated [math]\cosh[/math], and the hyperbolic sine, abbreviated [math]\sinh[/math], by setting

It is trivial to verify that

Thus, like their respective trigonometric counterparts, the hyperbolic cosine is an even function, and the hyperbolic sine is an odd function. Equation (1) now becomes the identity

and we have also already established the two derivative formulas

and

Sinee each of the two functions, [math]\cosh[/math] and [math]\sinh[/math], is equal to its own second derivative, eaeh is a solution of the differential equation [math](D^2 - 1)y = 0[/math]. More generally, the functions [math]\cosh kx[/math] and [math]\sinh kx[/math], where [math]k[/math] is an arbitrary real constant, are both solutions of the differential equation

From the linearity of the differential operator [math]D^2 - k^2[/math] it follows that the function defined by

for any two real numbers [math]c_1[/math] and [math]c_2[/math], is also a solution. In fact, (4) is an alternative form of the general solution of the differential equation (3). To prove this faet, let [math]y_0[/math] be an arbitrary solution of (3). The characteristic polynomial is [math]t^2 - k^2[/math], which equals the product [math](t - k)(t + k)[/math]. Henee there exist real numbers [math]A[/math] and [math]B[/math] such that

However, we have

It follows that

which is of the form of (4). This completes the proof. In drawing the graphs of the hyperbolic functions, we make use of the fact that cosh is an even function, and sinh is an odd function. In addition, each of the following simple results follows quickly from the definition of the relevant function:

Applying these facts to the first and second derivatives, we conclude that the graph of sinh [math]x[/math] has positive slope everywhere, has therefore no local maximum or minimum points, and passes through the origin with slope 1. Moreover, it is concave upward if [math]x[/math] is positive, is concave downward if [math]x[/math] is negative, and as a result has one point of inflection at the origin. Similarly, the graph of cosh [math]x[/math] has positive slope if [math]x[/math] is positive, negative slope if [math]x[/math] is negative, and one critical point at (0, 1). It is concave upward everywhere, from which it follows that there are no points of inflection and the critical point at (0, 1) is a local minimum. The graphs of the two functions are drawn in the same [math]xy[/math]-plane in Figure 2. The curve which is the graph of the equation [math]y = \cosh x[/math] is called a catenary. More generally, a catenary is the graph of an equation of the form [math]y = a \cosh (\frac{x}{a})[/math], where [math]a[/math] is a nonzero constant. The word comes from the a latin word meaning “chain,” and it can be shown that, if a chain or cable with a uniform weight per unit length is suspended between two points, then it hangs in the shape of a catenary. In a manner completely analogous to that for defining the other four trigonometric functions from the sine and cosine, we define four other hyperbolic functions. They are the hyperbolic tangent, denoted by tanh; the hyperbolic secant, denoted by sech; the hyperbolic cosecant, denoted by csch; and the hyperbolic cotangent, denoted by cotta. The definitions are

In the problems at the end of the section you are asked to find the derivatives of these functions. These derivative formulas, and also the many identities among the hyperbolic functions, are all closely akin to those for the trigonometric functions. The inverse hyperbolic functions are also defined. For example, [math]y[/math] is the inverse hyperbolic cosine of [math]x[/math] if and only if [math]x[/math] is the hyperbolic cosine of [math]y[/math]. That is,

The domain of the inverse hyperbolic cosine arccosh is the set of all real numbers greater than or equal to 1, and the range is chosen to be the set of all nonnegative real numbers. The definitions of the other inverse hyperbolic functions follow the same pattern.

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.