guide:A8f4ffd76f: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="d-none"><math> | |||

\newcommand{\ex}[1]{\item } | |||

\newcommand{\sx}{\item} | |||

\newcommand{\x}{\sx} | |||

\newcommand{\sxlab}[1]{} | |||

\newcommand{\xlab}{\sxlab} | |||

\newcommand{\prov}[1] {\quad #1} | |||

\newcommand{\provx}[1] {\quad \mbox{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\intext}[1]{\quad \mbox{#1} \quad} | |||

\newcommand{\R}{\mathrm{\bf R}} | |||

\newcommand{\Q}{\mathrm{\bf Q}} | |||

\newcommand{\Z}{\mathrm{\bf Z}} | |||

\newcommand{\C}{\mathrm{\bf C}} | |||

\newcommand{\dt}{\textbf} | |||

\newcommand{\goesto}{\rightarrow} | |||

\newcommand{\ddxof}[1]{\frac{d #1}{d x}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddx}{\frac{d}{dx}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddt}{\frac{d}{dt}} | |||

\newcommand{\dydx}{\ddxof y} | |||

\newcommand{\nxder}[3]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{d{#3}^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\deriv}[2]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{dx^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\dist}{\mathrm{distance}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccot}{\mathrm{arccot\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccsc}{\mathrm{arccsc\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsec}{\mathrm{arcsec\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arctanh}{\mathrm{arctanh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsinh}{\mathrm{arcsinh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccosh}{\mathrm{arccosh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\sech}{\mathrm{sech\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\csch}{\mathrm{csch\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\conj}[1]{\overline{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb} | |||

</math></div> | |||

In this section we shall define and study the elementary properties of two real-valued functions, the sine and the cosine, abbreviated <math>\sin</math> and <math>\cos</math>, respectively. Both functions have as domain the entire set of all real numbers, and, as we shall see in Section 2, both are differentiable functions. | |||

The definitions will be made in terms of what is called arc length, by which is meant the distance from one point on a curve to another measured along the curve. This is a new concept, for although we have defined the straight-line distance between two points on page 11, we have not yet treated distance along a curve. Actually we shall postpone the discussion of arc length in general to Section 2 of Chapter 10 because here we need it only for distance along a circle, in fact, only along the particular circle <math>C</math> which is the graph of the equation <math>x^2 + y^2 = 1</math> in the <math>xy</math>-plane. However, we shall assume that the idea of distance along this curve is understood. For example, we assume the familiar fact that the arc length of the whole circle <math>C</math>, i.e., its circumference, is equal to <math>2\pi</math>. | |||

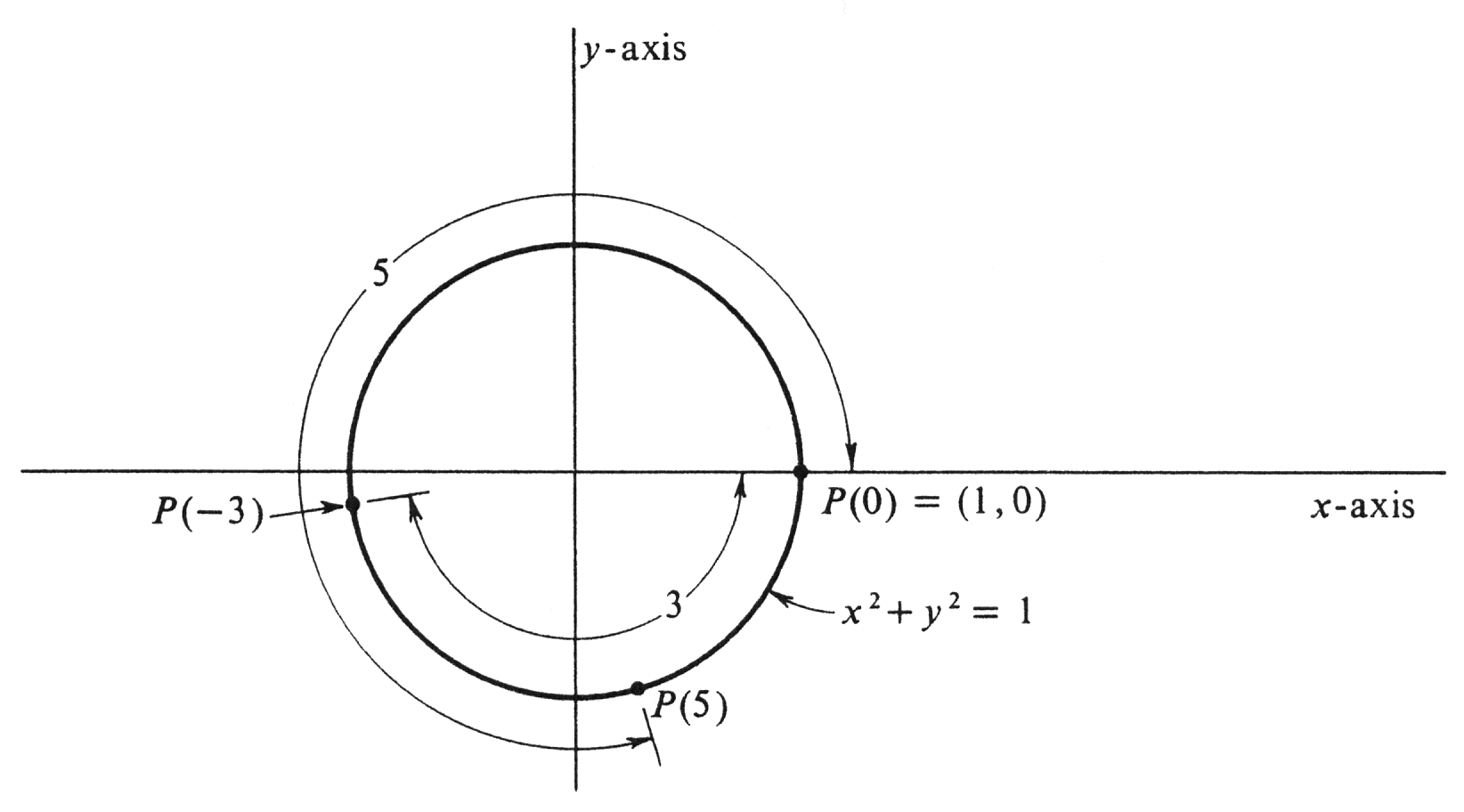

Let <math>t</math> be an arbitrary positive real number. We denote by <math>P(t)</math> the point on the | |||

circle <math>C</math> whose distance from the fixed point (1, 0) along <math>C</math> in the counterclockwise direction is equal to <math>t</math>. Intuitively, we take a piece of string of length <math>t</math>, fasten one end at (1, 0), and wrap the string counterclockwise around <math>C</math>. Then <math>P(t)</math> is the point on the circle to which the other end of the string reaches. Next, for every negative number <math>t</math>, let <math>P(t)</math> be the point on <math>C</math> whose distance from the same fixed point (1, 0) along the curve in the clockwise direction is equal to <math>-t</math>. That is, this time we wrap the string in the opposite direction. Finally, for <math>t = 0</math>, we set <math>P(0) = (1,0)</math>. The definition | |||

is illustrated in [[#fig 6.1|Figure]]. Thus, to every real number <math>t</math>, we have assigned a point <math>P(t)</math> which is an ordered pair of real numbers. Note that, because the circumference of the circle <math>C</math> is <math>2\pi</math>, it follows that | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq6.1.1"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

P(t + 2\pi) = P(t), | |||

\label{eq6.1.1} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

for every real number <math>t</math>. | |||

<div id="fig 6.1" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig6_1.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

The cosine and sine are now defined as follows: <math>\cos(t)</math> is the <math>x</math>-coordinate of <math>P(t)</math>, and <math>\sin(t)</math> is the <math>y</math>-coordinate. More briefly, we write <math>\cos t</math> and <math>\sin t</math>. Thus | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

P(t) = (\cos t, \sin t). | |||

</math> | |||

For example, from [[#fig 6.1|Figure]], in which <math>P(5)</math> is seen to be in the fourth quadrant, we may | |||

conclude that <math>\cos 5</math> is positive and that <math>\sin 5</math> is negative. It is clear geometrically that, if the | |||

difference between two real numbers <math>t</math> and a is small, then the point <math>P(t)</math> is close to the point | |||

<math>P(a)</math> and hence the differences between their corresponding coordinates are small. More precisely, both <math>| \cos t - \cos a |</math> and <math>| \sin t - \sin a|</math> can be made arbitrarily small by choosing <math>|t - a|</math> sufficiently small. It follows that the cosine and the sine are eontinuous functions. Their | |||

common domain is the set of all real numbers. | |||

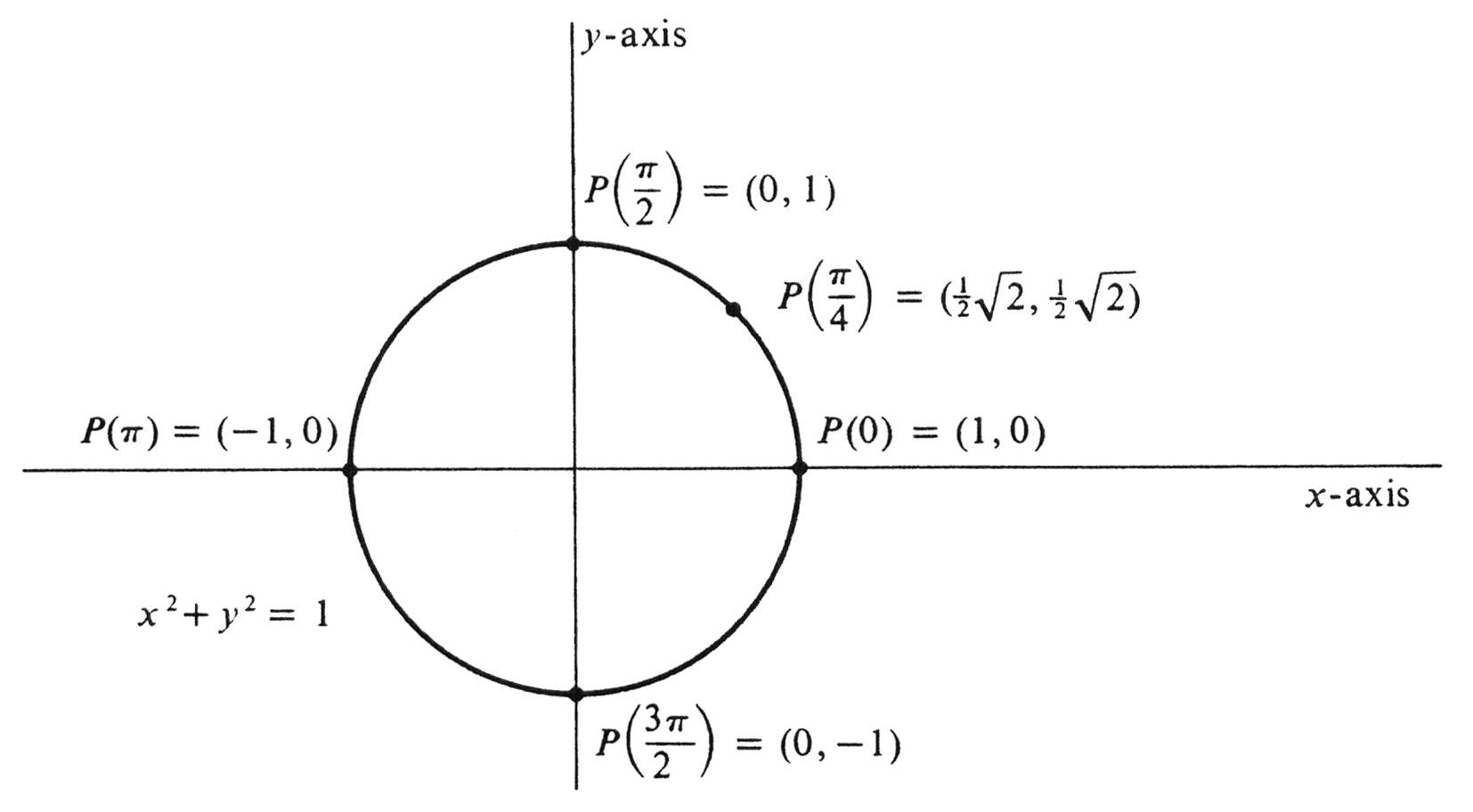

For certain values of <math>t</math> which are simple fractions of the total eircumference <math>2\pi</math>, it is easy to | |||

locate the point <math>P(t)</math> on the circle and then to read off the coordinates <math>\cos t</math> and <math>\sin t</math>. For example (see [[#fig 6.2|Figure]]), | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

P(0) &=& (1,0),\\ | |||

P \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{4} \Bigr) &=& (\frac{1}{2} \sqrt2, \frac{1}{2} \sqrt2),\\ | |||

P \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr) &=& (0, 1),\\ | |||

P(\pi) &=& (-1, 0),\\ | |||

P \Bigl(\frac{3\pi}{2}\Bigr) &=& (0, -1), | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

from which it follows at once that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\cos 0 &=& 1 \;\mbox{and}\; \sin 0 = 0, \\ | |||

\cos \frac{\pi}{4} &=& \sin \frac{\pi}{4} = \frac{1}{2} \sqrt2,\\ | |||

\cos \frac{\pi}{2} &=& 0 \;\mbox{and}\; \sin \frac{\pi}{2} = 1, \\ | |||

\cos \pi &=& -1 \;\mbox{and}\; \sin \pi = 0, \\ | |||

\cos \frac{3\pi}{2} &=& 0 \;\mbox{and}\; \sin \frac{3\pi}{2} = -1, | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

The reader should be thoroughly familiar with all these values---not by sheer memory, | |||

but from an understanding of <math>P(t)</math> and its location on the circle <math>C</math>. | |||

<div id="fig 6.2" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig6_2.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

Most of the important properties of the functions <math>\cos</math> and <math>\sin</math> can be expressed in a few equations called trigonometric identities. Some of these are obvious from the definition of <math>P(t)</math>. To begin with, it follows from (1) that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

(\cos(t + 2\pi), \sin(t + 2\pi)) = P(t + 2\pi) = P(t) = (\cos t, \sin t), | |||

</math> | |||

and so | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-1| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{array}{l} | |||

\cos(t + 2\pi) = \cos t \\ | |||

\sin(t + 2\pi) = \sin t | |||

\end{array} | |||

\left\}\; \mbox{for every real number}\; t. | |||

\right . | |||

</math>|}} | |||

The property of <math>\cos</math> and <math>\sin</math> stated in these two equations is expressed in words by saying that | |||

<math>\cos</math> and <math>\sin</math> are '''periodic functions''' with '''period''' <math>2\pi</math>. That is, each time the value of the variable is increased by <math>2\pi</math>, the value of each function is repeated. | |||

Next, since <math>P(t)</math> lies on the circle defined by <math>x^2 + y^2 = 1</math>, the coordinates of <math>P(t)</math> must satisfy this equation. Hence | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-2| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

(\cos t)^2 + (\sin t)^2 = 1, \;\;\;\mbox{for every real number}\; t. | |||

</math>|}} | |||

There is a strong tradition for abbreviating <math>(\cos t)^n</math> and <math>(\sin t)^n</math> by <math>\cos^{n}t</math> and <math>\sin^{n}t</math>, respectively, provided <math>n</math> is a positive integer. [However, one ''never'' writes <math>\sin^{-1}t</math> for <math>(\sin t)^{-1}</math>.] As a result, (1.2) is usually written | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\cos^{2} t + \sin^{2} t = 1. | |||

</math> | |||

The third basic property of <math>\cos</math> and <math>\sin</math> comes from the relation between <math>P(t) = (\cos t, \sin t)</math> and <math>P(-t) = (\cos(-t), \sin(-t))</math>. It is not hard to see that the difference between measuring the arc length <math>|t|</math> in the counterclockwise direction from (1, 0) and measuring the same distance in the clockwise direction will be only a difference of sign in the <math>y</math>-coordinate of <math>P(t)</math>. That is, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

P(-t) = (\cos(-t), \sin(-t)) = (\cos t, -\sin t). | |||

</math> | |||

It follows that | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-3| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{array}{l} | |||

\cos(- t) = \cos t \\ | |||

\sin(- t) = - \sin t | |||

\end{array} | |||

\} \; \mbox{for every real number $t$.} | |||

</math>|}} | |||

Thus the cosine is an even function, and the sine is an odd function (see pages 90 and 92). | |||

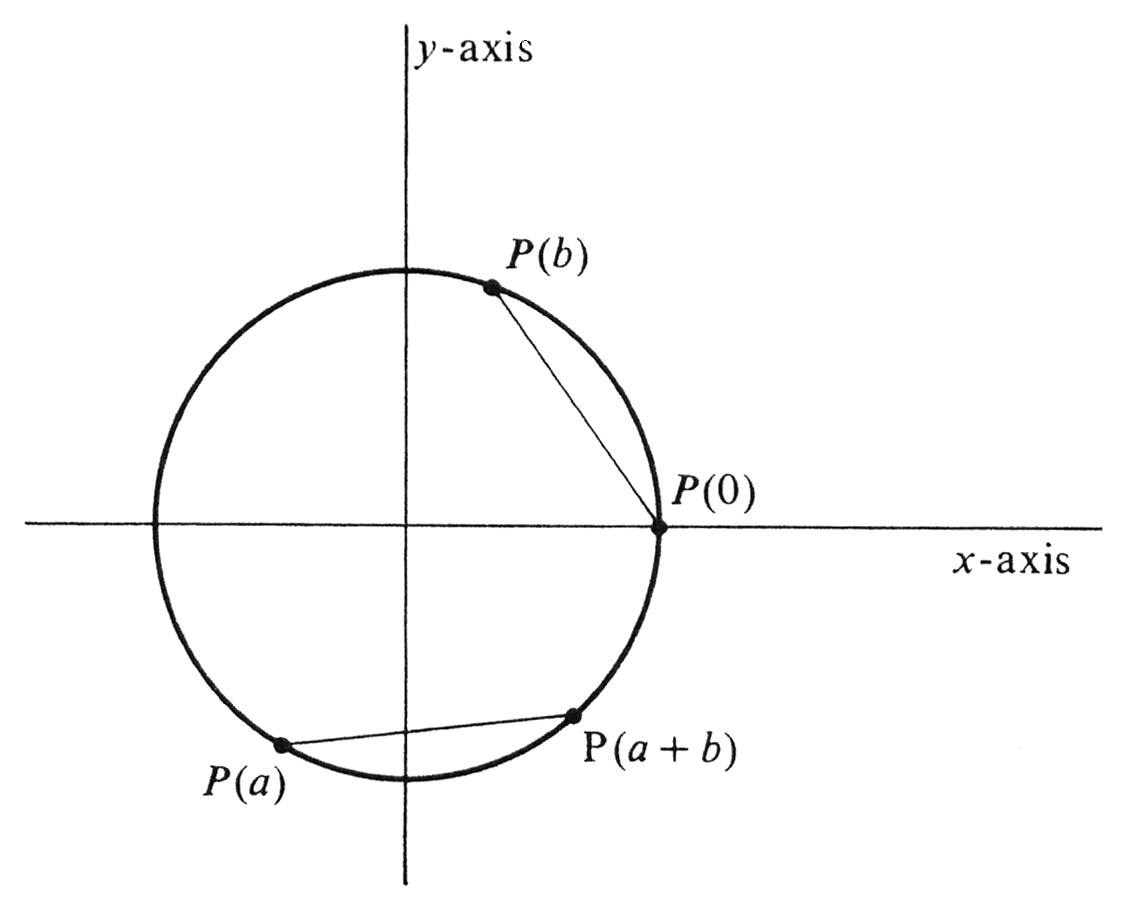

If <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> are any two real numbers, what can we say about the relative positions of the points | |||

<math>P(a)</math>, <math>P(b)</math> and <math>P(a + b)</math> on the circle <math>C</math> defined by <math>x^2 + y^2 = 1</math> ? lt follows from the definition of <math>P(t)</math> that the point <math>P(a + b)</math> is obtained by moving from <math>P(0) = (1, 0)</math> a distance <math>|a + b|</math> along <math>C</math> counterclockwise or clockwise according as <math>a + b</math> is positive or negative. However, it is important to realize that <math>P(a + b)</math> can be reached in two steps another way: First, move from <math>P(0)</math> a distance <math>|a|</math> along <math>C</math>, counterclockwise or clockwise according as <math>a</math> is positive or negative. This move will take us to <math>P(a)</math>. Second, move from <math>P(a)</math> a distance <math>|b|</math> along <math>C</math>, counterclockwise if <math>b</math> is positive and clockwise if <math>b</math> is negative. By examining the different cases--- <math>a > 0</math> and <math>b > 0</math>, then <math>a < 0</math> and <math>b > 0</math>, etc.---one can verify that the final point reached in these two steps is <math>P(a + b)</math>. Note, however, that in the | |||

second step we move from <math>P(a)</math> to <math>P(a + b)</math> in exactly the same way that we would move from | |||

<math>P(0)</math> to <math>P(b)</math> according to the definition of <math>P(b)</math>---by moving along <math>C</math> the same distance and in the same direction. Thus the distance moved along the circle from <math>P(a)</math> to <math>P(a + b)</math> is equal to the distance moved from <math>P(0)</math> to <math>P(b)</math>. It follows that the straight-line distances are the same, too. That is, ''the straight-line distance between <math>P(a + b)</math> and <math>P(a)</math> is equal to the straight-line distance between <math>P(b)</math> and <math>P(0)</math>.'' This important fact is illustrated in [[#fig 6.3|Figure]]. | |||

<div id="fig 6.3" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig6_3.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

We can now derive a formula for the cosine of the difference of two numbers, <math>\cos(c-d)</math>, in terms of the cosines and sines of <math>c</math> and <math>d</math>. Let <math>a = d</math> and <math>b = c - d</math>. Then <math>a + b = c</math>, and it follows directly from the conclusion of the preceding paragraph that the straight-line distance between <math>P(c)</math> and <math>P(d)</math> is equal to the straight-line distance between <math>P(c - d)</math> and (1, 0). But | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

P(c) &=& (\cos c, \sin c),\\ | |||

P(d) &=& (\cos d, \sin d),\\ | |||

P(c-d) &=& (\cos (c-d), \sin (c-d)). | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

Hence by the formula for the distance between two points, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\sqrt{(\cos c - \cos d)^2 + (\sin c - \sin d)^2} | |||

= \sqrt{(\cos (c - d) - 1)^2 + (\sin (c - d) - 0)^2}. | |||

</math> | |||

Squaring both sides and multiplying out, we get | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

&&\cos^{2}c - 2 \cos c \cos d + \cos^{2}d + \sin^{2}c - 2 \sin c \sin d + \sin^{2}d\\ | |||

&&= \cos^{2}(c - d) - 2 \cos(c - d) + 1 + \sin^{2}(c - d). | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

This equation can be greatly simplified by use of the formula <math>\cos^{2}t + \sin^{2}t = 1</math> three times. The result is | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

2 - 2 \cos c \cos d - 2 \sin c \sin d = 2 - 2 \cos(c - d), | |||

</math> | |||

from which follows the identity | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-4| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{array}{c} | |||

\cos(c - d) = \cos c \cos d + \sin c \sin d, \\ | |||

\; \mbox{for all real numbers $c$ and $d$.} | |||

\end{array} | |||

</math>|}} | |||

A similar formula for <math>\cos(c + d)</math> can be obtained easily from (1.3) and (1.4). We have | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\cos(c + d) = \cos(c - (-d)) = \cos c \cos(-d) + \sin c \sin(-d). | |||

</math> | |||

Since <math>\cos(-d) = \cos d</math>, and <math>\sin(-d) = -\sin d</math>, we get | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-5| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{array}{c} | |||

\cos(c + d) = \cos c \cos d - \sin c \sin d, \\ | |||

\;\mbox{for all real numbers $c$ and $d$.} | |||

\end{array} | |||

</math>|}} | |||

Taking <math>c = \frac{\pi}{2}</math> in (1.4), we get <math> \cos \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2} - d \Bigr) = \cos \frac{\pi}{2} \cos d + \sin \frac{\pi}{2} \sin d</math>. Since <math>\cos \frac{\pi}{2} = 0</math> and <math>\sin \frac{\pi}{2} = 1</math>, the result is the useful equation <math>\cos \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2} - d \Bigr) = \sin d</math>. This equation implies its mate. If we write it letting <math>d = \frac{\pi}{2} - a</math>, then <math>\frac{\pi}{2} - d = a</math> and we obtain <math>\cos a = \sin \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2} - a\Bigr)</math>. Thus we have proved the symmetric pair of identities | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-6| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{array}{l} | |||

\cos \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2} - a\Bigr) = \sin a \\ | |||

\sin \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2} - a\Bigr) = \cos a | |||

\end{array} | |||

\} \;\mbox{for every real number $a$.} | |||

</math>|}} | |||

The remaining two identities are the formulas for the sine of the sum and difference of two numbers. The first follows easily from (1.4) and (1.6): | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\sin (a + b) &=& \cos \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2} - (a + b) \Bigr) = \cos \Bigl(\Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2} -a\Bigr) - b\Bigr)\\ | |||

&=& \cos \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2} -a\Bigr) \cos b + \sin \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2} - a\Bigr) \sin b \\ | |||

&=& \sin a \cos b + \cos a \sin b. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

Thence, by (1.3), | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\sin(a-b) &=& \sin(a + (-b)) \\ | |||

&=& \sin a \cos(-b) + \cos a \sin(-b) \\ | |||

&=& \sin a \cos b - \cos a \sin b. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

We write these together in the formula | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-7| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{array}{c} | |||

\sin(a \pm b) = \sin a \cos b \pm \cos a \sin b, \\ | |||

\mbox{for all real numbers $a$ and $b$}. | |||

\end{array} | |||

</math>|}} | |||

An alternative approach to the trigonometric functions is made with a domain of angles instead | |||

of real numbers. We shall show that the two approaches are in no way contradictory. | |||

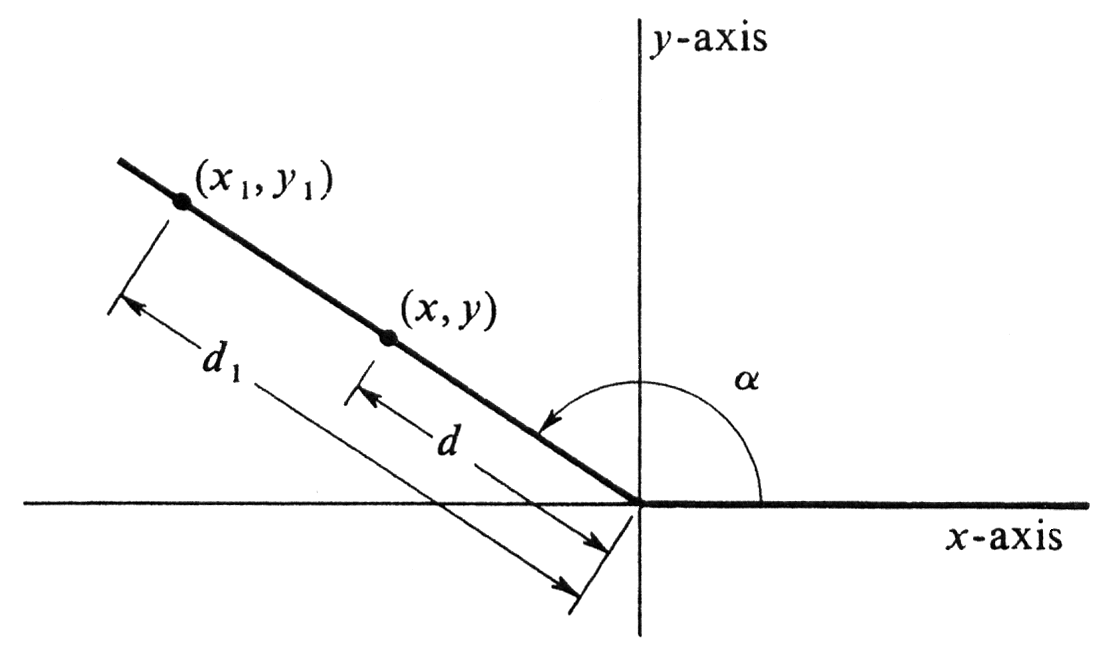

It is assumed that the reader knows what an angle is and what its initial side, its terminal side, and its vertex are. An angle <math>\alpha</math> is said to be in standard position on a Cartesian grid if it has its vertex at the origin and its initial side lies along the positive <math>x</math>-axis. If any point, excluding the vertex, on the terminal side is chosen, it has an abscissa <math>x</math> and an ordinate <math>y</math> and lies at a distance <math>d</math> from the origin. Although each point on the terminal side has its <math>x</math>, its <math>y</math>, and its <math>d</math>, it is easy to see that the ratios <math>\frac{x}{d}</math> and <math>\frac{y}{d}</math> are independent of the choice of the point, i.e., in [[#fig 6.4|Figure]] we have <math>\frac{x}{d} = \frac{x_1}{d_1}</math> and <math>\frac{y}{d} = \frac{y_1}{d_1}</math>. | |||

<div id="fig 6.4" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig6_4.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

Since the location of the terminal side depends on the angle, each of these ratios is a function of | |||

the angle and we define the cosine of <math>\alpha</math> to be <math>\frac{x}{d}</math> and the sine of <math>\alpha</math> to be <math>\frac{y}{d}</math>. Since we may choose any point (not the origin) on the terminal side, we could simplify the process by choosing the point where | |||

<math>d = 1</math>. This, of course, is the point where the terminal side euts the eirele with equation <math>x^2 + | |||

y^2 = 1</math>. Then <math>\cos \alpha</math> is the abscissa of that point and <math>\sin a</math> its ordinate. Hence in many ways the two approaches are the same. | |||

We have not yet mentioned units for measuring angles. If we piek a unit to agree with the are | |||

length, we would have exact agreement: The cosine of an angle of <math>u</math> such units is equal to the | |||

cosine of the real number <math>u</math> and the sine of an angle of <math>u</math> sueh units is equal to the sine of the | |||

real number <math>u</math>. This unit is ealled the '''radian''' and it should be obvious that there are <math>2\pi</math> radians in an angle of one revolution. Another unit, probably more familiar to the reader, is the '''degree,''' which is <math>\frac{1}{360}</math> of a revolution and <math>\frac{\pi}{180}</math> of a radian. Thus the cosine of an angle of <math>d</math> degrees is equal to the cosine of the real number <math>\frac{\pi d}{180}</math>. | |||

==General references== | |||

{{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | |||

Latest revision as of 19:46, 19 November 2024

In this section we shall define and study the elementary properties of two real-valued functions, the sine and the cosine, abbreviated [math]\sin[/math] and [math]\cos[/math], respectively. Both functions have as domain the entire set of all real numbers, and, as we shall see in Section 2, both are differentiable functions. The definitions will be made in terms of what is called arc length, by which is meant the distance from one point on a curve to another measured along the curve. This is a new concept, for although we have defined the straight-line distance between two points on page 11, we have not yet treated distance along a curve. Actually we shall postpone the discussion of arc length in general to Section 2 of Chapter 10 because here we need it only for distance along a circle, in fact, only along the particular circle [math]C[/math] which is the graph of the equation [math]x^2 + y^2 = 1[/math] in the [math]xy[/math]-plane. However, we shall assume that the idea of distance along this curve is understood. For example, we assume the familiar fact that the arc length of the whole circle [math]C[/math], i.e., its circumference, is equal to [math]2\pi[/math]. Let [math]t[/math] be an arbitrary positive real number. We denote by [math]P(t)[/math] the point on the circle [math]C[/math] whose distance from the fixed point (1, 0) along [math]C[/math] in the counterclockwise direction is equal to [math]t[/math]. Intuitively, we take a piece of string of length [math]t[/math], fasten one end at (1, 0), and wrap the string counterclockwise around [math]C[/math]. Then [math]P(t)[/math] is the point on the circle to which the other end of the string reaches. Next, for every negative number [math]t[/math], let [math]P(t)[/math] be the point on [math]C[/math] whose distance from the same fixed point (1, 0) along the curve in the clockwise direction is equal to [math]-t[/math]. That is, this time we wrap the string in the opposite direction. Finally, for [math]t = 0[/math], we set [math]P(0) = (1,0)[/math]. The definition is illustrated in Figure. Thus, to every real number [math]t[/math], we have assigned a point [math]P(t)[/math] which is an ordered pair of real numbers. Note that, because the circumference of the circle [math]C[/math] is [math]2\pi[/math], it follows that

for every real number [math]t[/math].

The cosine and sine are now defined as follows: [math]\cos(t)[/math] is the [math]x[/math]-coordinate of [math]P(t)[/math], and [math]\sin(t)[/math] is the [math]y[/math]-coordinate. More briefly, we write [math]\cos t[/math] and [math]\sin t[/math]. Thus

For example, from Figure, in which [math]P(5)[/math] is seen to be in the fourth quadrant, we may conclude that [math]\cos 5[/math] is positive and that [math]\sin 5[/math] is negative. It is clear geometrically that, if the difference between two real numbers [math]t[/math] and a is small, then the point [math]P(t)[/math] is close to the point [math]P(a)[/math] and hence the differences between their corresponding coordinates are small. More precisely, both [math]| \cos t - \cos a |[/math] and [math]| \sin t - \sin a|[/math] can be made arbitrarily small by choosing [math]|t - a|[/math] sufficiently small. It follows that the cosine and the sine are eontinuous functions. Their common domain is the set of all real numbers. For certain values of [math]t[/math] which are simple fractions of the total eircumference [math]2\pi[/math], it is easy to locate the point [math]P(t)[/math] on the circle and then to read off the coordinates [math]\cos t[/math] and [math]\sin t[/math]. For example (see Figure),

from which it follows at once that

The reader should be thoroughly familiar with all these values---not by sheer memory,

but from an understanding of [math]P(t)[/math] and its location on the circle [math]C[/math].

Most of the important properties of the functions [math]\cos[/math] and [math]\sin[/math] can be expressed in a few equations called trigonometric identities. Some of these are obvious from the definition of [math]P(t)[/math]. To begin with, it follows from (1) that

and so

The property of [math]\cos[/math] and [math]\sin[/math] stated in these two equations is expressed in words by saying that [math]\cos[/math] and [math]\sin[/math] are periodic functions with period [math]2\pi[/math]. That is, each time the value of the variable is increased by [math]2\pi[/math], the value of each function is repeated. Next, since [math]P(t)[/math] lies on the circle defined by [math]x^2 + y^2 = 1[/math], the coordinates of [math]P(t)[/math] must satisfy this equation. Hence

There is a strong tradition for abbreviating [math](\cos t)^n[/math] and [math](\sin t)^n[/math] by [math]\cos^{n}t[/math] and [math]\sin^{n}t[/math], respectively, provided [math]n[/math] is a positive integer. [However, one never writes [math]\sin^{-1}t[/math] for [math](\sin t)^{-1}[/math].] As a result, (1.2) is usually written

The third basic property of [math]\cos[/math] and [math]\sin[/math] comes from the relation between [math]P(t) = (\cos t, \sin t)[/math] and [math]P(-t) = (\cos(-t), \sin(-t))[/math]. It is not hard to see that the difference between measuring the arc length [math]|t|[/math] in the counterclockwise direction from (1, 0) and measuring the same distance in the clockwise direction will be only a difference of sign in the [math]y[/math]-coordinate of [math]P(t)[/math]. That is,

It follows that

Thus the cosine is an even function, and the sine is an odd function (see pages 90 and 92). If [math]a[/math] and [math]b[/math] are any two real numbers, what can we say about the relative positions of the points [math]P(a)[/math], [math]P(b)[/math] and [math]P(a + b)[/math] on the circle [math]C[/math] defined by [math]x^2 + y^2 = 1[/math] ? lt follows from the definition of [math]P(t)[/math] that the point [math]P(a + b)[/math] is obtained by moving from [math]P(0) = (1, 0)[/math] a distance [math]|a + b|[/math] along [math]C[/math] counterclockwise or clockwise according as [math]a + b[/math] is positive or negative. However, it is important to realize that [math]P(a + b)[/math] can be reached in two steps another way: First, move from [math]P(0)[/math] a distance [math]|a|[/math] along [math]C[/math], counterclockwise or clockwise according as [math]a[/math] is positive or negative. This move will take us to [math]P(a)[/math]. Second, move from [math]P(a)[/math] a distance [math]|b|[/math] along [math]C[/math], counterclockwise if [math]b[/math] is positive and clockwise if [math]b[/math] is negative. By examining the different cases--- [math]a \gt 0[/math] and [math]b \gt 0[/math], then [math]a \lt 0[/math] and [math]b \gt 0[/math], etc.---one can verify that the final point reached in these two steps is [math]P(a + b)[/math]. Note, however, that in the second step we move from [math]P(a)[/math] to [math]P(a + b)[/math] in exactly the same way that we would move from [math]P(0)[/math] to [math]P(b)[/math] according to the definition of [math]P(b)[/math]---by moving along [math]C[/math] the same distance and in the same direction. Thus the distance moved along the circle from [math]P(a)[/math] to [math]P(a + b)[/math] is equal to the distance moved from [math]P(0)[/math] to [math]P(b)[/math]. It follows that the straight-line distances are the same, too. That is, the straight-line distance between [math]P(a + b)[/math] and [math]P(a)[/math] is equal to the straight-line distance between [math]P(b)[/math] and [math]P(0)[/math]. This important fact is illustrated in Figure.

We can now derive a formula for the cosine of the difference of two numbers, [math]\cos(c-d)[/math], in terms of the cosines and sines of [math]c[/math] and [math]d[/math]. Let [math]a = d[/math] and [math]b = c - d[/math]. Then [math]a + b = c[/math], and it follows directly from the conclusion of the preceding paragraph that the straight-line distance between [math]P(c)[/math] and [math]P(d)[/math] is equal to the straight-line distance between [math]P(c - d)[/math] and (1, 0). But

Hence by the formula for the distance between two points,

Squaring both sides and multiplying out, we get

This equation can be greatly simplified by use of the formula [math]\cos^{2}t + \sin^{2}t = 1[/math] three times. The result is

from which follows the identity

A similar formula for [math]\cos(c + d)[/math] can be obtained easily from (1.3) and (1.4). We have

Since [math]\cos(-d) = \cos d[/math], and [math]\sin(-d) = -\sin d[/math], we get

Taking [math]c = \frac{\pi}{2}[/math] in (1.4), we get [math] \cos \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2} - d \Bigr) = \cos \frac{\pi}{2} \cos d + \sin \frac{\pi}{2} \sin d[/math]. Since [math]\cos \frac{\pi}{2} = 0[/math] and [math]\sin \frac{\pi}{2} = 1[/math], the result is the useful equation [math]\cos \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2} - d \Bigr) = \sin d[/math]. This equation implies its mate. If we write it letting [math]d = \frac{\pi}{2} - a[/math], then [math]\frac{\pi}{2} - d = a[/math] and we obtain [math]\cos a = \sin \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2} - a\Bigr)[/math]. Thus we have proved the symmetric pair of identities

The remaining two identities are the formulas for the sine of the sum and difference of two numbers. The first follows easily from (1.4) and (1.6):

Thence, by (1.3),

We write these together in the formula

An alternative approach to the trigonometric functions is made with a domain of angles instead of real numbers. We shall show that the two approaches are in no way contradictory. It is assumed that the reader knows what an angle is and what its initial side, its terminal side, and its vertex are. An angle [math]\alpha[/math] is said to be in standard position on a Cartesian grid if it has its vertex at the origin and its initial side lies along the positive [math]x[/math]-axis. If any point, excluding the vertex, on the terminal side is chosen, it has an abscissa [math]x[/math] and an ordinate [math]y[/math] and lies at a distance [math]d[/math] from the origin. Although each point on the terminal side has its [math]x[/math], its [math]y[/math], and its [math]d[/math], it is easy to see that the ratios [math]\frac{x}{d}[/math] and [math]\frac{y}{d}[/math] are independent of the choice of the point, i.e., in Figure we have [math]\frac{x}{d} = \frac{x_1}{d_1}[/math] and [math]\frac{y}{d} = \frac{y_1}{d_1}[/math].

Since the location of the terminal side depends on the angle, each of these ratios is a function of the angle and we define the cosine of [math]\alpha[/math] to be [math]\frac{x}{d}[/math] and the sine of [math]\alpha[/math] to be [math]\frac{y}{d}[/math]. Since we may choose any point (not the origin) on the terminal side, we could simplify the process by choosing the point where [math]d = 1[/math]. This, of course, is the point where the terminal side euts the eirele with equation [math]x^2 + y^2 = 1[/math]. Then [math]\cos \alpha[/math] is the abscissa of that point and [math]\sin a[/math] its ordinate. Hence in many ways the two approaches are the same. We have not yet mentioned units for measuring angles. If we piek a unit to agree with the are length, we would have exact agreement: The cosine of an angle of [math]u[/math] such units is equal to the cosine of the real number [math]u[/math] and the sine of an angle of [math]u[/math] sueh units is equal to the sine of the real number [math]u[/math]. This unit is ealled the radian and it should be obvious that there are [math]2\pi[/math] radians in an angle of one revolution. Another unit, probably more familiar to the reader, is the degree, which is [math]\frac{1}{360}[/math] of a revolution and [math]\frac{\pi}{180}[/math] of a radian. Thus the cosine of an angle of [math]d[/math] degrees is equal to the cosine of the real number [math]\frac{\pi d}{180}[/math].

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.