guide:9760d838fd: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

</math></div> | </math></div> | ||

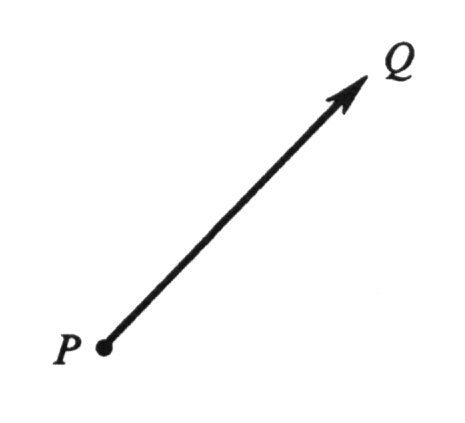

A '''vector''' in the plane is an ordered pair <math>(P, Q)</math> of points in the plane. The point <math>P</math> is called the '''initial point''' of the vector and <math>Q</math> the '''terminal point.''' Geometrically, the vector <math>(P, Q)</math> will be represented as a directed line segment, or arrow, from <math>P</math> to <math>Q</math>, as illustrated in Figure 10. We shall use boldface lower-case letters to denote vectors. For example, if <math>\mbox | A '''vector''' in the plane is an ordered pair <math>(P, Q)</math> of points in the plane. The point <math>P</math> is called the '''initial point''' of the vector and <math>Q</math> the '''terminal point.''' Geometrically, the vector <math>(P, Q)</math> will be represented as a directed line segment, or arrow, from <math>P</math> to <math>Q</math>, as illustrated in Figure 10. We shall use boldface lower-case letters to denote vectors. For example, if <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> is the vector with initial point <math>P</math> and terminal point <math>Q</math>, then <math>\mbox{\bf{v}} = (P, Q)</math>. | ||

= (P, Q)</math>. | |||

<div id="fig 10.10" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | <div id="fig 10.10" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | ||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig10_10.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | [[File:guide_c5467_scanfig10_10.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Having identified the plane with the set <math>R^2</math> of all ordered pairs of real numbers, we see that a vector is determined by four real numbers: two coordinates of its initial point, and two of its terminal point. Let <math>\mbox | |||

Having identified the plane with the set <math>R^2</math> of all ordered pairs of real numbers, we see that a vector is determined by four real numbers: two coordinates of its initial point, and two of its terminal point. Let <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> be a vector with initial point <math>P = (a, b)</math> and terminal point <math>Q = (c, d)</math>. Then the two numbers <math>v_1</math> and <math>v_2</math> given by the equations | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq10.3.1"/> | <span id{{=}}"eq10.3.1"/> | ||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

are defined to be '''first''' and '''second coordinates,''' respectively, of the vector <math>\mbox | are defined to be '''first''' and '''second coordinates,''' respectively, of the vector <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> in <math>R^2</math>. Thus we have defined coordinates of a vector in <math>R^2</math> as well as coordinates of a point in <math>R^2</math>. The definitions are not the same, although the concepts are certainly related. | ||

If a vector <math>\mbox | If a vector <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> has initial point <math>P = (a, b)</math> and coordinates <math>v_1</math> and <math>v_2</math>, then equations (1) tell us that the terminal point <math>Q = (c, d)</math> is given by | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

\begin{equation} | \begin{equation} | ||

\mbox | \mbox{\bf{v}} = (v_1, v_2)_P . | ||

\label{eq10.3.2} | \label{eq10.3.2} | ||

\end{equation} | \end{equation} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

[Although it would be consistent with this notation, we shall not write <math>(v_1, v_2)_{(a,b)}</math> for the vector with initial point <math>(a, b)</math> and coordinates <math>v_1</math> and <math>v_2</math>.] | [Although it would be consistent with this notation, we shall not write <math>(v_1, v_2)_{(a,b)}</math> for the vector with initial point <math>(a, b)</math> and coordinates <math>v_1</math> and <math>v_2</math>.] | ||

The '''length''' of a vector <math>\mbox | The '''length''' of a vector <math>\mbox{\bf{v}} = (P, Q)</math> in <math>R^2</math> is denoted by <math>|\mbox{\bf{v}}|</math> and defined by | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

|\mbox | |\mbox{\bf{v}}| = distance(P, Q). | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

If <math>P = (a, b)</math> and <math>Q = (c, d)</math>, then the formula for the distance between two points implies that | If <math>P = (a, b)</math> and <math>Q = (c, d)</math>, then the formula for the distance between two points implies that | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

|\mbox | |\mbox{\bf{v}}| = \sqrt{(c - a)^2 + (d - b)^2} . | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

From equations (1) it follows that the coordinates of the vector <math>\mbox | From equations (1) it follows that the coordinates of the vector <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> are the two numbers <math>v_1 = c - a</math> and <math>v_2 = d - b</math>. Hence | ||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-1|The length of any vector <math>\mbox | {{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-1|The length of any vector <math>\mbox{\bf{v}} = (v_1, v_2)_P</math> is given by | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

|\mbox | |\mbox{\bf{v}}|= \sqrt {v_1^2 + v_2^2} . | ||

</math>|}} | </math>|}} | ||

Thus the length of a vector depends only on its coordinates. | Thus the length of a vector depends only on its coordinates. | ||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

<div id="fig 10.11" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | <div id="fig 10.11" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | ||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig10_11.png | | [[File:guide_c5467_scanfig10_11.png | 600px | thumb | ]] | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

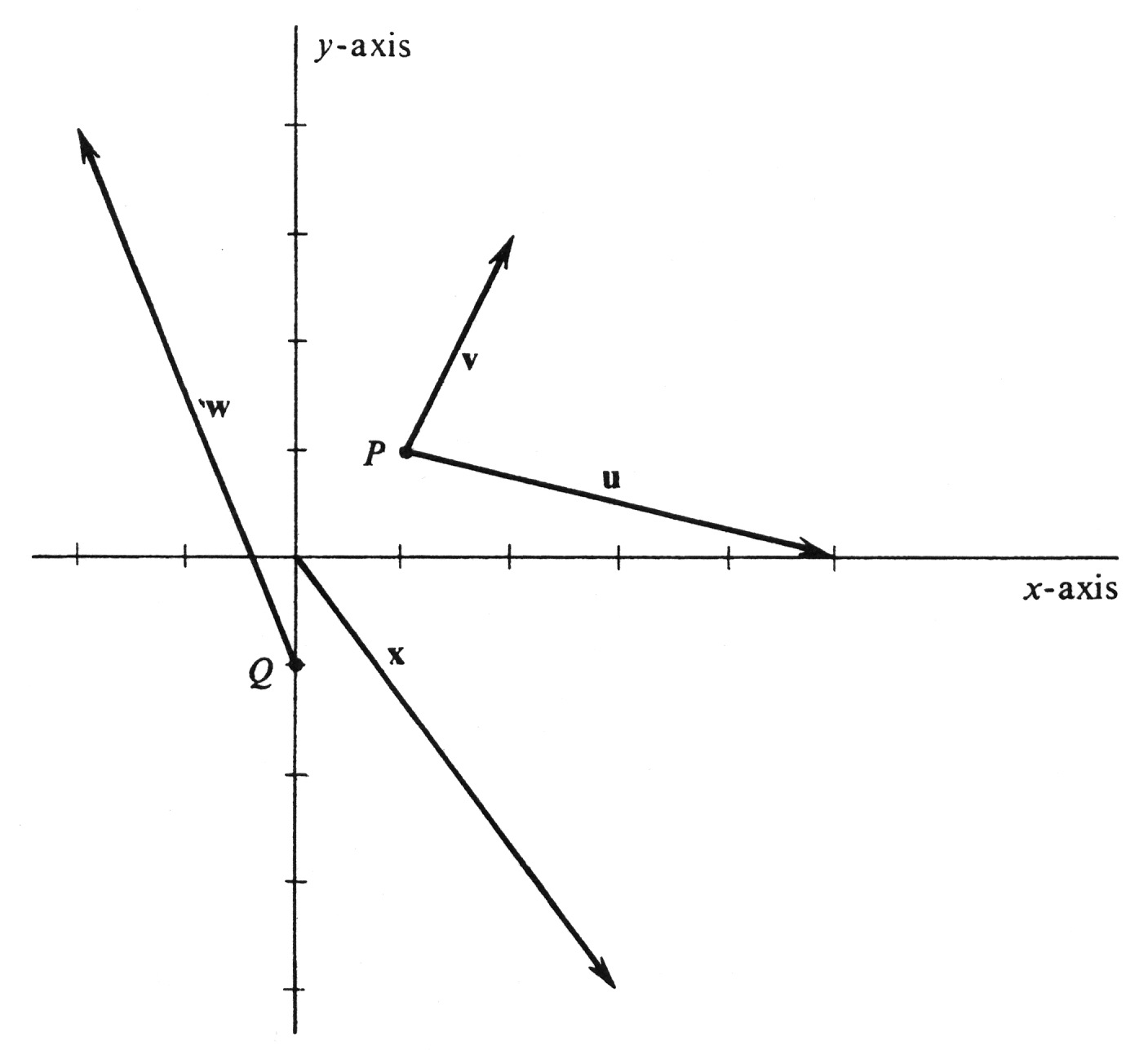

The vectors are drawn in Figure 11. Their respective lengths, computed from the formula in (3.1), are | The vectors are drawn in Figure 11. Their respective lengths, computed from the formula in (3.1), are | ||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

\begin{eqnarray*} | \begin{eqnarray*} | ||

|\mbox | |\mbox{\bf{v}}| &=& \sqrt{1^2 + 2^2} = \sqrt{5}, \\ | ||

|\mbox | |\mbox{\bf{u}}| &=& \sqrt{4^2 + (-1)^2} = \sqrt{17}, \\ | ||

|\mbox | |\mbox{\bf{w}}| &=& \sqrt{(-2)^2 + 5^2} = \sqrt{29},\\ | ||

|\mbox | |\mbox{\bf{x}}| &=& \sqrt{3^2 + (-4)^2} = \sqrt{25} = 5. | ||

\end{eqnarray*} | \end{eqnarray*} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| Line 126: | Line 126: | ||

We shall denote the set of all vectors in <math>R^2</math> by <math>\mathcal{V}</math>. For every point <math>P</math> in <math>R^2</math>, the subset of <math>\mathcal{V}</math> consisting of all vectors with initial point <math>P</math> will be denoted by | We shall denote the set of all vectors in <math>R^2</math> by <math>\mathcal{V}</math>. For every point <math>P</math> in <math>R^2</math>, the subset of <math>\mathcal{V}</math> consisting of all vectors with initial point <math>P</math> will be denoted by | ||

<math>\mathcal{V}_P</math>. We shall now define, in each set <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math>, an operation of addition of vectors and an operation of multiplication of vectors by real numbers. | <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math>. We shall now define, in each set <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math>, an operation of addition of vectors and an operation of multiplication of vectors by real numbers. | ||

Addition in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> is defined as follows: If <math>\mbox | Addition in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> is defined as follows: If <math>\mbox{\bf{u}} = (u_1, u_2)_P</math> and <math>\mbox{\bf{v}} = (v_1, v_2)_P</math> are any two vectors in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math>, then their sum <math>\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}</math> is the vector defined by | ||

<span id{{=}}"eq10.3.3"/> | <span id{{=}}"eq10.3.3"/> | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

\begin{equation} | \begin{equation} | ||

\mbox | \mbox{\bf{u} + \bf{v}} = (u_1 +v_1,u_2 + v_2)_P. | ||

\label{eq10.3.3} | \label{eq10.3.3} | ||

\end{equation} | \end{equation} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

Note that the sum of two vectors in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> is again a vector in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math>. Furthermore, if <math>\mbox | Note that the sum of two vectors in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> is again a vector in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math>. Furthermore, if <math>\mbox{\bf{u}}</math> is in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> and <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> is in <math>\mathcal{V}_Q</math>, then their sum is not defined unless <math>P = Q</math>. That is, ''the sum of two vectors is defined if and only if they have the same initial point.'' For every vector <math>\mbox{\bf{v}} = (v_1, v_2)_P</math>, we denote the vector <math>(-v_1, -v_2)_P</math> by <math>-\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>. In this way, subtraction of vectors in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> is defined by the equation | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

\mbox | \mbox{\bf{u}} - \mbox{\bf{v}} = \mbox{\bf{u}} + (-\mbox{\bf{v}}), | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| Line 146: | Line 146: | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

\begin{equation} | \begin{equation} | ||

\mbox | \mbox{\bf{u}} - \mbox{\bf{v}} = (u_1 - v_1, u_2 - v_2)_P. | ||

\label{eq10.3.4} | \label{eq10.3.4} | ||

\end{equation} | \end{equation} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

The unique vector in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> with both coordinates equal to zero is called the zero vector and will be denoted by <math>\mbox | The unique vector in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> with both coordinates equal to zero is called the zero vector and will be denoted by <math>\mbox{\bf{0}}</math>. Thus | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

\mbox | \mbox{\bf{0}} = (0, 0)_P = (P, P). | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| Line 160: | Line 160: | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

\begin{eqnarray*} | \begin{eqnarray*} | ||

\mbox | \mbox{\bf{v}} + \mbox{\bf{0}} &=& \mbox{\bf{v}}, \\ | ||

\mbox | \mbox{\bf{v}} - \mbox{\bf{v}} &=& \mbox{\bf{0}} | ||

\end{eqnarray*} | \end{eqnarray*} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

are true for every vector <math>\mbox | are true for every vector <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math>. Geometrically the zero vector in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> is represented simply by the point <math>P</math>. Of course, there are as many different zero vectors as there are points in the plane, and one cannot tell from the notation <math>\mbox{\bf{0}}</math> to which set <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> a given zero vector belongs. It is obvious that every zero vector has length zero. Conversely, the length of a nonzero vector must be positive, since at least one of its coordinates is not zero. Hence | ||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-2|A vector <math>\mbox | {{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-2|A vector <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> is a zero vector if and only if <math>|\mbox{\bf{v}}| = 0</math>.|}} | ||

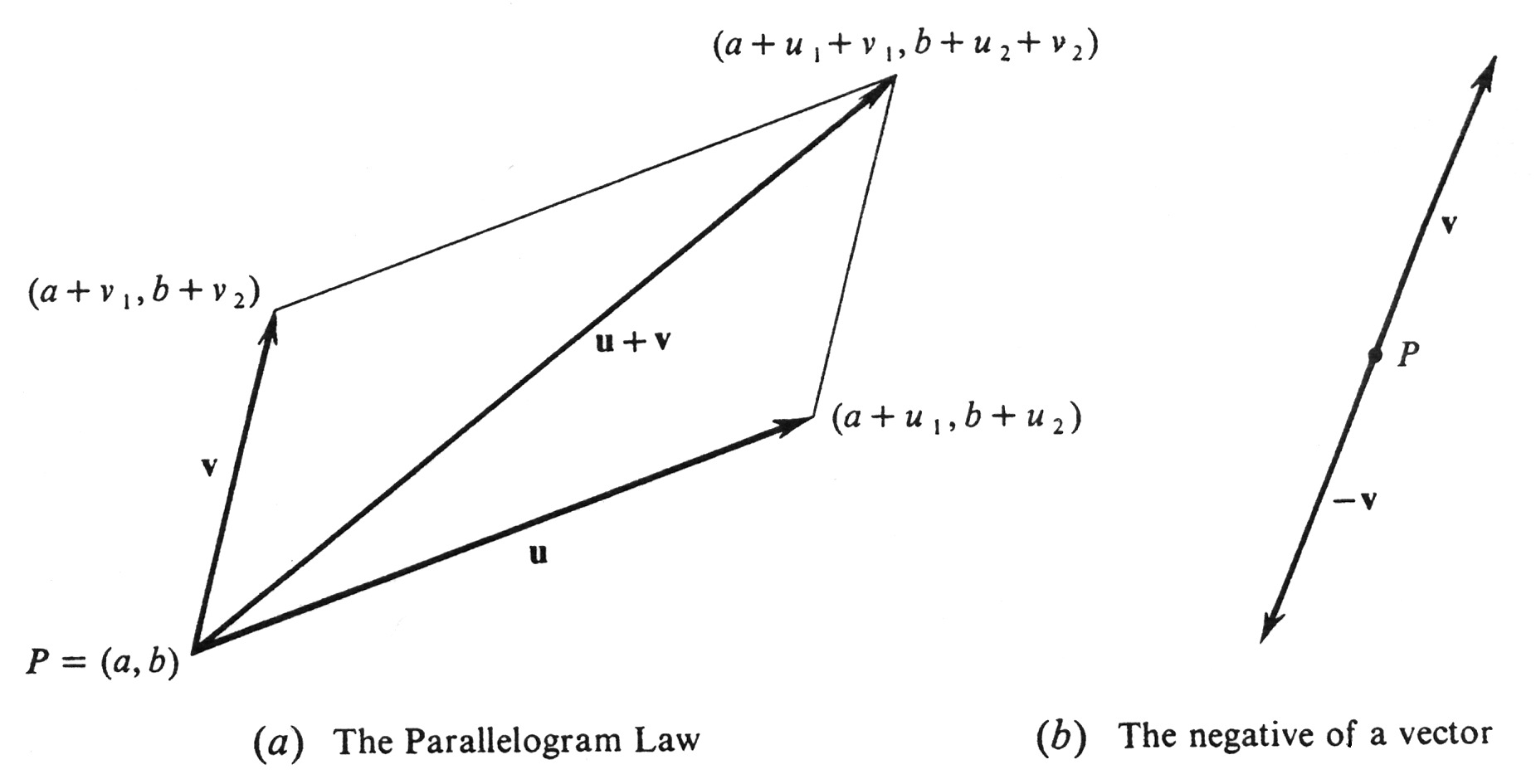

Geometrically, the sum <math>\mbox | Geometrically, the sum <math>\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}</math> of two nonzero vectors <math>\mbox{\bf{u}}</math> and <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> is the vector in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> which is a diagonal of the parallelogram which has <math>\mbox{\bf{u}}</math> and <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> as sides. This is the famous Parallelogram Law and is illustrated in Figure 12(a). It can be verified in a straightforward way by computing the slopes of the various line segments, and we omit the details. Similarly, the vector <math>-\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> is represented geometrically as a directed line segment Iying in the | ||

same straight line as <math>\mbox | same straight line as <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>, but in the opposite direction, as shown in Figure 12(b). Moreover, the vectors <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> and <math>-\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> have the same length, since | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

|\mbox | |\mbox{\bf{v}}| = \sqrt{v_1^2+v_2^2} = \sqrt{(-v_1)^2 + (-v_2)^2} = | ||

|- \mbox | |- \mbox{\bf{v}}|. | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

<div id="fig 10.12" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | <div id="fig 10.12" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | ||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig10_12.png | | [[File:guide_c5467_scanfig10_12.png | 600px | thumb | ]] | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

The second algebraic operation in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> is defined as follows: For every real number <math>a</math> and every vector <math>\mbox | The second algebraic operation in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> is defined as follows: For every real number <math>a</math> and every vector <math>\mbox{\bf{v}} = (v_1, v_2)_P</math> in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math>, we define a vector <math>a\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>, called the '''product''' of <math>a</math> and <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>, by the equation | ||

<span id{{=}}"eq10.3.5"/> | <span id{{=}}"eq10.3.5"/> | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

\begin{equation} | \begin{equation} | ||

a\mbox | a\mbox{\bf{v}} = (av_1, av_2)_P . | ||

\label{eq10.3.5} | \label{eq10.3.5} | ||

\end{equation} | \end{equation} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

In traditional vector terminology, the real number <math>a</math> is called a '''scalar.''' Note that we have ''not'' defined a product of two vectors. If we compute the length of the vector <math>a\mbox | In traditional vector terminology, the real number <math>a</math> is called a '''scalar.''' Note that we have ''not'' defined a product of two vectors. If we compute the length of the vector <math>a\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>, we find that | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

\begin{eqnarray*} | \begin{eqnarray*} | ||

|a\mbox | |a\mbox{\bf{v}}| &=& \sqrt{(av_1)^2 + (av_2)^2} = \sqrt{a^2(v_1^2 + v_2^2)}\\ | ||

&=& |a| \sqrt{v_1^2 + v_2^2} = |a| |\mbox | &=& |a| \sqrt{v_1^2 + v_2^2} = |a| |\mbox{\bf{v}}|, | ||

\end{eqnarray*} | \end{eqnarray*} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| Line 198: | Line 198: | ||

a result which we summarize in the statement | a result which we summarize in the statement | ||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-3|<math>|a\mbox | {{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-3|<math>|a\mbox{\bf{v}}| = |a| \; |\mbox{\bf{v}}|</math>, for every real num ber <math>a</math> and every vector <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>.|}} | ||

If <math>\mbox | If <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> is an arbitrary nonzero vector in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> and if <math>a \neq 0</math>, then the slope of the line segment joining <math>P</math> to the terminal point of <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> is the same as that joining <math>P</math> to the terminal point of <math>a\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>. Hence <math>P</math> and the terminal points of <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> and <math>a\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> lie on the same straight line. In addition, it is easy to check that the arrows representing <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> and <math>a\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> are in the same or opposite direction according as a is positive or negative. | ||

<span id="fig 10.13"/> | <span id="fig 10.13"/> | ||

'''Example''' | '''Example''' | ||

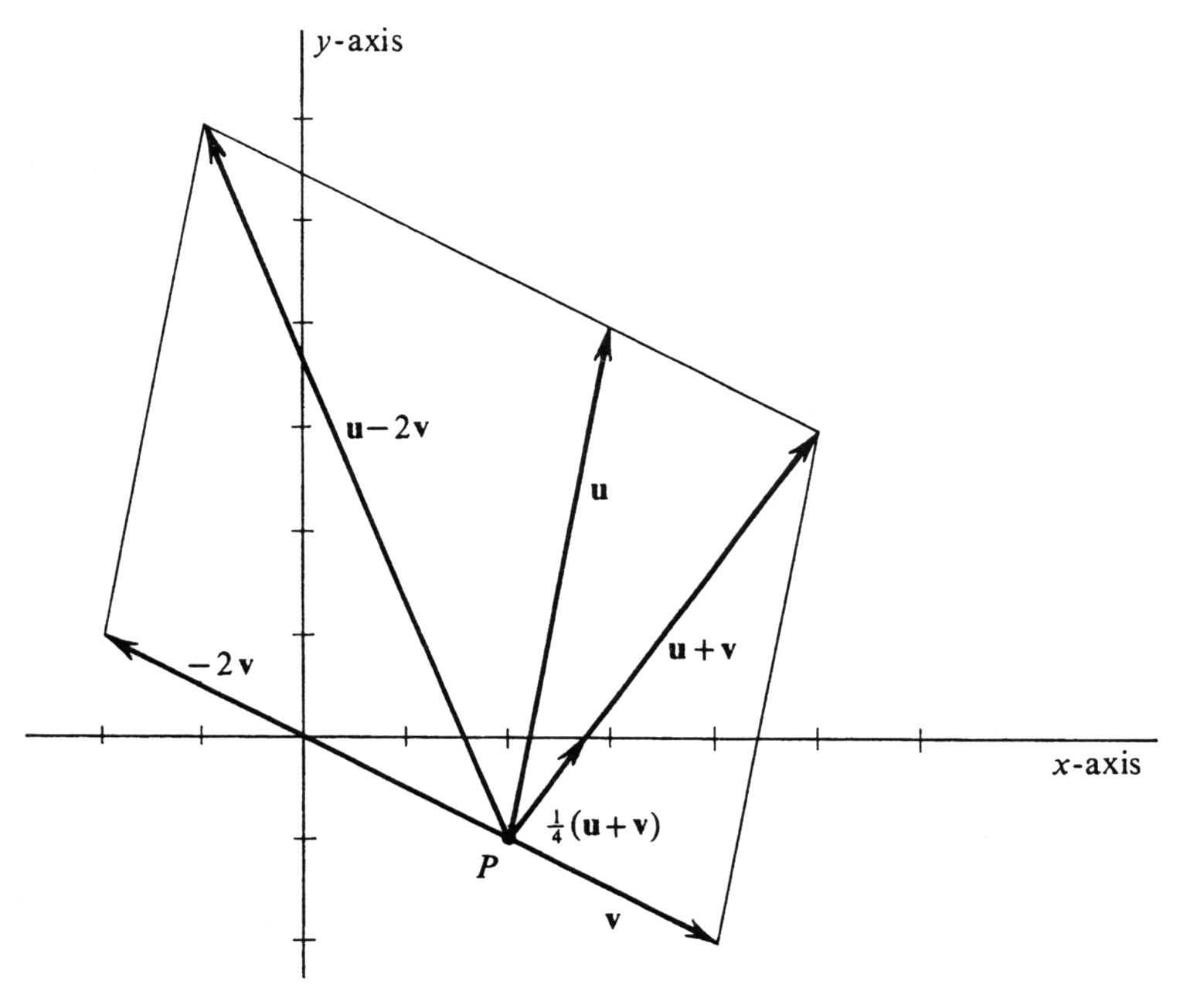

Let <math>P = (2, -1)</math> and consider the two vectors <math>\mbox | Let <math>P = (2, -1)</math> and consider the two vectors <math>\mbox{\bf{u}} = (1, 5)_P</math> and <math>\mbox{\bf{v}} = (2, -1)_P</math>. Compute and draw each of the following vectors in the same plane with <math>\mbox{\bf{u}}</math> and <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>. | ||

<ul style="list-style-type:lower-alpha"> | <ul style="list-style-type:lower-alpha"> | ||

<li> <math>\mbox | <li> <math>\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}, </math></li> | ||

<li><math>-2\mbox | <li><math>-2\mbox{\bf{v}},</math></li> | ||

<li><math>\mbox | <li><math>\mbox{\bf{u}} - 2\mbox{\bf{v}},</math></li> | ||

<li><math>\frac{1}{4}(\mbox | <li><math>\frac{1}{4}(\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}).</math></li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

| Line 217: | Line 217: | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

\begin{eqnarray*} | \begin{eqnarray*} | ||

\mbox | \mbox{\bf{u} + \bf{v}} &=& (1, 5)_P + (2, -1)_P = (3, 4)_P, \\ | ||

-2\mbox | -2\mbox{\bf{v}} &=& - 2(2, -1)_P = (-4, 2)_P, \\ | ||

\mbox | \mbox{\bf{u}} - 2\mbox{\bf{v}} &=& (1, 5)_P - 2(2, -1)_P \\ | ||

&=& (1, 5)_P + (-4, 2)_P = (-3, 7)_P, \\ | &=& (1, 5)_P + (-4, 2)_P = (-3, 7)_P, \\ | ||

\frac{1}{4}(\mbox | \frac{1}{4}(\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}) &=& \frac{1}{4}(3, 4)_P = (\frac{3}{4}, 1)_P. | ||

\end{eqnarray*} | \end{eqnarray*} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| Line 229: | Line 229: | ||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig10_13.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | [[File:guide_c5467_scanfig10_13.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

The directed line segments representing these vectors, as well as <math>\mbox | The directed line segments representing these vectors, as well as <math>\mbox{\bf{u}}</math> and <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>, are shown in Figure 13. The easiest way to draw them is to make a list of their terminal points. We recall that a vector with coordinates <math>v_1</math> and <math>v_2</math> and | ||

initial point <math>P = (a, b)</math> has a terminal point equal to <math>(a + v_1, b + v_2)</math>. Hence | initial point <math>P = (a, b)</math> has a terminal point equal to <math>(a + v_1, b + v_2)</math>. Hence | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

\begin{array}{ll} | \begin{array}{ll} | ||

\mathrm{terminal~point~of~\bf{u}} &= (2 + 1, -1 + 5) = (3, 4), | \mathrm{terminal~point~of~\bf{u}} &= (2 + 1, -1 + 5) = (3, 4), \\ | ||

\mathrm{terminal~point~of~\bf{v}} &= (2 + 2, -1 - 1) = (4, -2), \\ | \mathrm{terminal~point~of~\bf{v}} &= (2 + 2, -1 - 1) = (4, -2), \\ | ||

\mathrm{terminal~point~of~\bf{u}} + \mathrm | \mathrm{terminal~point~of~\bf{u}} + \mathrm{\bf{v}} &= (2 + 3, -1 + 4) = (5, 3), \\ | ||

\mathrm{terminal~point~of~ -2\bf{v}} &= (2 - 4, -1 + 2) = (-2, 1), \\ | \mathrm{terminal~point~of~ -2\bf{v}} &= (2 - 4, -1 + 2) = (-2, 1), \\ | ||

\mathrm{terminal~point~of~\bf{u}} - 2\mathrm | \mathrm{terminal~point~of~\bf{u}} - 2\mathrm{\bf{v}} &= (2 - 3, -1 + 7) = (-1, 6),\\ | ||

\mathrm{terminal~point~of~} \frac{1}{4}(\mathrm | \mathrm{terminal~point~of~} \frac{1}{4}(\mathrm{\bf{u} + \bf{v}}) &= (2 + \frac{3}{4}, -1 + 1) = (2\frac{3}{4}, 0). | ||

\end{array} | \end{array} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

| Line 252: | Line 252: | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

\mbox | \mbox{\bf{u}} + (\mbox{\bf{v}} + \mbox{\bf{w}}) = (\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}) + \mbox{\bf{w}}\;\;\; \mbox{and}\;\;\; (ab)\mbox{\bf{v}} = a(b\mbox{\bf{v}}). | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

| Line 259: | Line 259: | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

\mbox | \mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}} = \mbox{\bf{v}} + \mbox{\bf{u}}. | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

| Line 266: | Line 266: | ||

EXISTENCE OF ADDITIVE IDENTITY | EXISTENCE OF ADDITIVE IDENTITY | ||

There exists a vector <math>\mbox | There exists a vector <math>\mbox{\bf{0}}</math> in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> with the property that <math>\mbox{\bf{v}} + \mbox{\bf{0}} = \mbox{\bf{v}}</math>, for every vector <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math>. | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

<li> | <li> | ||

EXISTENCE OF SUBTRACTION | EXISTENCE OF SUBTRACTION | ||

For every vector <math>\mbox | For every vector <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math>, there exists a vector <math>-\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> such that <math>\mbox{\bf{v}} + (-\mbox{\bf{v}}) = \mbox{\bf{0}}</math>. | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

<li> | <li> | ||

| Line 276: | Line 276: | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

a(\mbox | a(\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}) = a\mbox{\bf{u}} + a\mbox{\bf{v}} \;\;\;\mbox{and}\;\;\; (a + b)\mbox{\bf{v}} = a\mbox{\bf{v}} + b\mbox{\bf{v}}. | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

| Line 282: | Line 282: | ||

EXISTENCE OF SCALAR IDENTITY | EXISTENCE OF SCALAR IDENTITY | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

1\mbox | 1\mbox{\bf{v}} = \mbox{\bf{v}}. | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

| Line 288: | Line 288: | ||

|}} | |}} | ||

The proof of this theorem follows easily from the definitions of vector addition and scalar multiplication, from the definitions of <math>\mbox | The proof of this theorem follows easily from the definitions of vector addition and scalar multiplication, from the definitions of <math>\mbox{\bf{0}}</math> and <math>-\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>, and from the corresponding properties of addition and multiplication of real | ||

numbers given on page 2. The importance of the theorem is that every algebraic fact about vectors can be derived from the six properties listed. In fact, in abstract algebra, these properties are taken as a set of axioms: An arbitrary set <math>\mbox | numbers given on page 2. The importance of the theorem is that every algebraic fact about vectors can be derived from the six properties listed. In fact, in abstract algebra, these properties are taken as a set of axioms: An arbitrary set <math>\mbox{\bf{V}}</math> is called a '''vector space''' and its elements are called '''vectors''' if, for every pair of elements <math>\mbox{\bf{u}}</math> and <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> in <math>\mbox{\bf{V}}</math> and for every real number a, an element <math>\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}</math> and an element <math>a\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> in <math>\mbox{\bf{V}}</math> are defined so that conditions (i) through (vi) are satisfied. This definition has proved to be of enormous value in mathematics and examples of vector spaces occur over and over again. In particular, Theorem (3.4) asserts that, for each point <math>P</math> in <math>R^2</math>, the set <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math> is a vector space. | ||

'''Example''' | '''Example''' | ||

Let <math>\mbox | Let <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> be a nonzero vector in <math>R^2</math>. Then the set, which we shall denote by <math>R\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>, consisting of all products <math>t\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>, where <math>t</math> is a real number, is an example of a vector space. For, if <math>P</math> is the initial point of <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>, then <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> lies in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math>, and it follows that every product <math>t\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> also lies in <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math>. Hence the sum of any two vectors in <math>R\bf{v}</math> is defined, and, since | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

t\mbox | t\mbox{\bf{v}} + s\mbox{\bf{v}} = (t + s)\mbox{\bf{v}}, | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

the sum is again in <math>R\mbox | the sum is again in <math>R\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>. Similarly, if <math>t\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> is in <math>R\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> and if <math>s</math> is any real number, then | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

s(t \mbox | s(t \mbox{\bf{v}})= (st)\mbox{\bf{v}}, | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

and <math>(st)\mbox | and <math>(st)\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> is by definition in <math>R\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>. Thus vector addition and scalar multiplication are defined in the set <math>R\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>. Conditions (i), (ii), (v), and (vi) are automatically satisfied because they hold in the larger set <math>\mathcal{V}_P</math>. | ||

Finally, conditions (iii) and (iv) are also satisfied, since | Finally, conditions (iii) and (iv) are also satisfied, since | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

\mbox | \mbox{\bf{0}} = 0\mbox{\bf{v}} \;\;\;\mbox{and}\;\;\; - \mbox{\bf{v}} = (-1)\mbox{\bf{v}}. | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

This completes the proof that <math>R\mbox | This completes the proof that <math>R\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> is a vector space. The terminal points of all the vectors in <math>R\mbox{\bf{v}}</math> form the straight line containing the initial and terminal points of the vector <math>\mbox{\bf{v}}</math>. | ||

==General references== | ==General references== | ||

{{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | {{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | ||

Latest revision as of 18:33, 22 November 2024

A vector in the plane is an ordered pair [math](P, Q)[/math] of points in the plane. The point [math]P[/math] is called the initial point of the vector and [math]Q[/math] the terminal point. Geometrically, the vector [math](P, Q)[/math] will be represented as a directed line segment, or arrow, from [math]P[/math] to [math]Q[/math], as illustrated in Figure 10. We shall use boldface lower-case letters to denote vectors. For example, if [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is the vector with initial point [math]P[/math] and terminal point [math]Q[/math], then [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} = (P, Q)[/math].

Having identified the plane with the set [math]R^2[/math] of all ordered pairs of real numbers, we see that a vector is determined by four real numbers: two coordinates of its initial point, and two of its terminal point. Let [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] be a vector with initial point [math]P = (a, b)[/math] and terminal point [math]Q = (c, d)[/math]. Then the two numbers [math]v_1[/math] and [math]v_2[/math] given by the equations

are defined to be first and second coordinates, respectively, of the vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]R^2[/math]. Thus we have defined coordinates of a vector in [math]R^2[/math] as well as coordinates of a point in [math]R^2[/math]. The definitions are not the same, although the concepts are certainly related.

If a vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] has initial point [math]P = (a, b)[/math] and coordinates [math]v_1[/math] and [math]v_2[/math], then equations (1) tell us that the terminal point [math]Q = (c, d)[/math] is given by

It follows that a vector is completely determined by its initial point and its coordinates. Hence, another notation for a vector, which we shall use, is \setcounter{equation}{1}

[Although it would be consistent with this notation, we shall not write [math](v_1, v_2)_{(a,b)}[/math] for the vector with initial point [math](a, b)[/math] and coordinates [math]v_1[/math] and [math]v_2[/math].] The length of a vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} = (P, Q)[/math] in [math]R^2[/math] is denoted by [math]|\mbox{\bf{v}}|[/math] and defined by

If [math]P = (a, b)[/math] and [math]Q = (c, d)[/math], then the formula for the distance between two points implies that

From equations (1) it follows that the coordinates of the vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] are the two numbers [math]v_1 = c - a[/math] and [math]v_2 = d - b[/math]. Hence

The length of any vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} = (v_1, v_2)_P[/math] is given by

Thus the length of a vector depends only on its coordinates.

Example

Find the terminal point of each of the following vectors. Draw each one as an arrow in the [math]xy[/math]-plane, and compute its length.

- [math]\textbf{v}\; = (1, 2)_P, \;\;\mathrm{where}\; P = (1, 1),[/math]

- [math]\textbf{u}\; = (4, -1)_P, \;\;\mathrm{where}\; P = (1, 1),[/math]

- [math]\textbf{w}\; = (-2, 5)_Q,\;\;\mathrm{where}\; Q = (0, -1),[/math]

- [math]\textbf{x}\; = (3, -4)_O, \;\;\mathrm{where}\; O = (0, 0).[/math]

We have seen that, if [math]P = (a, b)[/math], then the terminal point of the vector [math](v_1, v_2)_P[/math] is the ordered pair [math](a + v_1, b + v_2)[/math]. It follows that

The vectors are drawn in Figure 11. Their respective lengths, computed from the formula in (3.1), are

We shall denote the set of all vectors in [math]R^2[/math] by [math]\mathcal{V}[/math]. For every point [math]P[/math] in [math]R^2[/math], the subset of [math]\mathcal{V}[/math] consisting of all vectors with initial point [math]P[/math] will be denoted by

[math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math]. We shall now define, in each set [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math], an operation of addition of vectors and an operation of multiplication of vectors by real numbers.

Addition in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] is defined as follows: If [math]\mbox{\bf{u}} = (u_1, u_2)_P[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} = (v_1, v_2)_P[/math] are any two vectors in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math], then their sum [math]\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is the vector defined by

Note that the sum of two vectors in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] is again a vector in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math]. Furthermore, if [math]\mbox{\bf{u}}[/math] is in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is in [math]\mathcal{V}_Q[/math], then their sum is not defined unless [math]P = Q[/math]. That is, the sum of two vectors is defined if and only if they have the same initial point. For every vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} = (v_1, v_2)_P[/math], we denote the vector [math](-v_1, -v_2)_P[/math] by [math]-\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math]. In this way, subtraction of vectors in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] is defined by the equation

which implies the following companion formula to (3):

The unique vector in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] with both coordinates equal to zero is called the zero vector and will be denoted by [math]\mbox{\bf{0}}[/math]. Thus

Obviously, the equations

are true for every vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math]. Geometrically the zero vector in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] is represented simply by the point [math]P[/math]. Of course, there are as many different zero vectors as there are points in the plane, and one cannot tell from the notation [math]\mbox{\bf{0}}[/math] to which set [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] a given zero vector belongs. It is obvious that every zero vector has length zero. Conversely, the length of a nonzero vector must be positive, since at least one of its coordinates is not zero. Hence

A vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is a zero vector if and only if [math]|\mbox{\bf{v}}| = 0[/math].

Geometrically, the sum [math]\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] of two nonzero vectors [math]\mbox{\bf{u}}[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] is the vector in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] which is a diagonal of the parallelogram which has [math]\mbox{\bf{u}}[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] as sides. This is the famous Parallelogram Law and is illustrated in Figure 12(a). It can be verified in a straightforward way by computing the slopes of the various line segments, and we omit the details. Similarly, the vector [math]-\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is represented geometrically as a directed line segment Iying in the same straight line as [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], but in the opposite direction, as shown in Figure 12(b). Moreover, the vectors [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] and [math]-\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] have the same length, since

The second algebraic operation in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] is defined as follows: For every real number [math]a[/math] and every vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} = (v_1, v_2)_P[/math] in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math], we define a vector [math]a\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], called the product of [math]a[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], by the equation

In traditional vector terminology, the real number [math]a[/math] is called a scalar. Note that we have not defined a product of two vectors. If we compute the length of the vector [math]a\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], we find that

a result which we summarize in the statement

[math]|a\mbox{\bf{v}}| = |a| \; |\mbox{\bf{v}}|[/math], for every real num ber [math]a[/math] and every vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math].

If [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is an arbitrary nonzero vector in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] and if [math]a \neq 0[/math], then the slope of the line segment joining [math]P[/math] to the terminal point of [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is the same as that joining [math]P[/math] to the terminal point of [math]a\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math]. Hence [math]P[/math] and the terminal points of [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] and [math]a\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] lie on the same straight line. In addition, it is easy to check that the arrows representing [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] and [math]a\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] are in the same or opposite direction according as a is positive or negative.

Example

Let [math]P = (2, -1)[/math] and consider the two vectors [math]\mbox{\bf{u}} = (1, 5)_P[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} = (2, -1)_P[/math]. Compute and draw each of the following vectors in the same plane with [math]\mbox{\bf{u}}[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math].

- [math]\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}, [/math]

- [math]-2\mbox{\bf{v}},[/math]

- [math]\mbox{\bf{u}} - 2\mbox{\bf{v}},[/math]

- [math]\frac{1}{4}(\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}).[/math]

The computations are very simple:

The directed line segments representing these vectors, as well as [math]\mbox{\bf{u}}[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], are shown in Figure 13. The easiest way to draw them is to make a list of their terminal points. We recall that a vector with coordinates [math]v_1[/math] and [math]v_2[/math] and initial point [math]P = (a, b)[/math] has a terminal point equal to [math](a + v_1, b + v_2)[/math]. Hence

The next theorem summarizes the algebraic facts about the set [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] of all vectors in the plane with initial point [math]P[/math].

For each point [math]P[/math] in [math]R^2[/math], vector addition and scalar multiplication in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] have the following properties:

-

ASSOCIATIVITY

[[math]] \mbox{\bf{u}} + (\mbox{\bf{v}} + \mbox{\bf{w}}) = (\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}) + \mbox{\bf{w}}\;\;\; \mbox{and}\;\;\; (ab)\mbox{\bf{v}} = a(b\mbox{\bf{v}}). [[/math]]

-

COMMUTATIVITY

[[math]] \mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}} = \mbox{\bf{v}} + \mbox{\bf{u}}. [[/math]]

- EXISTENCE OF ADDITIVE IDENTITY There exists a vector [math]\mbox{\bf{0}}[/math] in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] with the property that [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} + \mbox{\bf{0}} = \mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], for every vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math].

- EXISTENCE OF SUBTRACTION For every vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math], there exists a vector [math]-\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] such that [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} + (-\mbox{\bf{v}}) = \mbox{\bf{0}}[/math].

-

DISTRIBUTIVITY

[[math]] a(\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}) = a\mbox{\bf{u}} + a\mbox{\bf{v}} \;\;\;\mbox{and}\;\;\; (a + b)\mbox{\bf{v}} = a\mbox{\bf{v}} + b\mbox{\bf{v}}. [[/math]]

-

EXISTENCE OF SCALAR IDENTITY

[[math]] 1\mbox{\bf{v}} = \mbox{\bf{v}}. [[/math]]

The proof of this theorem follows easily from the definitions of vector addition and scalar multiplication, from the definitions of [math]\mbox{\bf{0}}[/math] and [math]-\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], and from the corresponding properties of addition and multiplication of real numbers given on page 2. The importance of the theorem is that every algebraic fact about vectors can be derived from the six properties listed. In fact, in abstract algebra, these properties are taken as a set of axioms: An arbitrary set [math]\mbox{\bf{V}}[/math] is called a vector space and its elements are called vectors if, for every pair of elements [math]\mbox{\bf{u}}[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]\mbox{\bf{V}}[/math] and for every real number a, an element [math]\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] and an element [math]a\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]\mbox{\bf{V}}[/math] are defined so that conditions (i) through (vi) are satisfied. This definition has proved to be of enormous value in mathematics and examples of vector spaces occur over and over again. In particular, Theorem (3.4) asserts that, for each point [math]P[/math] in [math]R^2[/math], the set [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] is a vector space.

Example

Let [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] be a nonzero vector in [math]R^2[/math]. Then the set, which we shall denote by [math]R\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], consisting of all products [math]t\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], where [math]t[/math] is a real number, is an example of a vector space. For, if [math]P[/math] is the initial point of [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], then [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] lies in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math], and it follows that every product [math]t\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] also lies in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math]. Hence the sum of any two vectors in [math]R\bf{v}[/math] is defined, and, since

the sum is again in [math]R\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math]. Similarly, if [math]t\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is in [math]R\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] and if [math]s[/math] is any real number, then

and [math](st)\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is by definition in [math]R\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math]. Thus vector addition and scalar multiplication are defined in the set [math]R\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math]. Conditions (i), (ii), (v), and (vi) are automatically satisfied because they hold in the larger set [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math]. Finally, conditions (iii) and (iv) are also satisfied, since

This completes the proof that [math]R\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is a vector space. The terminal points of all the vectors in [math]R\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] form the straight line containing the initial and terminal points of the vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math].

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.