guide:08d5919107: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="d-none"><math> | |||

\newcommand{\ex}[1]{\item } | |||

\newcommand{\sx}{\item} | |||

\newcommand{\x}{\sx} | |||

\newcommand{\sxlab}[1]{} | |||

\newcommand{\xlab}{\sxlab} | |||

\newcommand{\prov}[1] {\quad #1} | |||

\newcommand{\provx}[1] {\quad \mbox{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\intext}[1]{\quad \mbox{#1} \quad} | |||

\newcommand{\R}{\mathrm{\bf R}} | |||

\newcommand{\Q}{\mathrm{\bf Q}} | |||

\newcommand{\Z}{\mathrm{\bf Z}} | |||

\newcommand{\C}{\mathrm{\bf C}} | |||

\newcommand{\dt}{\textbf} | |||

\newcommand{\goesto}{\rightarrow} | |||

\newcommand{\ddxof}[1]{\frac{d #1}{d x}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddx}{\frac{d}{dx}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddt}{\frac{d}{dt}} | |||

\newcommand{\dydx}{\ddxof y} | |||

\newcommand{\nxder}[3]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{d{#3}^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\deriv}[2]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{dx^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\dist}{\mathrm{distance}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccot}{\mathrm{arccot\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccsc}{\mathrm{arccsc\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsec}{\mathrm{arcsec\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arctanh}{\mathrm{arctanh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsinh}{\mathrm{arcsinh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccosh}{\mathrm{arccosh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\sech}{\mathrm{sech\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\csch}{\mathrm{csch\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\conj}[1]{\overline{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb} | |||

</math></div> | |||

Special among infinite series which contain both positive and negative terms are those whose terms alternate in sign. More precisely, we define the series <math>\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i</math> to be \textbf{alternating} if <math>a_{i}a_{i+1} < 0</math> for every integer <math>i \geq m</math>. It follows from this definition that an alternating series is one which can be written in one of the two forms | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\sum_{i=1}^\infty (-1)^{i}b_{i}\;\;\; \mbox{or} \;\;\; \sum_{i=m}^\infty (-1)^{i+1}b_{i}, | |||

</math> | |||

where <math>b_i > 0</math> for every integer <math>i \geq m</math>. An example is the '''alternating harmonic series''' | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\sum_{i=1}^\infty (-1)^{i+1} = 1 - \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} - \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{5} - \cdots . | |||

</math> | |||

An alternating series converges under surprisingly weak conditions. The next theorem gives two simple hypotheses whose conjunction is sufficient to imply convergence. | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-1|The alternuting series <math>\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i</math> concerges if: | |||

<ul style{{=}}"list-style-type:lower-roman"> | |||

<li> <math>|a_{n + 1}| \leq |a_n|, \;\;\; \mathrm{for every integer} n \geq m, \;\mathrm{and}</math> </li> | |||

<li><math>\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} a_n = 0 \;\mathrm{(or, equivalently,} \; \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} |a_n| = 0).</math></li> | |||

</ul> | |||

|We shall assume for convenience and with no loss of generality that <math>m = 0</math> and that <math>a_i = (-1)^{i} b_i</math>, with <math>b_i > 0</math> for every integer <math>i \geq 0</math>. The series is therefore <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty (-1)^{i} b_i</math>, and the hypotheses (i) and (ii) become | |||

<ul style{{=}}"list-style-type:lower-roman"> | |||

<li><math>b_{n + 1} \leq b_n, \;\;\; \mbox{for every integer $n \geq 0$, and}</math> </li> | |||

<li><math>\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} b_n = 0.</math></li> | |||

</ul> | |||

The proof is completed by showing the convergence of the sequence <math>\{s_n \}</math> of partial sums, which is defined recursively by the equations | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

s_0 &=& (-1)^0 b_0= b_0,\\ | |||

s_n &=& s_{n-1} + ( - 1 )^n b_n, \;\;\; n = 1, 2, 3, .... | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

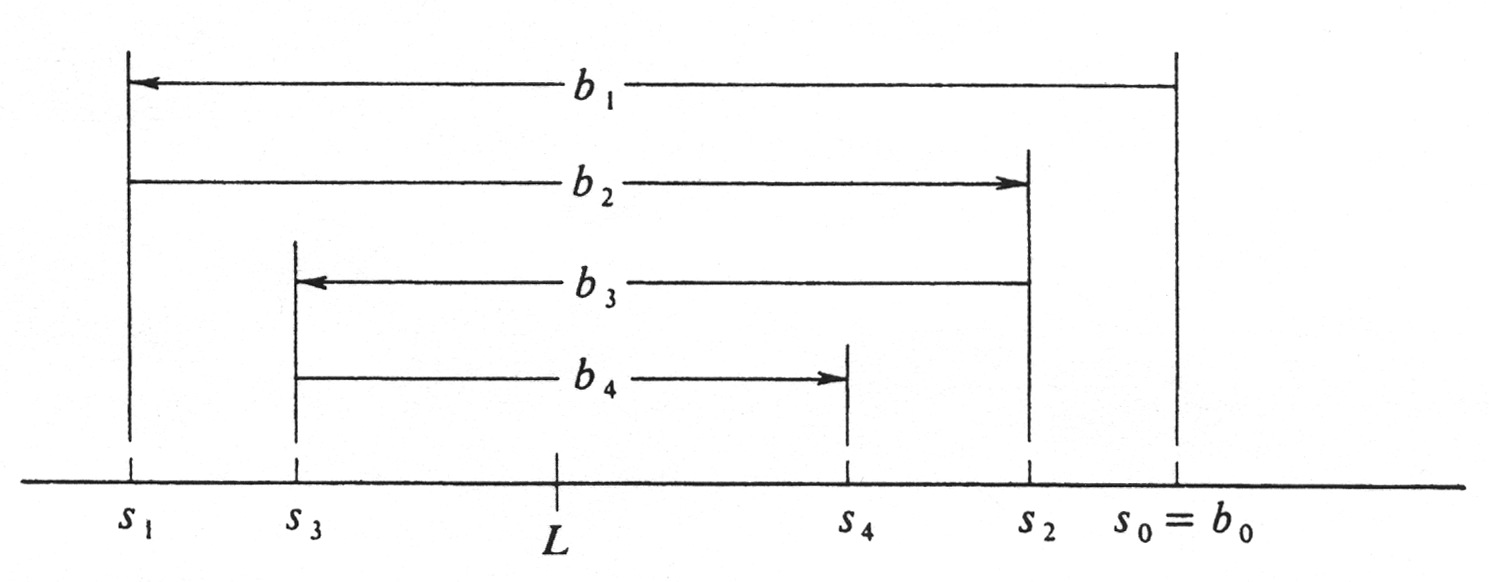

The best proof that <math>\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_n</math>, exists is obtained by an illustration. In Figure 5 we first plot the point <math>s_0 = b_0</math> and then the point <math>s_1 = s_0 - b_1</math>. Next we | |||

plot <math>s_2 = s_1 + b_2</math> and observe that, since <math>b_2 \leq b_1</math>, we have <math>s_2 \leq s_0</math>. After that comes <math>s_3 = s_2 - b_3</math> and, since <math>b_3 \leq b_2</math> it follows that <math>s_1 \leq s_3</math>. Continuing in this way, we see that the odd-numbered points of the sequence <math>\{s_n\}</math> form an increasing subsequence: | |||

<div id{{=}}"fig 9.5" class{{=}}"d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig9_5.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq9.4.1"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

s_1 \leq s_3 \leq s_5 \leq \cdots \leq s_{2n-1} \leq \cdots, | |||

\label{eq9.4.1} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

and the even-numbered points form a decreasing subsequence: | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

s_0 \geq s_2 \geq s_4 \geq \cdots \geq s_{2n} \geq \cdots. | |||

</math> | |||

Furthermore, every odd-numbered partial sum is less than or equal to every even-numbered one. Thus the increasing sequence (1) is bounded above by any one of the numbers <math>s_{2n}</math>, and it therefore converges [see (1.4), page 479]. That is, there exists a real number <math>L</math> such that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_{2n - 1} = L. | |||

</math> | |||

For every integer <math>n \geq 1</math>, we have | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

s_{2n} = s_{2n - 1} + b_{2n}, | |||

</math> | |||

and, since it follows from (ii') that <math>\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} b_{2n} = 0</math>, we conclude that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_{2n} &=& \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_{2n - 1} + \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_{2n} \\ | |||

&=& L - 0 = L. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

We have shown that both the odd-numbered subsequences <math>\{s_{2n-1} \}</math> and the even-numbered subsequence <math>\{ s_{2n} \}</math> converge to the same limit <math>L</math>. This implies that <math>\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_n = L</math>. For, given an arbitrary real number <math> \epsilon > 0</math>, we have proved that there exist integers <math>N_1</math>, and <math>N_2</math>, such that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

|s_{2n-1} - L| & < & \epsilon, \;\;\;\mbox{whenever}\; 2n - 1 > N_1, \\ | |||

|s_{2n} -L| & < & \epsilon, \;\;\;\mbox{whenever}\; 2n > N_2. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

Hence, if <math>n</math> is any integer (odd or even) which is greater than both <math>N_1</math> and <math>N_2</math>, then <math>|s_n - L| < \epsilon</math>. Thus | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

L = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_n = \sum_{i=0}^\infty (-1)^{i} b_i, | |||

</math> | |||

and the proof is complete.}} | |||

As an application of Theorem (4.1) consider the alternating harmonic series | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\sum_{ i=1}^\infty (-1)^{i + 1} \frac{1}{i} = 1 - \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} - \frac{1}{4} + \cdots . | |||

</math> | |||

The hypotheses of the theorem are obviously satisfied: | |||

<ul style="list-style-type:lower-roman"> | |||

<li><math>\frac{1}{n + 1} \leq \frac{1}{n}, \;\;\; \mbox{for every integer $n \geq 1$, and}</math></li> | |||

<li><math>\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} (-1)^{n+1} \frac{1}{n} = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{n} = 0.</math></li> | |||

</ul> | |||

Hence it follows that the alternating harmonic series is convergent. It is interesting to compare this series with the ordinary harmonic series | |||

<math> \sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{i} = 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} +\frac{1}{4} + \cdots </math>, which we have shown to be divergent. We see that the alternating harmonic series is a convergent infinite series <math>\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} a_i</math> for which the corresponding series of absolute values <math>\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} |a_i|</math> fail diverges. | |||

For practical purposes, the value of a convergent infinite series <math>\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} a_i</math> is usually approximated by a partial <math>\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} a_i</math>. The '''error''' in the approximation, denoted by <math>E_n</math>, is the absolute value of the difference between the true value of the series and the approximating partial sum; i.e., | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

E_n = | \sum_{i=m}^{\infty} a_i - \sum_{i=m}^{n} a_i | . | |||

</math> | |||

ln general, it is a difficult problem to know how large <math>n</math> must be chosen to cosure that the error <math>E_n</math> be less than a given size. However, for those alternating series which satisfy the hypotheses of Theorem (4.1), the problem is an easy one. | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-2|If the ulternating series <math>\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} a_i</math> satisfies hypotheses (i) and (ii) of Theorem (4.1), then the error <math>E_n</math> is less than or equal to the absolute value of the first omitted term. That is, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

E_n \leq |a_{n+1}|, \;\;\; \mbox{for every integer} \; n \geq m. | |||

</math> | |||

|We shall use the same notation as in the proof of (4.1). Thus we assume that <math> m = 0</math> and that <math>a_i = (-1)^{i} b_i</math> where <math>b_i > 0</math> for every integer <math>i \geq 0</math>. The value of the series is the number <math>L</math>, and the error <math>E_n</math> is therefore given by | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

E_n = | \sum_{i=0}^{\infty} a_i - \sum_{i=0}^{n} a_i | = |L - s_n| . | |||

</math> | |||

Since <math>|a_{n+1}| = b_{n+1}</math>, the proof is completed by showing that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

|L - s_n| \leq b_{n+1}, \; \mbox{for every integer}\; n \geq 0. | |||

</math> | |||

Geometrically, <math>|L - s_n|</math> is the distance between the points <math>L</math> and <math>s_n</math> and it can be seen immediately from Figure 5 that the preceding inequality is true. To arrive at the conclusion formally, we recall that <math>\{s_{2n-1} \}</math> is an increasing sequence converging to <math>L</math>, and that <math>\{s_{2n} \}</math> is a decreasing sequence converging to <math>L</math>. Thus if <math>n</math> is odd, then <math>n + 1</math> is even and | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

s_n \leq L \leq s_{n+1}. | |||

</math> | |||

On the other hand, if <math>n</math> is even, then <math>n + 1</math> is odd and | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

s_{n +1} \leq L \leq s_n. | |||

</math> | |||

In either case, we have <math>|L - s_n| \leq |s_{n+1} - s_n|</math>. Hence, for every integer <math>n \geq 0</math>, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

E_n = |L - s_n| \leq |s_{n+1} - s_n| = |a_{n+1}|, | |||

</math> | |||

and the proof is complete.}} | |||

==General references== | |||

{{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | |||

Latest revision as of 02:35, 20 November 2024

Special among infinite series which contain both positive and negative terms are those whose terms alternate in sign. More precisely, we define the series [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i[/math] to be \textbf{alternating} if [math]a_{i}a_{i+1} \lt 0[/math] for every integer [math]i \geq m[/math]. It follows from this definition that an alternating series is one which can be written in one of the two forms

where [math]b_i \gt 0[/math] for every integer [math]i \geq m[/math]. An example is the alternating harmonic series

An alternating series converges under surprisingly weak conditions. The next theorem gives two simple hypotheses whose conjunction is sufficient to imply convergence.

The alternuting series [math]\sum_{i=m}^\infty a_i[/math] concerges if:

- [math]|a_{n + 1}| \leq |a_n|, \;\;\; \mathrm{for every integer} n \geq m, \;\mathrm{and}[/math]

- [math]\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} a_n = 0 \;\mathrm{(or, equivalently,} \; \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} |a_n| = 0).[/math]

We shall assume for convenience and with no loss of generality that [math]m = 0[/math] and that [math]a_i = (-1)^{i} b_i[/math], with [math]b_i \gt 0[/math] for every integer [math]i \geq 0[/math]. The series is therefore [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty (-1)^{i} b_i[/math], and the hypotheses (i) and (ii) become

- [math]b_{n + 1} \leq b_n, \;\;\; \mbox{for every integer $n \geq 0$, and}[/math]

- [math]\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} b_n = 0.[/math]

The proof is completed by showing the convergence of the sequence [math]\{s_n \}[/math] of partial sums, which is defined recursively by the equations

The best proof that [math]\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_n[/math], exists is obtained by an illustration. In Figure 5 we first plot the point [math]s_0 = b_0[/math] and then the point [math]s_1 = s_0 - b_1[/math]. Next we

plot [math]s_2 = s_1 + b_2[/math] and observe that, since [math]b_2 \leq b_1[/math], we have [math]s_2 \leq s_0[/math]. After that comes [math]s_3 = s_2 - b_3[/math] and, since [math]b_3 \leq b_2[/math] it follows that [math]s_1 \leq s_3[/math]. Continuing in this way, we see that the odd-numbered points of the sequence [math]\{s_n\}[/math] form an increasing subsequence:

We have shown that both the odd-numbered subsequences [math]\{s_{2n-1} \}[/math] and the even-numbered subsequence [math]\{ s_{2n} \}[/math] converge to the same limit [math]L[/math]. This implies that [math]\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} s_n = L[/math]. For, given an arbitrary real number [math] \epsilon \gt 0[/math], we have proved that there exist integers [math]N_1[/math], and [math]N_2[/math], such that

As an application of Theorem (4.1) consider the alternating harmonic series

The hypotheses of the theorem are obviously satisfied:

- [math]\frac{1}{n + 1} \leq \frac{1}{n}, \;\;\; \mbox{for every integer $n \geq 1$, and}[/math]

- [math]\lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} (-1)^{n+1} \frac{1}{n} = \lim_{n \rightarrow \infty} \frac{1}{n} = 0.[/math]

Hence it follows that the alternating harmonic series is convergent. It is interesting to compare this series with the ordinary harmonic series [math] \sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{1}{i} = 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} +\frac{1}{4} + \cdots [/math], which we have shown to be divergent. We see that the alternating harmonic series is a convergent infinite series [math]\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} a_i[/math] for which the corresponding series of absolute values [math]\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} |a_i|[/math] fail diverges. For practical purposes, the value of a convergent infinite series [math]\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} a_i[/math] is usually approximated by a partial [math]\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} a_i[/math]. The error in the approximation, denoted by [math]E_n[/math], is the absolute value of the difference between the true value of the series and the approximating partial sum; i.e.,

ln general, it is a difficult problem to know how large [math]n[/math] must be chosen to cosure that the error [math]E_n[/math] be less than a given size. However, for those alternating series which satisfy the hypotheses of Theorem (4.1), the problem is an easy one.

If the ulternating series [math]\sum_{i=m}^{\infty} a_i[/math] satisfies hypotheses (i) and (ii) of Theorem (4.1), then the error [math]E_n[/math] is less than or equal to the absolute value of the first omitted term. That is,

We shall use the same notation as in the proof of (4.1). Thus we assume that [math] m = 0[/math] and that [math]a_i = (-1)^{i} b_i[/math] where [math]b_i \gt 0[/math] for every integer [math]i \geq 0[/math]. The value of the series is the number [math]L[/math], and the error [math]E_n[/math] is therefore given by

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.