guide:550877833d: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="d-none"><math> | |||

\newcommand{\ex}[1]{\item } | |||

\newcommand{\sx}{\item} | |||

\newcommand{\x}{\sx} | |||

\newcommand{\sxlab}[1]{} | |||

\newcommand{\xlab}{\sxlab} | |||

\newcommand{\prov}[1] {\quad #1} | |||

\newcommand{\provx}[1] {\quad \mbox{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\intext}[1]{\quad \mbox{#1} \quad} | |||

\newcommand{\R}{\mathrm{\bf R}} | |||

\newcommand{\Q}{\mathrm{\bf Q}} | |||

\newcommand{\Z}{\mathrm{\bf Z}} | |||

\newcommand{\C}{\mathrm{\bf C}} | |||

\newcommand{\dt}{\textbf} | |||

\newcommand{\goesto}{\rightarrow} | |||

\newcommand{\ddxof}[1]{\frac{d #1}{d x}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddx}{\frac{d}{dx}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddt}{\frac{d}{dt}} | |||

\newcommand{\dydx}{\ddxof y} | |||

\newcommand{\nxder}[3]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{d{#3}^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\deriv}[2]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{dx^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\dist}{\mathrm{distance}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccot}{\mathrm{arccot\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccsc}{\mathrm{arccsc\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsec}{\mathrm{arcsec\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arctanh}{\mathrm{arctanh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsinh}{\mathrm{arcsinh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccosh}{\mathrm{arccosh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\sech}{\mathrm{sech\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\csch}{\mathrm{csch\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\conj}[1]{\overline{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb} | |||

</math></div> | |||

For every power series | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_i(x - a)^i, | |||

</math> | |||

the '''function defined by the power series''' is the function <math>f</math> which, to every real number <math>c</math> at which the power series converges, assigns the real number <math>f(c)</math> given by | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f(c) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_i(c - a)^i. | |||

</math> | |||

The domain of <math>f</math> is obviously equal to the interval of convergence of the power series. Speaking more casually, we say simply that the function <math>f</math> is defined by the equation | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f(x) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_i(x - a)^i. | |||

</math> | |||

As an example, let <math>f</math> be the function defined by | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f(x) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty \frac{x^i}{ i!} = 1 + x + \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^3}{3!} + \cdots . | |||

</math> | |||

This power series was studied in Example 1 of Section 6 and was shown to converge for all values of <math>x</math>. Thus the domain of the function which the series defines is the set of all real numbers. | |||

Functions defined by power series have excellent analytic properties. One of the most important is the fact that every such function is differentiable and that its derivative is the function defined by the power series obtained by differentiating the original series term by term. That | |||

is, if | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f(x) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x-a)^i = a_0 + a_{1}(x-a) + a_{2}(x-a)^2 + \cdots , | |||

</math> | |||

then | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f'(x) = \sum_{i=1}^\infty i a_{i} (x-a)^{i-1} = a_{1} + 2a_{2}(x-a) + 3a_{3}(x-a)^2 + \cdots . | |||

</math> | |||

This is not a trivial result. To prove it, we begin with the following theorem: | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-1|A power series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x-a)^i</math> and its derived series <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty ia_{i} (x-a)^{i-1}</math> have the same radius of convergence. | |||

In Section 6 we showed that the essential difference between the power series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x-a)^i</math> and the corresponding series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}x^i</math> is that the interval of convergence of one is obtained from that of the other by translation. In particular, both series have the same radius of convergence. To prove (7.1), it is therefore sufficient (and rotationally easier) to prove the same result for power series about the origin 0. We shall therefore prove the following: If the power series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}x^i</math> has radius of convergence <math>\rho</math> and if the derived series <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty ia_{i}x^{i-1}</math> has radius of convergence <math>\rho'</math>, then <math>\rho = \rho'</math>. | |||

|Suppose that <math>\rho < \rho'</math>, and let <math>c</math> be an arbitrary real number such that <math>\rho < c < \rho'</math>. Then the series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}c^i</math> diverges, whereas the series <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty i a_{i}c^{i-1}</math> converges absolutely. Since <math>c</math> is positive, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

c \sum_{i=1}^\infty |ia_{i}c^{i-1}| = \sum_{i=1}^\infty |ia_{i}c^i|, | |||

</math> | |||

and it follows that the series <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty = ia_{i}c^i</math> is also absolutely convergent. However, it is obvious that, for every positive integer <math>i</math>, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

|a_{i}c^i| \leq i |a_{i}c^i| = |ia_{i}c^i|. | |||

</math> | |||

The Comparison Test therefore implies that the series <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty |a_{i}c^i|</math> converges, and this fact implies the convergence of <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}c^i</math>, which is a contradiction. Hence the original assumption is false, and we conclude that | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq9.7.1"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

\rho' \leq \rho. | |||

\label{eq9.7.1} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

Next, suppose that <math>\rho' < \rho</math>. We shall derive a contradiction from this assumption also, which, together with the inequality (1), proves that <math>\rho' = \rho</math>. Let <math>b</math> and <math>c</math> be any two real numbers such that <math>\rho' < b < c < \rho</math>. It follows | |||

from the definition of <math>\rho'</math> that the series <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty ia_{i}b^{i-1}</math> diverges. Similarly, from the definition of <math>\rho</math>, we know that the series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}c^i</math> converges, and therefore <math>\lim_{i \rightarrow \infty} a_ic^i = 0</math>. Because <math>c</math> is positive, it follows that there exists a positive integer <math>N</math> such that, for every integer <math>i \geq N</math>, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

|a_{i}c^i| < c. | |||

</math> | |||

But <math>|a_ic^i| = |a_i|c^i</math>, and so the preceding inequality becomes <math>|a_i|c^i < c</math>, or, equivalently, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

|a_i| < \frac{1}{c^{i-1}}. | |||

</math> | |||

Hence, since <math>b</math> is also positive, we obtain | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

|ia_{i}b^{i-1}| = ib^{i-1} |a_i| < i \frac{b^{i-1}}{c^{i-1}} = i\Bigl(\frac{b}{c}\Bigr)^{i-1} , | |||

</math> | |||

for every integer <math>i \geq N</math>. Let us set <math>\frac{b}{c} = r</math>. Then <math>0 < r < 1</math>, and we have shown that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

|ia_{i}b^{i-1}| < ir^{i-1}, \;\;\;\mbox{for every integer}\; i \geq N . | |||

</math> | |||

However, it is shown in Example 3, page 508, that the series <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty ir^{i-1}</math> converges if <math>|r| < 1</math>. Hence the preceding inequality and the Comparison Text imply that the series <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty |ia_{i}b^{i-1}|</math> converges, and this contradicts the above conclusion that <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty ia_{i}b^{i-1}</math> diverges. This completes the proof that <math>\rho' = \rho</math>, and, as we have remarked, also proves (7.1).}} | |||

Note that Theorem (7.1) does not state that a power series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x-a)^i</math> and its derived series have the same ''intertval'' of convergence, but only that they have the same ''radius'' of convergence. For example, in Example 1(b), page 514, the interval of convergence of the power series <math>\sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1)^{k-1} \frac{x^k}{k}</math> is shown to be the half-open interval <math>(-1,1]</math>. However, the derived series is | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1)^{k-1} k \frac{x^{k-1}}{k} | |||

&=& \sum_{k=1}^\infty ( -1)^{k-1} x^{k-1} \\ | |||

&=& 1 - x + x^2 - x^3 + \cdots , | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

which does not converge for <math>x = 1</math>. It is a geometric series having the open interval of convergence <math>(-1, 1)</math>. | |||

Let <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x-a)^i</math> be a power series, and let <math>f</math> and <math>g</math> be the two functions defined respectively by <math>f(x) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x-a)^i</math> and by <math>g(x) = \sum_{i=1}^\infty ia_{i}(x -a)^{i-1}</math>. We have proved that there is an interval, which, with the | |||

possible exception of its endpoints, is the common domain of <math>f</math> and <math>g</math>. However, we have not yet proved that the function <math>g</math> is the derivative of the function <math>f</math>. This fact is the content of the following theorem. | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-2|THEOREM. If the radius of convergence <math>\rho</math> of the power series <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_i (x-a)^i</math> is not zero, then the function <math>f</math> defined by <math>f(x) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_i(x-a)^i</math> is differentiable at ecery <math>x</math> such that <math>|x-a| < \rho</math> and | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f'(x) = \sum_{i=1}^\infty ia_i(x-a)^{i-1}. | |||

</math> | |||

|It is a direct consequence of the Chain Rule that if (7.2) is proved for <math>a = 0</math>, then it is true in general. We shall therefore assume that <math>f(x) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_ix^i</math>. Let <math>g</math> be the function defined by <math>g(x) = \sum_{i=1}^\infty i a_i x^{i-1}</math>, and let <math>c</math> be an arbitrary number such that <math>|c| < \rho</math>. We must prove that <math>f'(c)</math>, which can be defined by | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f'(c) = \lim_{x \rightarrow c} \frac{f(x)- f(c)}{x - c} , | |||

</math> | |||

exists and is equal to <math>g(c)</math>. Hence the proof is complete when we show that | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq9.7.2"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

\lim_{x \rightarrow c} \Bigl(\frac{f(x) - f(c)}{x-c} - g(c)\Bigr) = 0. | |||

\label{eq9.7.2} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

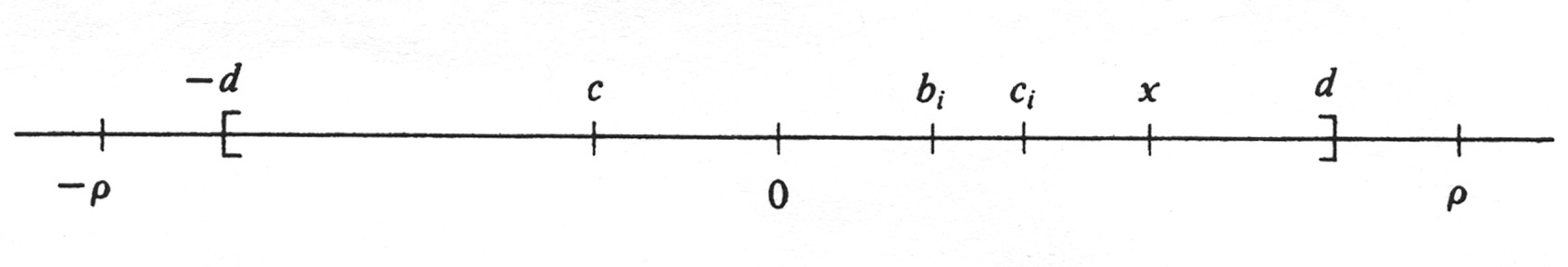

Let <math>d</math> be an arbitrary real number such that <math>|c| < d < \rho</math> (see Figure 9). | |||

<div id{{=}}"fig 9.9" class{{=}}"d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig9_9.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

Henceforth, we shall consider only values of <math>x</math> which lie in the closed interval <math>[-d, d]</math>. For every such <math>x</math> other than <math>c</math>, we have | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\frac{f(x) - f(c)}{x-c} | |||

&=& \frac{1}{x - c} \Bigl(\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_i x^i - \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_i c^i\Bigr)\\ | |||

&=& \sum_{i=1}^\infty a_i \Bigl(\frac{x^i - c^i}{x-c} \Bigl). | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

For each integer <math>i \geq 1</math>, we apply the Mean Value Theorem to the function <math>x^i</math>, whose derivative is <math>ix^{i-1}</math>. The conclusion is that, for each <math>i</math>, there exists a real number <math>c_i</math> in the open interval whose endpoints are <math>c</math> and <math>x</math> such that <math>x^i - c^i = ic_{i}^{i-1}(x-c)</math>. Hence | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\frac{x^i - c^i}{x-c} = ic_i^{i-1} , | |||

</math> | |||

and so | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\frac{f(x) - f(c)}{x - c} = \sum_{i=1}^\infty ia_i c_i^{i-1} . | |||

</math> | |||

From this it follows that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

\frac{f(x) - f(c)}{x - c} - g(c) | |||

&=& \sum_{i=1}^\infty ia_ic_i^{i -1} - \sum_{i=1}^\infty ia_i c^{i -1} \\ | |||

&=& \sum_{i=2}^\infty ia_i(c_i^{i -1} - c^{i-1}). | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

noindent For each integer <math>i \geq 2</math>, we now apply the Mean Value Theorem to the function <math>x^{i-1}</math>, whose derivative is <math>(i-1)x^{i-2}</math>. We conclude that there exists a real number <math>b_i</math> in the open interval whose endpoints are <math>c</math> and <math>c_i</math> such that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

c_i^{i-1} - c^{i-1} = (i- 1)b_i^{i-2}(c_i - c). | |||

</math> | |||

Hence | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\frac{f(x) - f(c)}{x-c} - g(c) = \sum_{i=2}^\infty i(i-1 )a_i b_i^{i-2} (c_i - c). | |||

</math> | |||

Since <math>|c_i-c| \leq |x-c|</math>, for every <math>i</math>, we obtain, using Theorem (5.3), page 509, | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq9.7.3"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

\Big|\frac{f(x) - f(c)}{x-c} - g(c)\Big| \leq |x - c| \sum_{i=2}^\infty |i(i-1)a_ib_i^{i-2} | . | |||

\label{eq9.7.3} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

Two applications of (7.1) imply that the power series <math>\sum_{i=2}^\infty i(i-1) a_i x^{i-2}</math>, which is the derived series of <math>\sum_{i=1}^\infty i a_ix^{i-1}</math>, also has radius of convergence equal to <math>\rho</math>, and it is therefore absolutely convergent for <math>x = d</math>. Moreover, <math>|b_i| < d</math> for each <math>i</math>, and so | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

|i(i- 1)a_i b_i^{i -2}| \leq | i(i-1)a_id^{i -2}|, | |||

</math> | |||

for every integer <math>i \geq 2</math>. It follows from the Comparison Test that | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq9.7.4"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

\sum_{i=2}^\infty |i(i- 1)a_ib_i^{i-2}| \leq \sum_{i=2}^\infty |i(i- 1)a_id^{i -2}. | |||

\label{eq9.7.4} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

The value of the series on the right in (4) does not depend on <math>x</math>, and we denote it by <math>M</math>. Combining (3) and (4), we therefore finally obtain | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\Big|\frac{f(x)- f(c)}{x-c} - g(c)\Big| \leq |x - c| M. | |||

</math> | |||

The left side of this inequality can be made arbitrarily small by taking <math>|x-c|</math> sufficiently small. But this is precisely the meaning of the assertion in (2), and so the proof is finished.}} | |||

'''Example''' | |||

(a) Show that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

e^x = \sum_{i=0}^\infty \frac{x^i}{i!} = 1 + x + \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^3}{3!} + \cdots . | |||

</math> | |||

for every real number <math>x</math>, and (b) show that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\ln(1 + x) = \sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1)^{k-1} \frac{x^k}{k} = x - \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^3}{3!} - \cdots . | |||

</math> | |||

for every real number <math>x</math> such that <math>|x| < 1</math>. | |||

For (a), let <math>f</math> be the function defined by <math>f(x) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty \frac{x^i}{i!}</math>. We have already shown that the domain of <math>f</math> is the set of all real numbers; i.e., the radius of convergence is infinite. It follows from the preceding theorem that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f'(x) = \sum_{i=1}^\infty i \frac{x^{i-1}}{i!} , \;\;\;\mbox{for every real number}\; x. | |||

</math> | |||

Since <math>\frac{i}{i!} = \frac{1}{(i- 1)!}</math>, we obtain | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{ix^{i-1}}{i!} = \sum_{i=1}^\infty \frac{x^{i-1}}{(i-1)!} = \sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{x^k}{k!}, | |||

</math> | |||

where the last equation is obtained by replacing <math>i - 1</math> by <math>k</math>. Thus we have proved that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f'(x) = f(x)\;\;\;\mbox{for every real number}\; x. | |||

</math> | |||

The function <math>f</math> therefore satisfies the differential equation <math>\frac{dy}{dx} = y</math>, whose general solution is <math>y = ce^x</math>. Hence <math>f(x) = ce^x</math> for some constant <math>c</math>. But it is obvious from the series which defines <math>f</math> that <math>f(0) = 1</math>. It follows that <math>c = 1</math>, and (a) is proved. | |||

A similar technique is used for (b). Let <math>f(x) = \sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1)^{k-1} \frac{x^k}{k}</math>. The domain of <math>f</math> is the half-open interval <math>(-1, 1]</math>, and the radius of convergence is 1. Hence | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

f'(x) &=& \sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1)^{k-1} \frac{k-1}{k} | |||

= \sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1 )^{k-1} x^{k-1}\\ | |||

&=& 1 - x + x^2 - x^3 + \cdots , | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

for <math>|x| < 1</math>. The latter is a geometric series with sum equal to <math>\frac{1}{1 + x}</math>. Hence we have shown that | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f'(x) = \frac{dx}{1+x}, \;\;\;\mbox{for every $x$ such that}\; |x| < 1. | |||

</math> | |||

Integration yields | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f(x) = \int \frac{dx}{1+x} = \ln |1 +x| + c. | |||

</math> | |||

Since <math>|x| < 1</math>, we have <math>|1 + x| = (1 + x)</math>. From the series which defines <math>f</math> we see that <math>f(0) = 0</math>. Hence | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

0 = f(0) = \ln(1 + 0) + c = 0 + c = c. | |||

</math> | |||

lt follows that <math>f(x) = \ln(1 + x)</math> for every real number <math>x</math> such that <math>|x| < 1</math>, and (b) is therefore established. | |||

Example 1 illustrates an important point. The domain of the function <math>f</math> defined by <math>f(x) = \sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1)^{k-1} \frac{x^k}{k} </math> is the half-open interval <math>(-1, 1]</math>. On the other hand, the domain of the function <math>\ln(1 + x)</math> is the unbounded interval <math>(-1, \infty)</math>. It is essential to realize that the equation | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\ln (1 + x) = \sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1)^{k-1} \frac{x^k}{k} | |||

</math> | |||

has been shown to hold ''only for values of <math>x</math> which are interior points of the interval of convergence of the power series.'' It certainly does not hold at points outside the interval of convergence where the series diverges. As far as the endpoints of the interval are concerned, it can be proved that a function defined by a power series is continuous at every point of its interval of convergence. Hence the above equation does in fact hold for <math>x = 1</math>, and we therefore obtain the following formula for the sum of the alternating harmonic series: | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\ln 2 = \sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1)^{k-1} \frac{1}{k} = 1 - \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} - \frac{1}{4} + \cdots . | |||

</math> | |||

Let <math>\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x - a)^i</math> be a power series with a nonzero radius of convergence <math>\rho</math>, and let <math>f</math> be the function defined by the power series | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f(x) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x - a)^i, | |||

</math> | |||

for every <math>x</math> in the interval of convergence. By iterated applications of Theorem (7.2), i.e., first to the series, then to the derived series, then to the derived series of the derived series, etc., we may conclude that <math>f</math> has derivatives of arbitrarily high order within the radius of convergence. The formula for the nth derivative is easily seen to be | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-3| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f^{(n)}(x) = \sum_{i=n}^\infty i(i - 1) \cdots (i - n + 1)a_i(x - a)^{i-n} , | |||

</math> | |||

for every <math>x</math> such that <math>|x - a| < \rho</math>.|}} | |||

Is it possible for a function <math>f</math> to be defined by two different power series about the same number <math>a</math>? The answer is no, provided the domain of <math>f</math> is not just the single number <math>a</math>. The reason, as the following corollary of Theorem (7.3) shows, is that the coefficients of any power series about <math>a</math> which defines <math>f</math> are uniquely determined by the function <math>f</math>. | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-4|lf <math>f(x) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_i(x-a)^i</math> and if the radius of convergence of the power series is not zero, then, for every integer <math>n \geq 0</math>, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

a_n = \frac{1}{n!} f^{(n)}(a). | |||

</math> | |||

[By the zeroth derivative <math>f^{(0)}</math> we mean simply <math>f</math> itself. Hence, for <math>n = 0</math>, the conclusion is the obviously true equation <math>a_0 = f(a)</math>.] | |||

|The radius of convergence <math>\rho</math> is not zero, and so the formula in (7.3) holds. Since <math>i(i-1) \cdots (i - n + 1) = \frac{i!}{(i-n)!}</math>, we obtain | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

f^{(n)}(x) &=& \sum_{i=n}^\infty \frac{i!}{(i - n)!} a_i (x - a)^{i-n} \\ | |||

&=& n! a_n + (n + 1)! a_{n+1}(x - a) + \frac{(n+2)!}{2!} a_{n+2}(x - a)^2 + \cdots , | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

for every <math>x</math> such that <math>|x-a| < \rho</math>. Setting <math>x = a</math>, we obtain | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

f^{(n)}(a)= n!a_n, | |||

</math> | |||

from which the desired conclusion follows.}} | |||

==General references== | |||

{{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | |||

Latest revision as of 00:03, 21 November 2024

For every power series

the function defined by the power series is the function [math]f[/math] which, to every real number [math]c[/math] at which the power series converges, assigns the real number [math]f(c)[/math] given by

The domain of [math]f[/math] is obviously equal to the interval of convergence of the power series. Speaking more casually, we say simply that the function [math]f[/math] is defined by the equation

As an example, let [math]f[/math] be the function defined by

This power series was studied in Example 1 of Section 6 and was shown to converge for all values of [math]x[/math]. Thus the domain of the function which the series defines is the set of all real numbers. Functions defined by power series have excellent analytic properties. One of the most important is the fact that every such function is differentiable and that its derivative is the function defined by the power series obtained by differentiating the original series term by term. That is, if

then

This is not a trivial result. To prove it, we begin with the following theorem:

A power series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x-a)^i[/math] and its derived series [math]\sum_{i=1}^\infty ia_{i} (x-a)^{i-1}[/math] have the same radius of convergence. In Section 6 we showed that the essential difference between the power series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x-a)^i[/math] and the corresponding series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}x^i[/math] is that the interval of convergence of one is obtained from that of the other by translation. In particular, both series have the same radius of convergence. To prove (7.1), it is therefore sufficient (and rotationally easier) to prove the same result for power series about the origin 0. We shall therefore prove the following: If the power series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}x^i[/math] has radius of convergence [math]\rho[/math] and if the derived series [math]\sum_{i=1}^\infty ia_{i}x^{i-1}[/math] has radius of convergence [math]\rho'[/math], then [math]\rho = \rho'[/math].

Suppose that [math]\rho \lt \rho'[/math], and let [math]c[/math] be an arbitrary real number such that [math]\rho \lt c \lt \rho'[/math]. Then the series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}c^i[/math] diverges, whereas the series [math]\sum_{i=1}^\infty i a_{i}c^{i-1}[/math] converges absolutely. Since [math]c[/math] is positive,

Next, suppose that [math]\rho' \lt \rho[/math]. We shall derive a contradiction from this assumption also, which, together with the inequality (1), proves that [math]\rho' = \rho[/math]. Let [math]b[/math] and [math]c[/math] be any two real numbers such that [math]\rho' \lt b \lt c \lt \rho[/math]. It follows from the definition of [math]\rho'[/math] that the series [math]\sum_{i=1}^\infty ia_{i}b^{i-1}[/math] diverges. Similarly, from the definition of [math]\rho[/math], we know that the series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}c^i[/math] converges, and therefore [math]\lim_{i \rightarrow \infty} a_ic^i = 0[/math]. Because [math]c[/math] is positive, it follows that there exists a positive integer [math]N[/math] such that, for every integer [math]i \geq N[/math],

Note that Theorem (7.1) does not state that a power series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x-a)^i[/math] and its derived series have the same intertval of convergence, but only that they have the same radius of convergence. For example, in Example 1(b), page 514, the interval of convergence of the power series [math]\sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1)^{k-1} \frac{x^k}{k}[/math] is shown to be the half-open interval [math](-1,1][/math]. However, the derived series is

which does not converge for [math]x = 1[/math]. It is a geometric series having the open interval of convergence [math](-1, 1)[/math].

Let [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x-a)^i[/math] be a power series, and let [math]f[/math] and [math]g[/math] be the two functions defined respectively by [math]f(x) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x-a)^i[/math] and by [math]g(x) = \sum_{i=1}^\infty ia_{i}(x -a)^{i-1}[/math]. We have proved that there is an interval, which, with the

possible exception of its endpoints, is the common domain of [math]f[/math] and [math]g[/math]. However, we have not yet proved that the function [math]g[/math] is the derivative of the function [math]f[/math]. This fact is the content of the following theorem.

THEOREM. If the radius of convergence [math]\rho[/math] of the power series [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_i (x-a)^i[/math] is not zero, then the function [math]f[/math] defined by [math]f(x) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_i(x-a)^i[/math] is differentiable at ecery [math]x[/math] such that [math]|x-a| \lt \rho[/math] and

It is a direct consequence of the Chain Rule that if (7.2) is proved for [math]a = 0[/math], then it is true in general. We shall therefore assume that [math]f(x) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_ix^i[/math]. Let [math]g[/math] be the function defined by [math]g(x) = \sum_{i=1}^\infty i a_i x^{i-1}[/math], and let [math]c[/math] be an arbitrary number such that [math]|c| \lt \rho[/math]. We must prove that [math]f'(c)[/math], which can be defined by

Henceforth, we shall consider only values of [math]x[/math] which lie in the closed interval [math][-d, d][/math]. For every such [math]x[/math] other than [math]c[/math], we have

Example

(a) Show that

for every real number [math]x[/math], and (b) show that

for every real number [math]x[/math] such that [math]|x| \lt 1[/math]. For (a), let [math]f[/math] be the function defined by [math]f(x) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty \frac{x^i}{i!}[/math]. We have already shown that the domain of [math]f[/math] is the set of all real numbers; i.e., the radius of convergence is infinite. It follows from the preceding theorem that

Since [math]\frac{i}{i!} = \frac{1}{(i- 1)!}[/math], we obtain

where the last equation is obtained by replacing [math]i - 1[/math] by [math]k[/math]. Thus we have proved that

The function [math]f[/math] therefore satisfies the differential equation [math]\frac{dy}{dx} = y[/math], whose general solution is [math]y = ce^x[/math]. Hence [math]f(x) = ce^x[/math] for some constant [math]c[/math]. But it is obvious from the series which defines [math]f[/math] that [math]f(0) = 1[/math]. It follows that [math]c = 1[/math], and (a) is proved. A similar technique is used for (b). Let [math]f(x) = \sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1)^{k-1} \frac{x^k}{k}[/math]. The domain of [math]f[/math] is the half-open interval [math](-1, 1][/math], and the radius of convergence is 1. Hence

for [math]|x| \lt 1[/math]. The latter is a geometric series with sum equal to [math]\frac{1}{1 + x}[/math]. Hence we have shown that

Integration yields

Since [math]|x| \lt 1[/math], we have [math]|1 + x| = (1 + x)[/math]. From the series which defines [math]f[/math] we see that [math]f(0) = 0[/math]. Hence

lt follows that [math]f(x) = \ln(1 + x)[/math] for every real number [math]x[/math] such that [math]|x| \lt 1[/math], and (b) is therefore established.

Example 1 illustrates an important point. The domain of the function [math]f[/math] defined by [math]f(x) = \sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1)^{k-1} \frac{x^k}{k} [/math] is the half-open interval [math](-1, 1][/math]. On the other hand, the domain of the function [math]\ln(1 + x)[/math] is the unbounded interval [math](-1, \infty)[/math]. It is essential to realize that the equation

has been shown to hold only for values of [math]x[/math] which are interior points of the interval of convergence of the power series. It certainly does not hold at points outside the interval of convergence where the series diverges. As far as the endpoints of the interval are concerned, it can be proved that a function defined by a power series is continuous at every point of its interval of convergence. Hence the above equation does in fact hold for [math]x = 1[/math], and we therefore obtain the following formula for the sum of the alternating harmonic series:

Let [math]\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_{i}(x - a)^i[/math] be a power series with a nonzero radius of convergence [math]\rho[/math], and let [math]f[/math] be the function defined by the power series

for every [math]x[/math] in the interval of convergence. By iterated applications of Theorem (7.2), i.e., first to the series, then to the derived series, then to the derived series of the derived series, etc., we may conclude that [math]f[/math] has derivatives of arbitrarily high order within the radius of convergence. The formula for the nth derivative is easily seen to be

Is it possible for a function [math]f[/math] to be defined by two different power series about the same number [math]a[/math]? The answer is no, provided the domain of [math]f[/math] is not just the single number [math]a[/math]. The reason, as the following corollary of Theorem (7.3) shows, is that the coefficients of any power series about [math]a[/math] which defines [math]f[/math] are uniquely determined by the function [math]f[/math].

lf [math]f(x) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_i(x-a)^i[/math] and if the radius of convergence of the power series is not zero, then, for every integer [math]n \geq 0[/math],

The radius of convergence [math]\rho[/math] is not zero, and so the formula in (7.3) holds. Since [math]i(i-1) \cdots (i - n + 1) = \frac{i!}{(i-n)!}[/math], we obtain

for every [math]x[/math] such that [math]|x-a| \lt \rho[/math]. Setting [math]x = a[/math], we obtain

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.