guide:239bf7acf2: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="d-none"><math> | |||

\newcommand{\ex}[1]{\item } | |||

\newcommand{\sx}{\item} | |||

\newcommand{\x}{\sx} | |||

\newcommand{\sxlab}[1]{} | |||

\newcommand{\xlab}{\sxlab} | |||

\newcommand{\prov}[1] {\quad #1} | |||

\newcommand{\provx}[1] {\quad \mbox{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\intext}[1]{\quad \mbox{#1} \quad} | |||

\newcommand{\R}{\mathrm{\bf R}} | |||

\newcommand{\Q}{\mathrm{\bf Q}} | |||

\newcommand{\Z}{\mathrm{\bf Z}} | |||

\newcommand{\C}{\mathrm{\bf C}} | |||

\newcommand{\dt}{\textbf} | |||

\newcommand{\goesto}{\rightarrow} | |||

\newcommand{\ddxof}[1]{\frac{d #1}{d x}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddx}{\frac{d}{dx}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddt}{\frac{d}{dt}} | |||

\newcommand{\dydx}{\ddxof y} | |||

\newcommand{\nxder}[3]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{d{#3}^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\deriv}[2]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{dx^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\dist}{\mathrm{distance}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccot}{\mathrm{arccot\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccsc}{\mathrm{arccsc\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsec}{\mathrm{arcsec\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arctanh}{\mathrm{arctanh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsinh}{\mathrm{arcsinh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccosh}{\mathrm{arccosh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\sech}{\mathrm{sech\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\csch}{\mathrm{csch\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\conj}[1]{\overline{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb} | |||

</math></div> | |||

If a function <math>f</math> is integrable over an interval <math>[a, b]</math>, then in the definite integral | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{a}^{b} f = \int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx | |||

</math> | |||

the function <math>f</math> is called the '''integrand''', and the numbers <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> the '''limits of integration'''. | |||

The basic properties of the definite integral are contained in the following five theorems. | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-1|If <math>f (x) = k</math> for every <math>x</math> in the interval <math>[a, b]</math>, then | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx = \int_{a}^{b} k dx = k(b - a). | |||

</math>|}} | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-2|The function <math>f</math> is integrable over the intervals <math>[a, b]</math> and <math>[b, c]</math> if and only if it is integrable over their union <math>[a, c]</math>. Furthermore, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx + \int_{b}^{c} f(x) dx = \int_{a}^{c} f(x) dx. | |||

</math>|}} | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-3|If <math>f</math> and <math>g</math> are integrable over <math>[a, b]</math> and if <math>f (x) \leq g(x)</math> for every <math>x</math> in <math>[a, b]</math>, then | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{a}^{b} f(x)dx \leq \int_{a}^{b} g(x)dx. | |||

</math>|}} | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-4|If <math>f</math> is integrable over <math>[a, b]</math> and if <math>k</math> is any real number, then the product <math>kf</math> is integrable and | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{a}^{b} k f (x) dx = k \int_{a}^{b} f (x) dx. | |||

</math>|}} | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-5|If <math>f</math> and <math>g</math> are integrable over <math>[a, b]</math>, then so is their sum and | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{a}^{b} [f(x) + g(x)] dx = \int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx + \int_{a}^{b} g(x) dx. | |||

</math>|}} | |||

None of the proofs of these theorems is deep in the sense of requiring great ingenuity or any techniques beyond the use of least upper bounds and greatest lower bounds. However, they vary considerably in the amount of detail required. The proof of (4.1) is a triviality. For if <math>f</math> has the constant value <math>k</math> on the interval <math>[a, b]</math>, then, for every partition <math>\sigma</math> of <math>[a, b]</math>, the upper sum <math>U_{\sigma}</math> of <math>f</math> relative to <math>\sigma</math> is equal to <math>k(b - a)</math>, and so is the lower sum. Thus | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

L_{\sigma} = k(b - a) = U_{\sigma}, | |||

</math> | |||

which proves both that <math>f</math> is integrable and that the value of the integral is <math>k(b - a)</math>. | |||

The proof of (4.3) is slightly more difficult and probably most easily obtained by contradiction. Suppose the premise true and the conclusion false. That is, we assume that <math>\int_{a}^{b} f > \int_{a}^{b} g</math>. The definition of integrability asserts that if a function is integrable over an interval, then there exist upper and lower sums Iying arbitrarily close to the definite integral. Therefore, since g is integrable and since ia <math>\int_{a}^{b} g < \int_{a}^{b} f</math> there must exist an upper sum for <math>g</math> which is less than <math>\int_{a}^{b} f</math>. Specifically, there exists a partition <math>\sigma</math> of <math>[a, b]</math> such | |||

that the upper sum of <math>g</math> relative to <math>\sigma</math>, which we shall denote by <math>U_{\sigma}(g)</math>, satisfies the inequality | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{a}^{b} g \leq U_{\sigma}(g) < \int_{a}^{b} f. | |||

</math> | |||

But since <math>f(x) \leq g(x)</math> for every <math>x</math> in <math>[a, b]</math>, the corresponding upper sum of <math>f</math>, denoted <math>U_{\sigma}(f)</math> is less than or equal to <math>U_{\sigma}(g)</math>. Thus we obtain the inequalities | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

U_{\sigma}(f) \leq U_{\sigma}(g) < \int_{a}^{b} f. | |||

</math> | |||

However, every upper sum of <math>f</math> is greater than or equal to the integral <math>\int_{a}^{b} f</math>. Hence we have arrived at a contradiction, and (4.3) is proved. The proofs of (4.2) and (4.5) are given in Appendix B, and that of (4.4) is assigned as a problem at the end of the section. | |||

The additivity property of the integral stated in Theorem (4.2) obviously extends to any finite number of intervals. Thus if <math>\sigma = \{ x_0, . . ., x_n \} </math> is a partition of <math>[a, b]</math> with <math>a = x_0 \leq x_1 \leq ... \leq x_{n} = b</math>, and if <math>f</math> is integrable over each subinterval <math>[x_{i-1}, x_i]</math>, then by repeated application of (4.2) it follows that <math>f</math> is integrable over <math>[a, b]</math> and that | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq4.4.1"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

\int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx = \sum_{i = 1}^{n} \int_{x_{i-1}}^{x_{i}} f(x) dx. | |||

\label{eq4.4.1} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

In Section 3 it was proved that if a function is monotonic on a closed interval, then it is integrable over that interval. Theorem (4.2), as extended in equation (1), increases the scope of this result enormously. For although a function <math>f</math> may not be monotonic on a given interval <math>[a, b]</math>, it is frequently possible to partition <math>[a, b]</math> into subintervals on each of which <math>f</math> is monotonic. It then follows that <math>f</math> is integrable over the entire interval; i.e., <math>\int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx</math> exists. | |||

'''Example''' | |||

For every nonnegative integer <math>n</math> and interval <math>[a, b]</math>, show that the definite integral | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{a}^{b} x^{n} dx | |||

</math> | |||

exists. To say that <math>\int_{a}^{b} x^{n} dx</math> exists is just another way of saying that the function <math>f</math> defined by <math>f(x) = x^n</math> is integrable over <math>[a, b]</math>. We now prove that this is so. For every nonnegative integer <math>n</math>, the function <math>x^n</math> is an increasing function on the interval <math>[0, \infty)</math>, and it is an increasing or a decreasing function on <math>(-\infty, 0]</math> according as <math>n</math> is odd or even. Hence if <math>[a, b]</math> is a subset of <math>[0, \infty)</math> or a subset of <math>(-\infty, 0]</math>, then the function <math>x^n</math> is monotonic on <math>[a, b]</math> and is | |||

therefore integrable over that interval. The remaining possibility is that | |||

<math>a < 0 < b</math>. In this case, <math>x^n</math> is integrable over the intervals <math>[a, 0]</math> and <math>[0, b]</math> separately. It then follows that <math>x^n</math> is integrable over their union, which is <math>[a, b]</math>, and the proof is complete. | |||

Just as Theorem (4.2) was generalized to more than two intervals, Theorem (4.5) can be extended to any finite number of functions. Thus if each one of the functions <math>f_{1}, ..., f_{n}</math> is integrable over <math>[a, b]</math>, then by repeated | |||

applications of (4.5) it follows that the sum <math>f_{1} + ... + f_{n}</math> is integrable over <math>[a, b]</math> and that | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq4.4.2"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

\int_{a}^{b} [f_{1}(x) + ... + f_{n}(x)] dx = \int_{a}^{b} f_{1}(x) dx +... + \int_{a}^{b} f_{n}(x) dx. | |||

\label{eq4.4.2} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

<span id="eq4.4.3"/> | |||

'''Example''' | |||

Consider an arbitrary polynomial | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

p(x) = a_{n}x^{n} + a_{n-1} x^{n - 1} + ... + a_{1}x + a_0 | |||

</math> | |||

and a closed interval <math>[a, b]</math>. Then, for each <math>i = 0,... , n</math>, we know from Example 1 that <math>\int_{a}^{b} x^{i }dx</math> exists. It follows by (4.4) that each function <math>a_{i}x^{i}</math> is integrable over <math>[a, b]</math> and that <math>\int_{a}^{b} a_{i}x^{i}dx = a_{i }\int_{a}^{b} x^{i} dx</math>. We conclude from the preceding | |||

paragraph that the polynomial <math>p(x)</math>, which is the sum of the functions <math>a_{i}x^{i}</math>, is integrable and that | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq4.4.3"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

\int_{a}^{b} p(x) dx = \sum_{i = 0}^{n} a_{i} \int_{a}^{b} x^{i} dx. | |||

\label{eq4.4.3} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

As a concrete example of equation (3), consider the polynomial <math>7x^5 - 3x^3 + x^2 + 3</math>. We have immediately | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{a}^{b} (7x^5 - 3x^3 + x^2 + 3) dx | |||

= 7 \int_{a}^{b} x^5 dx - 3 \int_{a}^{b} x^3 dx + \int_{a}^{b} x^{2} dx + 3 \int_{a}^{b} 1 dx. | |||

</math> | |||

Since we know from (4.1) that <math>\int_{a}^{b} 1 dx = b - a</math>, the last term in the above equation can be replaced by <math>3(b - a)</math>. | |||

Summarizing Examples 1 and 2, we conclude that all polynomials are integrable and that the problem of computing their integrals reduces to the problem of computing the integrals of the positive powers of <math>x</math>. | |||

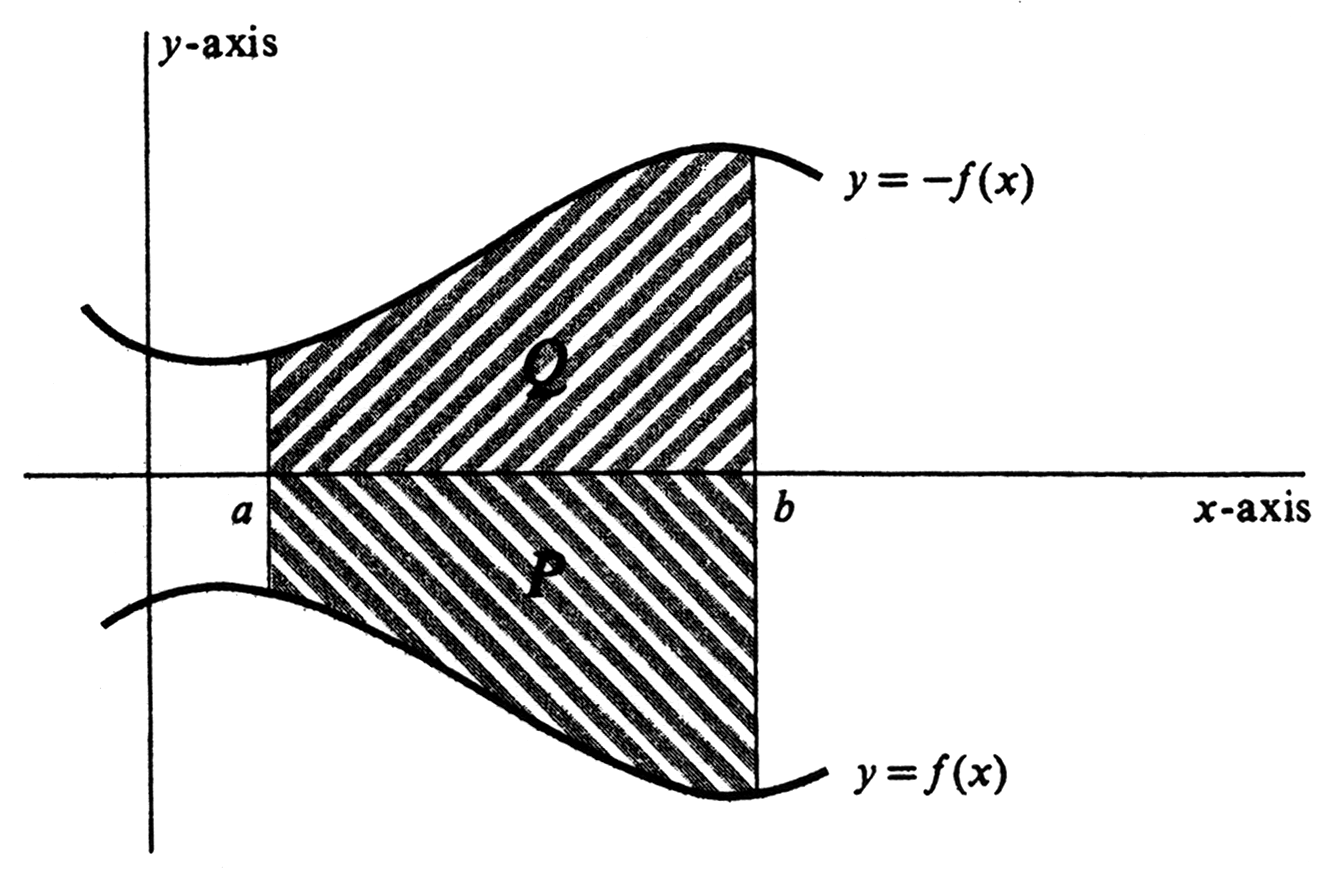

The interpretation of the definite integral as an area will now be generalized to include functions which may take on negative values. To begin with, suppose that a function <math>f</math> is integrable over <math>[a, b]</math> and, in addition, that | |||

<math>f (x) \leq 0</math> for all <math>x</math> in <math>[a, b]</math>. The graphs of both <math>f</math> and <math>-f</math> are drawn | |||

in [[#fig 4.12|Figure]]. As shown in the figure, we denote by <math>P</math> the region consisting of all points <math>(x, y)</math> such that <math>a \leq x \leq b</math> end <math>f(x) \leq y \leq 0</math>, and, similarly, by <math>Q</math> the region defined by <math>a \leq x \leq b</math> and <math>0 \leq y \leq -f(x)</math>. It is obvious that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

area(P) = area(Q). | |||

</math> | |||

<div id="fig 4.12" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig4_12.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

It follows from Theorem (4.4), by taking <math>k = -1</math>, that the function <math>-f</math> is integrable over <math>[a, b]</math> and that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{a}^{b} (-f(x)) dx = - \int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx. | |||

</math> | |||

Since<math>-f(x) \geq 0</math> for every <math>x</math> in <math>[a, b]</math>, we know that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{a}^{b} (-f(x)) dx = area(Q). | |||

</math> | |||

Combining the preceding three equations, we conclude that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{a}^{b} f (x) dx = -area(P). | |||

</math> | |||

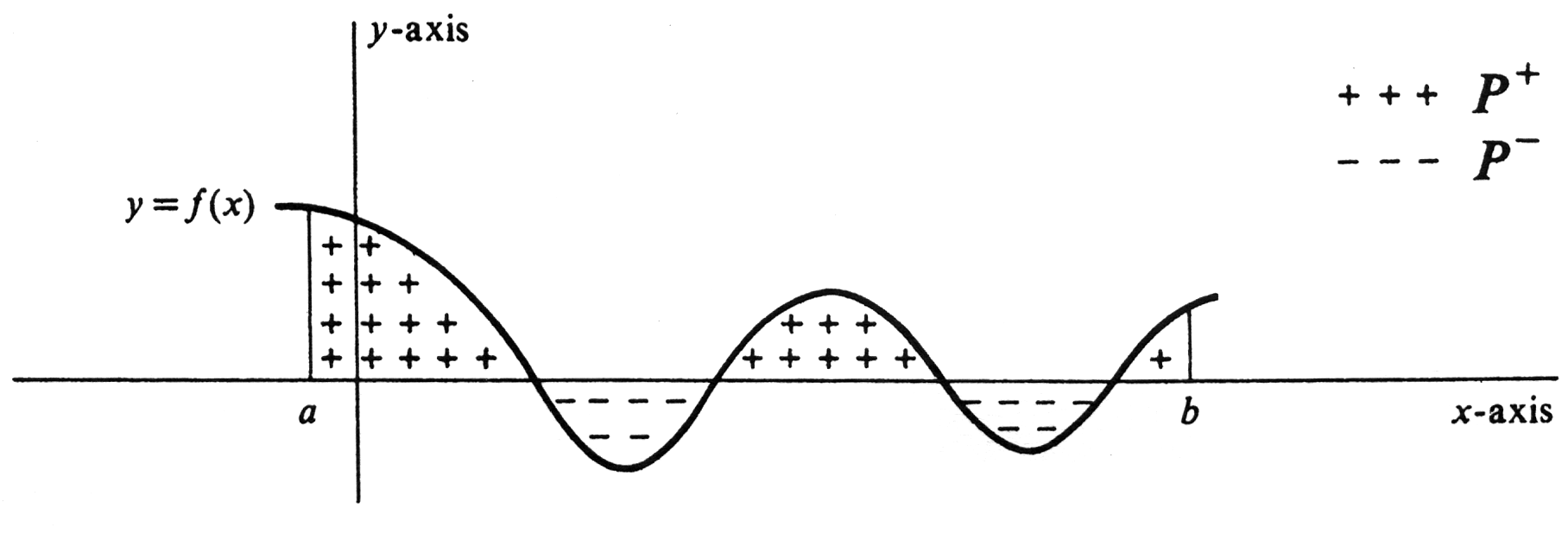

Next, we suppose that <math>f</math> is integrable over <math>[a, b]</math> and takes on both positive and negative values. Specifically, let <math>[a, b]</math> be partitionea by inequalities | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

a = x_0 \leq x_1 \leq ... \leq x_n = b | |||

</math> | |||

so that on each subinterval <math>[x_{i -1}, x_i]</math> the function <math>f</math> is either nonnegative or nonpositive. We denote by <math>P^{+}</math> the set of all points <math>(x, y)</math> such that <math>a \leq x \leq b</math> and <math>0 \leq y \leq f(x)</math>, and by <math>P^{-}</math> the set of all points <math>(x, y)</math> such that <math>a \leq x \leq b</math> | |||

and <math>f(x) \leq y \leq 0</math> (see [[#fig 4.13|Figure]]). It follows from the conclusion of the preceding paragraph and from the additivity of the integral, as generalized in equation (1), that | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-6| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx = area(P^{+}) - area(P^{-}). | |||

</math>|}} | |||

This is the principal geometric interpretation of the integral. | |||

<div id="fig 4.13" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig4_13.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

'''Example''' | |||

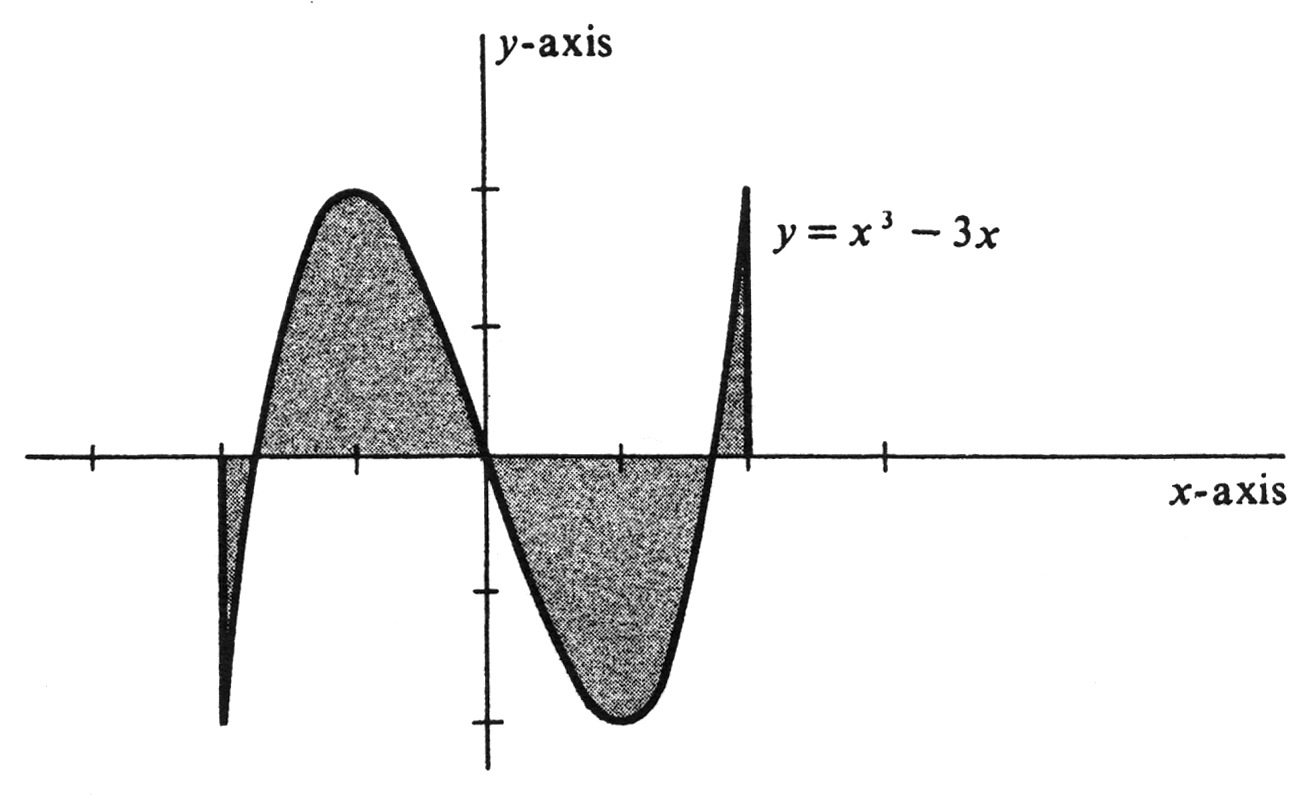

Evaluate <math>\int_{-2}^{2} (x^3 - 3x) dx</math>. The integrand, <math>f(x) = x^3 - 3x</math>, is an an odd function; i.e., the equation <math>f(- x) = - f(x)</math> is satisfied for every <math>x</math>. Its graph, drawn in [[#fig 4.14|Figure]], is therefore symmetric under reflection first about the <math>x</math>-axis and then about the <math>y</math>-axis. It follows that the region <math>P^{+}</math> above the <math>x</math>-axis has the same areas as the region <math>P^{-}</math> below it. | |||

We conclude that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{-2}^{2} (x^3 - 3x) dx = 0. | |||

</math> | |||

<div id="fig 4.14" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig4_14.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

The final topic of this section is an extension of the definition of the integral. Up to this point, <math>\int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx</math> has been defined only if <math>a \leq b</math>. It turns out to be algebraically more convenient to remove this restriction. We do so by decree: If <math>f</math> is integrable over the interval <math>[a, b]</math>, then we now define | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq4.4.4"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

\int_{b}^{a} f(x) dx = - \int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx. | |||

\label{eq4.4.4} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

It is a simple matter to verify that the equations which form the conclusions of Theorems (4.1), (4.4), and (4.5) remain true, in the light of the extended definition of the integral, if <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> are interchanged. Thus | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\int_{a}^{b} k dx &=& k(b - a),\\ | |||

\int_{a}^{b} k f(x)dx &=& k\int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx,\\ | |||

\int_{a}^{b} [f (x) + g(x)] dx &=& \int_{a}^{b} f (x) dx + \int_{a}^{b} g(x) dx, | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

are valid equations regardless of whether <math>a \leq b</math> or <math>b \leq a</math>. | |||

On the other hand, if <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> are interchanged in the conclusion of Theorem (4.3), then the direction of the inequality must be reversed. | |||

Less trivial to verify, but equally important, is the generalized form of (4.2): | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-7|If <math>f</math> is integrable over the smallest closed interoal which contains the numbers <math>a</math>, <math>b</math>, and <math>c</math>, then | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\int_{a}^{b} f(x)dx + \int_{b}^{c} f(x)dx = \int_{a}^{c} f(x)dx. | |||

</math>| | |||

The proof is obtained from (4.2) and the definition (4) by simply checking each of the six possible cases in turn: | |||

# <math>a \leq b \leq c.</math> | |||

# <math>a \leq c \leq b.</math> | |||

#<math>b \leq a \leq c.</math> | |||

#<math>b \leq c \leq a.</math> | |||

#<math>c \leq a \leq b.</math> | |||

#<math>c \leq b \leq a.</math> | |||

The details are tedious, and we omit them.}} | |||

==General references== | |||

{{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | |||

Latest revision as of 22:31, 18 November 2024

If a function [math]f[/math] is integrable over an interval [math][a, b][/math], then in the definite integral

the function [math]f[/math] is called the integrand, and the numbers [math]a[/math] and [math]b[/math] the limits of integration. The basic properties of the definite integral are contained in the following five theorems.

If [math]f (x) = k[/math] for every [math]x[/math] in the interval [math][a, b][/math], then

The function [math]f[/math] is integrable over the intervals [math][a, b][/math] and [math][b, c][/math] if and only if it is integrable over their union [math][a, c][/math]. Furthermore,

If [math]f[/math] and [math]g[/math] are integrable over [math][a, b][/math] and if [math]f (x) \leq g(x)[/math] for every [math]x[/math] in [math][a, b][/math], then

If [math]f[/math] is integrable over [math][a, b][/math] and if [math]k[/math] is any real number, then the product [math]kf[/math] is integrable and

If [math]f[/math] and [math]g[/math] are integrable over [math][a, b][/math], then so is their sum and

None of the proofs of these theorems is deep in the sense of requiring great ingenuity or any techniques beyond the use of least upper bounds and greatest lower bounds. However, they vary considerably in the amount of detail required. The proof of (4.1) is a triviality. For if [math]f[/math] has the constant value [math]k[/math] on the interval [math][a, b][/math], then, for every partition [math]\sigma[/math] of [math][a, b][/math], the upper sum [math]U_{\sigma}[/math] of [math]f[/math] relative to [math]\sigma[/math] is equal to [math]k(b - a)[/math], and so is the lower sum. Thus

which proves both that [math]f[/math] is integrable and that the value of the integral is [math]k(b - a)[/math]. The proof of (4.3) is slightly more difficult and probably most easily obtained by contradiction. Suppose the premise true and the conclusion false. That is, we assume that [math]\int_{a}^{b} f \gt \int_{a}^{b} g[/math]. The definition of integrability asserts that if a function is integrable over an interval, then there exist upper and lower sums Iying arbitrarily close to the definite integral. Therefore, since g is integrable and since ia [math]\int_{a}^{b} g \lt \int_{a}^{b} f[/math] there must exist an upper sum for [math]g[/math] which is less than [math]\int_{a}^{b} f[/math]. Specifically, there exists a partition [math]\sigma[/math] of [math][a, b][/math] such that the upper sum of [math]g[/math] relative to [math]\sigma[/math], which we shall denote by [math]U_{\sigma}(g)[/math], satisfies the inequality

But since [math]f(x) \leq g(x)[/math] for every [math]x[/math] in [math][a, b][/math], the corresponding upper sum of [math]f[/math], denoted [math]U_{\sigma}(f)[/math] is less than or equal to [math]U_{\sigma}(g)[/math]. Thus we obtain the inequalities

However, every upper sum of [math]f[/math] is greater than or equal to the integral [math]\int_{a}^{b} f[/math]. Hence we have arrived at a contradiction, and (4.3) is proved. The proofs of (4.2) and (4.5) are given in Appendix B, and that of (4.4) is assigned as a problem at the end of the section. The additivity property of the integral stated in Theorem (4.2) obviously extends to any finite number of intervals. Thus if [math]\sigma = \{ x_0, . . ., x_n \} [/math] is a partition of [math][a, b][/math] with [math]a = x_0 \leq x_1 \leq ... \leq x_{n} = b[/math], and if [math]f[/math] is integrable over each subinterval [math][x_{i-1}, x_i][/math], then by repeated application of (4.2) it follows that [math]f[/math] is integrable over [math][a, b][/math] and that

In Section 3 it was proved that if a function is monotonic on a closed interval, then it is integrable over that interval. Theorem (4.2), as extended in equation (1), increases the scope of this result enormously. For although a function [math]f[/math] may not be monotonic on a given interval [math][a, b][/math], it is frequently possible to partition [math][a, b][/math] into subintervals on each of which [math]f[/math] is monotonic. It then follows that [math]f[/math] is integrable over the entire interval; i.e., [math]\int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx[/math] exists.

Example

For every nonnegative integer [math]n[/math] and interval [math][a, b][/math], show that the definite integral

exists. To say that [math]\int_{a}^{b} x^{n} dx[/math] exists is just another way of saying that the function [math]f[/math] defined by [math]f(x) = x^n[/math] is integrable over [math][a, b][/math]. We now prove that this is so. For every nonnegative integer [math]n[/math], the function [math]x^n[/math] is an increasing function on the interval [math][0, \infty)[/math], and it is an increasing or a decreasing function on [math](-\infty, 0][/math] according as [math]n[/math] is odd or even. Hence if [math][a, b][/math] is a subset of [math][0, \infty)[/math] or a subset of [math](-\infty, 0][/math], then the function [math]x^n[/math] is monotonic on [math][a, b][/math] and is therefore integrable over that interval. The remaining possibility is that [math]a \lt 0 \lt b[/math]. In this case, [math]x^n[/math] is integrable over the intervals [math][a, 0][/math] and [math][0, b][/math] separately. It then follows that [math]x^n[/math] is integrable over their union, which is [math][a, b][/math], and the proof is complete.

Just as Theorem (4.2) was generalized to more than two intervals, Theorem (4.5) can be extended to any finite number of functions. Thus if each one of the functions [math]f_{1}, ..., f_{n}[/math] is integrable over [math][a, b][/math], then by repeated applications of (4.5) it follows that the sum [math]f_{1} + ... + f_{n}[/math] is integrable over [math][a, b][/math] and that

Example

Consider an arbitrary polynomial

and a closed interval [math][a, b][/math]. Then, for each [math]i = 0,... , n[/math], we know from Example 1 that [math]\int_{a}^{b} x^{i }dx[/math] exists. It follows by (4.4) that each function [math]a_{i}x^{i}[/math] is integrable over [math][a, b][/math] and that [math]\int_{a}^{b} a_{i}x^{i}dx = a_{i }\int_{a}^{b} x^{i} dx[/math]. We conclude from the preceding paragraph that the polynomial [math]p(x)[/math], which is the sum of the functions [math]a_{i}x^{i}[/math], is integrable and that

As a concrete example of equation (3), consider the polynomial [math]7x^5 - 3x^3 + x^2 + 3[/math]. We have immediately

Since we know from (4.1) that [math]\int_{a}^{b} 1 dx = b - a[/math], the last term in the above equation can be replaced by [math]3(b - a)[/math].

Summarizing Examples 1 and 2, we conclude that all polynomials are integrable and that the problem of computing their integrals reduces to the problem of computing the integrals of the positive powers of [math]x[/math]. The interpretation of the definite integral as an area will now be generalized to include functions which may take on negative values. To begin with, suppose that a function [math]f[/math] is integrable over [math][a, b][/math] and, in addition, that [math]f (x) \leq 0[/math] for all [math]x[/math] in [math][a, b][/math]. The graphs of both [math]f[/math] and [math]-f[/math] are drawn in Figure. As shown in the figure, we denote by [math]P[/math] the region consisting of all points [math](x, y)[/math] such that [math]a \leq x \leq b[/math] end [math]f(x) \leq y \leq 0[/math], and, similarly, by [math]Q[/math] the region defined by [math]a \leq x \leq b[/math] and [math]0 \leq y \leq -f(x)[/math]. It is obvious that

It follows from Theorem (4.4), by taking [math]k = -1[/math], that the function [math]-f[/math] is integrable over [math][a, b][/math] and that

Since[math]-f(x) \geq 0[/math] for every [math]x[/math] in [math][a, b][/math], we know that

Combining the preceding three equations, we conclude that

Next, we suppose that [math]f[/math] is integrable over [math][a, b][/math] and takes on both positive and negative values. Specifically, let [math][a, b][/math] be partitionea by inequalities

so that on each subinterval [math][x_{i -1}, x_i][/math] the function [math]f[/math] is either nonnegative or nonpositive. We denote by [math]P^{+}[/math] the set of all points [math](x, y)[/math] such that [math]a \leq x \leq b[/math] and [math]0 \leq y \leq f(x)[/math], and by [math]P^{-}[/math] the set of all points [math](x, y)[/math] such that [math]a \leq x \leq b[/math] and [math]f(x) \leq y \leq 0[/math] (see Figure). It follows from the conclusion of the preceding paragraph and from the additivity of the integral, as generalized in equation (1), that

This is the principal geometric interpretation of the integral.

Example

Evaluate [math]\int_{-2}^{2} (x^3 - 3x) dx[/math]. The integrand, [math]f(x) = x^3 - 3x[/math], is an an odd function; i.e., the equation [math]f(- x) = - f(x)[/math] is satisfied for every [math]x[/math]. Its graph, drawn in Figure, is therefore symmetric under reflection first about the [math]x[/math]-axis and then about the [math]y[/math]-axis. It follows that the region [math]P^{+}[/math] above the [math]x[/math]-axis has the same areas as the region [math]P^{-}[/math] below it. We conclude that

The final topic of this section is an extension of the definition of the integral. Up to this point, [math]\int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx[/math] has been defined only if [math]a \leq b[/math]. It turns out to be algebraically more convenient to remove this restriction. We do so by decree: If [math]f[/math] is integrable over the interval [math][a, b][/math], then we now define

It is a simple matter to verify that the equations which form the conclusions of Theorems (4.1), (4.4), and (4.5) remain true, in the light of the extended definition of the integral, if [math]a[/math] and [math]b[/math] are interchanged. Thus

are valid equations regardless of whether [math]a \leq b[/math] or [math]b \leq a[/math].

On the other hand, if [math]a[/math] and [math]b[/math] are interchanged in the conclusion of Theorem (4.3), then the direction of the inequality must be reversed.

Less trivial to verify, but equally important, is the generalized form of (4.2):

If [math]f[/math] is integrable over the smallest closed interoal which contains the numbers [math]a[/math], [math]b[/math], and [math]c[/math], then

The proof is obtained from (4.2) and the definition (4) by simply checking each of the six possible cases in turn:

- [math]a \leq b \leq c.[/math]

- [math]a \leq c \leq b.[/math]

- [math]b \leq a \leq c.[/math]

- [math]b \leq c \leq a.[/math]

- [math]c \leq a \leq b.[/math]

- [math]c \leq b \leq a.[/math]

The details are tedious, and we omit them.

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.