guide:025784032f: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="d-none"><math> | |||

\newcommand{\ex}[1]{\item } | |||

\newcommand{\sx}{\item} | |||

\newcommand{\x}{\sx} | |||

\newcommand{\sxlab}[1]{} | |||

\newcommand{\xlab}{\sxlab} | |||

\newcommand{\prov}[1] {\quad #1} | |||

\newcommand{\provx}[1] {\quad \mbox{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\intext}[1]{\quad \mbox{#1} \quad} | |||

\newcommand{\R}{\mathrm{\bf R}} | |||

\newcommand{\Q}{\mathrm{\bf Q}} | |||

\newcommand{\Z}{\mathrm{\bf Z}} | |||

\newcommand{\C}{\mathrm{\bf C}} | |||

\newcommand{\dt}{\textbf} | |||

\newcommand{\goesto}{\rightarrow} | |||

\newcommand{\ddxof}[1]{\frac{d #1}{d x}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddx}{\frac{d}{dx}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddt}{\frac{d}{dt}} | |||

\newcommand{\dydx}{\ddxof y} | |||

\newcommand{\nxder}[3]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{d{#3}^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\deriv}[2]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{dx^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\dist}{\mathrm{distance}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccot}{\mathrm{arccot\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccsc}{\mathrm{arccsc\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsec}{\mathrm{arcsec\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arctanh}{\mathrm{arctanh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsinh}{\mathrm{arcsinh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccosh}{\mathrm{arccosh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\sech}{\mathrm{sech\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\csch}{\mathrm{csch\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\conj}[1]{\overline{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb} | |||

</math></div> | |||

==<span id="sec 2.3"></span>Rates of Change with respect to Time.== | |||

The values of many physical quantities depend on time and change with time. In a mathematical formulation such a quantity is usually denoted by a variable which is a function of time. In this section we are concerned with the instantaneous rates of change of time-dependent variables. Let <math>u</math> be a real-valued function of a real variable <math>t</math>, where we identify <math>t</math> with time. The rate of change of <math>u</math> with respect to time at a given instant <math>t = a</math> can be determined by considering the derivative of <math>u</math>. We have already observed in Chapter 1 that the derivative <math>f'(a)</math> of a function <math>f</math> at a particular number <math>a</math> is the rate of change of the value <math>f(x)</math> of the function <math>f</math> with respect to <math>x</math> at <math>a</math>. It follows that the instantaneous rate of change of <math>u</math> with respect to time, when <math>t = a</math>, is equal to the derivative: | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

u'(a) = \frac{du}{dt} (a) = \lim_{d \rightarrow 0}\frac{u(a + d) - u(a)}{d}. | |||

</math> | |||

In a physical application the variable <math>u</math> might denote the number of gallons of water in a tank at time <math>t</math>, where <math>t</math> is measured in minutes. Then, <math>\frac{d}{du}(a)</math> is equal to the rate at which water is flowing in or out of the tank at time <math>t = a</math> and is measured in gallons per minute. If <math>\frac{d}{du}(a)</math> is positive, then the quantity of water in the tank is increasing when <math>t = a</math> and water is flowing into the tank. On the other hand, if <math>\frac{d}{du}(a)</math> is negative, then the amount of water is decreasing at that moment and water is draining out. Finally, if <math>\frac{d}{du}(a) = 0</math>, then the amount is not changing | |||

at <math>t = a</math>. | |||

An important example of rate of change with respect to time is velocity. For example, consider a car in motion on a straight road. To formulate the situation mathematically, we identify the road with a real number line, the car with a point on the line, and the location of the car at time <math>t</math> with the coordinate <math>s(t)</math> of the point on the line. Thus, <math>s</math> is a real-valued function of | |||

the real variable <math>t</math>. The '''average velocity''' during the time interval from <math>t = a</math> to <math>t = a + d</math> is equal to the change in position divided by the change in time. Denoting this quantity by <math>v_{av}</math>, we have | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

v_{av} = \frac{s(a + d) - s(a)}{d}. | |||

</math> | |||

<div id="fig 2.15" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig2_15.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

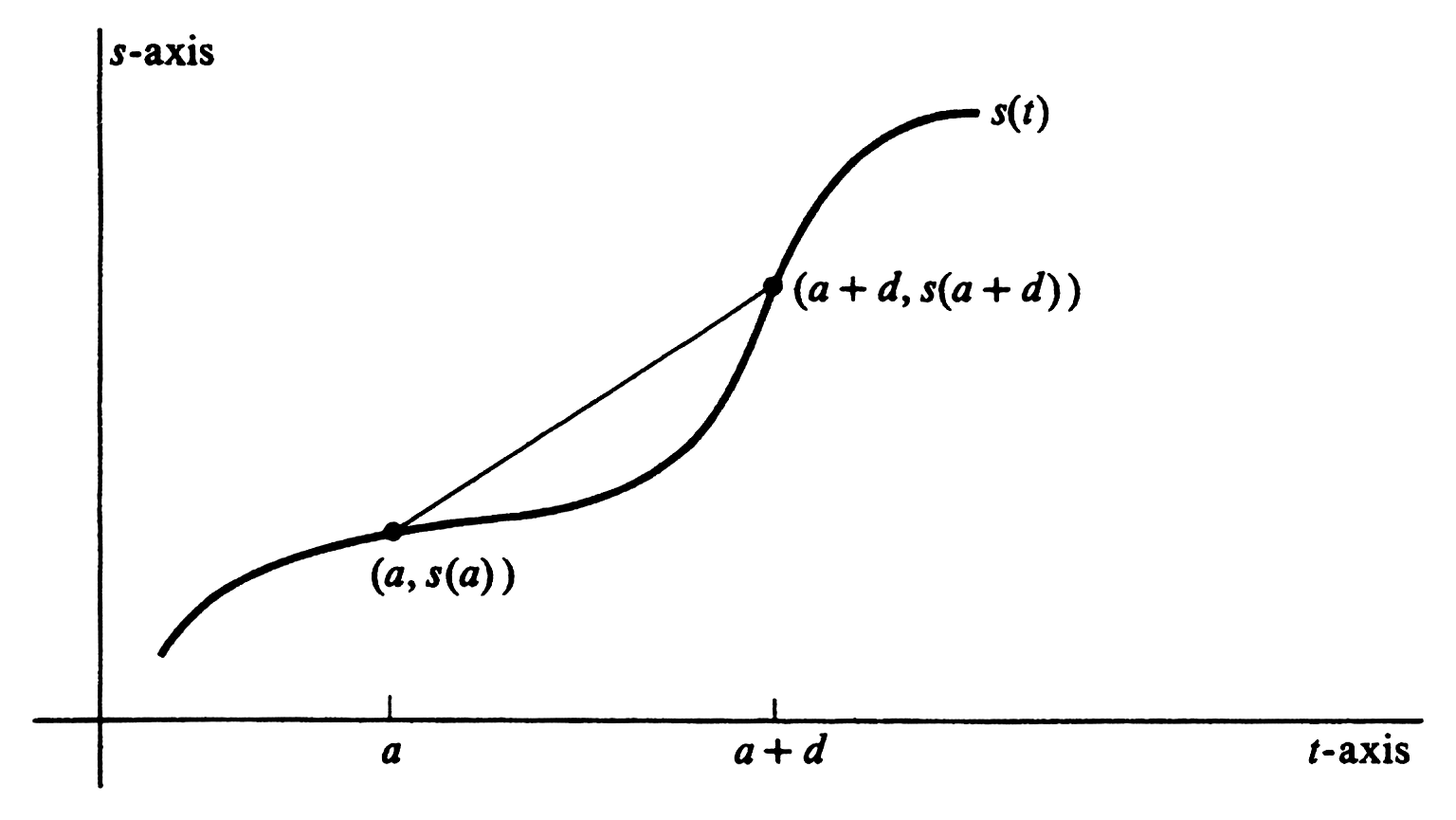

If we graph <math>s(t)</math> on a time-position graph, as in [[#fig 2.15|Figure]], we see that the average velocity is the slope of the line segment connecting the point <math>(a, s(a))</math> to the point <math>(a + d, s(a + d))</math>. If, keeping a fixed, we consider average velocities over successively shorter and shorter intervals of time, we obtain values nearer and nearer to the rate of change of <math>s</math> at <math>t = a</math>. We take this limit as d approaches zero as the definition of '''velocity''' at <math>a</math> and use the symbol <math>v(a)</math> for it. Thus | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

v(a) = \lim_{d \rightarrow 0} v_{av} = \lim_{d \rightarrow 0} \frac{s(a + d) - s(a)}{d} = s'(a). | |||

</math> | |||

Hence velocity is the derivative of position with respect to time, and we write <math>v(t) = s'(t)</math>, or simply <math>v = s'</math>. Geometrically, the velocity at a is the slope of the tangent line to the graph of the function <math>s</math> at the point <math>(a, s(a))</math>. | |||

For a particle moving on a real number line, a positive value of <math>v(t)</math> means that the motion at time <math>t</math> is in the direction of increasing numerical values, which is called the positive direction (i.e., if the line is the <math>x</math>-axis, then the particle is moving to the right). If <math>v(t)</math> is negative, then the particle is moving in the opposite direction. Finally, zero velocity indicates that the particle is at rest. The '''speed''' at time <math>t</math> is defined to be the absolute value <math>|v(t)|</math> of the velocity. Obviously, the speed measures how fast the particle is moving without regard to its direction. | |||

Velocity depends on time, and its rate of change with respect to time will tell us even more about the motion of a particle. This rate of change is called '''acceleration''' and is defined to be the derivative of velocity with respect to time. Denoted by <math>a</math>, it is the second derivative of position with respect to time: | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

a(t)= v'(t)= s''(t). | |||

</math> | |||

The acceleration is the rate of change of velocity with respect to time. It may be positive, indicating that the velocity is increasing; zero, telling us that the velocity is constant; or negative, indicating that the velocity is decreasing. For motion of a particle on a horizontal number line (or the <math>x</math>-axis) we have several possibilities. If the velocity is positive and the aceeleration is positive, the motion is to the right and the speed of the particle is increasing. If the velocity is positive and the aeeeleration is negative, the motion is still to the right but the particle is slowing down. If the acceleration is zero, the velocity is momentarily not changing. If the velocity is negative, the particle is moving to the left and it is slowing down or speeding up, depending on whether the acceleration is, respectively, positive or negative. | |||

\medskip | |||

'''Example''' | |||

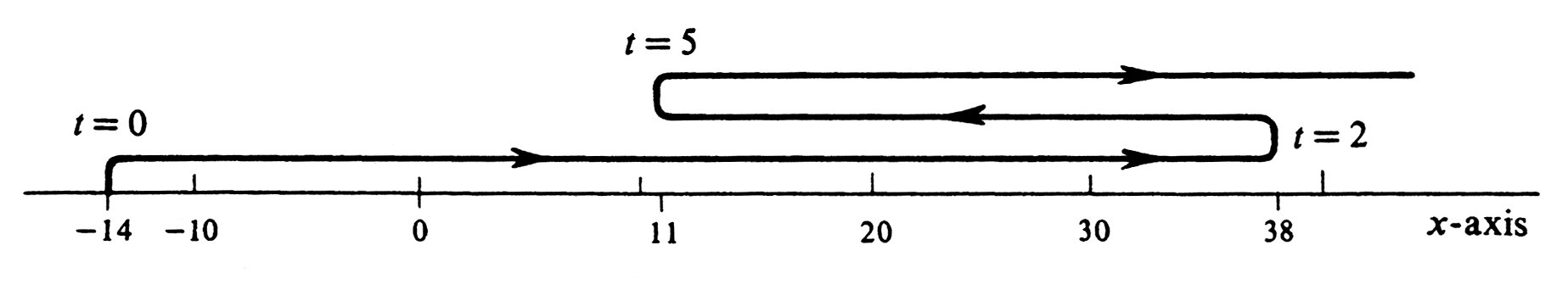

A particle moves on the <math>x</math>-axis and its coordinate, as a function of time, is given by <math>x(t) = 2t^3 - 21t^2 + 60t - 14</math>, where <math>t</math> is measured in seconds. Describe its motion. We first take derivatives to find velocity and acceleration: <math>v(t) = 6t^2 - 42t + 60 = 6(t^2 - 7t + 10) = 6(t - 2)(t - 5)</math> and <math>a(t) = 12t - 42 = 6(2t - 7)</math>. At zero time the particle is at <math>x = -14</math>, moving to the right with a velocity of 60 units per second. At that moment, acceleration is <math>-42</math>, and the particle is slowing down. At time <math>t = 2</math>, the particle is at rest <math>(v = 0)</math> at <math>x = 38</math>, and the acceleration is still negative: <math>a = -18</math>. For the next <math>1\frac{1}{2}</math> seconds the particle moves to the left until, at <math>t = \frac{7}{2}</math> it is at <math>x = 24\frac{1}{2}</math>, moving to the left with a speed of <math>13\frac{1}{2}</math> units per second. At that moment, however, the acceleration is zero and, in the next instant, the velocity will begin to increase to the right and the particle begin to slow down. The particle continues to move to the left for the next <math>1\frac{1}{2}</math> seconds, until <math>t = 5</math>. At that time, the particle is at rest at <math>x = 11</math> and the acceleration is positive. From that time on, the particle will move to the right with ever-increasing velocity. Its motion is indicated in [[#fig 2.16|Figure]]. | |||

\medskip | |||

<div id="fig 2.16" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig2_16.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

'''Example''' | |||

In a first course in physics, one encounters the formula for straight-line motion with constant acceleration, <math>s = s_0 + v_{0}t + \frac{1}{2} a{t^2}</math>, where <math>s</math> is the distance from some fixed point, <math>s_0</math> the initial distance, <math>v_0</math> the initial velocity, and a the acceleration. Find <math>v</math> and <math>a</math>, thereby verifying another formula which usually accompanies the distance formula and also verifying that the acceleration is constant. Taking derivatives with respect to time, we obtain <math>v = s' = v_0 + \frac{1}{2}a(2t) = v_0 + at</math> and <math>a = v' = a</math>. Thus we see that the derivative definitions do produce the familiar formulas. | |||

\medskip | |||

If a particle is constrained to move in the <math>xy</math>-plane on a circle of radius 5, then the point where it is at any time has coordinates which satisfy the equation <math>x^2 + y^2 = 25</math>. Each of the coordinates, however, is a function of time and we may write <math>[x(t)]^2 + [y(t)]^2 = 25</math>. Here we have an equation which states that two functions of <math>t</math>, <math>[x(t)]^2 + y(t)]^2</math> and the constant function 25, are equal to each other. If the two functions are equal, they will change with respect to <math>t</math> at the same rate. Taking derivatives to find the common rate of change, we have | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\frac{d}{dt} (x^2 + y^2 ) = \frac{d}{dt} 25, | |||

</math> | |||

which implies | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

2x \frac{dx}{dt} + 2y \frac{dy}{dt} = 0. | |||

</math> | |||

We interpret <math>\frac{dx}{dt}</math> as the rate of change of the abscissa of the particle with respect to time, or as the velocity in the horizontal direction. Similarly, we interpret <math>\frac{dy}{dt}</math> as the velocity in the vertical direction. We use the symbols <math>v = x</math> for <math>\frac{dx}{dt}</math> and <math>v_y</math> for <math>\frac{dy}{dt}</math>. Another interpretation of <math>v_x</math> and <math>v_y</math>, is that they are horizontal and vertical components, respectively, of the velocity of the particle. Using this notation, we write <math>xv_x + yv_y = 0</math> or <math>v_x = -\frac{y}{x}v_y</math>. These equations relate two rates of change, and problems of this type are called | |||

'''related rate''' problems. | |||

\medskip | |||

'''Example''' | |||

A particle moves on the circle with equation <math>x^2 + y^2 = 10</math>. As it passes through the point <math>(- 1, - 3)</math> the horizontal component of its velocity is 6 units per second. Find the vertical component. We first take derivatives with respect to time, <math>\frac{d}{dt}(x^2 + y^2) = \frac{d}{dt} 10</math>, to get <math>2xv_x + 2yv_y = 0</math>. | |||

We are given that <math>v_x = 6</math> when <math>x = -1</math> and <math>y = -3</math>. Substituting these values in the last equation, we have <math>2(-1)(6) + 2(-3)v_y = 0</math>. Hence <math>-12 - 6v_y = 0</math>, or <math>v_y = -2</math>. The vertical component of velocity is <math>-2</math> units per second, indicating that the motion is, at that moment, downward and to the right, since <math>v_x</math> is given positive. It is, of course, obvious that a particle which is constrained to move on the circle must be moving downward if it is moving to the right in the third quadrant. | |||

\medskip | |||

'''Example''' | |||

A spherical balloon is being blown up, and its volume is increasing at a rate of 4 cubic inches per second. At what rate is its radius increasing? The volume of a sphere is given by the equation, <math>V= \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3</math>. Since <math>V</math> and <math>\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3</math> are both functions of <math>t</math>, their derivatives with respect to <math>t</math> are equal. Thus <math>\frac{dV}{dt} = \frac{3}{4}\pi \cdot 3r^2 \frac{dr}{dt} = 4 \pi r^2 \frac{dr}{dt}.</math> Replacing <math>\frac{dV}{dt}</math> by 4 and solving for <math>\frac{dr}{dt}</math>, we have <math>\frac{dr}{dt} = \frac{1}{\pi r^2}</math>. The rate at which the radius is increasing is not constant, but depends on the radius at a particular moment. When the radius is 2 inches, it is increasing <math>\frac{1}{4 \pi}</math> inches per second; when it is 5 inches, it is increasing <math>\frac{1}{25 \pi}</math> inches per second, etc. | |||

\medskip | |||

Most related rate problems are solved by first finding an equation relating the variables. Then we may take derivatives to find an equation relating their rates of change with respect to time. Finally, we substitute those simultaneous values of the variables and rates which are given to us in the problem. | |||

\end{exercise} | |||

==General references== | |||

{{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | |||

Revision as of 01:07, 3 November 2024

Rates of Change with respect to Time.

The values of many physical quantities depend on time and change with time. In a mathematical formulation such a quantity is usually denoted by a variable which is a function of time. In this section we are concerned with the instantaneous rates of change of time-dependent variables. Let [math]u[/math] be a real-valued function of a real variable [math]t[/math], where we identify [math]t[/math] with time. The rate of change of [math]u[/math] with respect to time at a given instant [math]t = a[/math] can be determined by considering the derivative of [math]u[/math]. We have already observed in Chapter 1 that the derivative [math]f'(a)[/math] of a function [math]f[/math] at a particular number [math]a[/math] is the rate of change of the value [math]f(x)[/math] of the function [math]f[/math] with respect to [math]x[/math] at [math]a[/math]. It follows that the instantaneous rate of change of [math]u[/math] with respect to time, when [math]t = a[/math], is equal to the derivative:

In a physical application the variable [math]u[/math] might denote the number of gallons of water in a tank at time [math]t[/math], where [math]t[/math] is measured in minutes. Then, [math]\frac{d}{du}(a)[/math] is equal to the rate at which water is flowing in or out of the tank at time [math]t = a[/math] and is measured in gallons per minute. If [math]\frac{d}{du}(a)[/math] is positive, then the quantity of water in the tank is increasing when [math]t = a[/math] and water is flowing into the tank. On the other hand, if [math]\frac{d}{du}(a)[/math] is negative, then the amount of water is decreasing at that moment and water is draining out. Finally, if [math]\frac{d}{du}(a) = 0[/math], then the amount is not changing at [math]t = a[/math]. An important example of rate of change with respect to time is velocity. For example, consider a car in motion on a straight road. To formulate the situation mathematically, we identify the road with a real number line, the car with a point on the line, and the location of the car at time [math]t[/math] with the coordinate [math]s(t)[/math] of the point on the line. Thus, [math]s[/math] is a real-valued function of the real variable [math]t[/math]. The average velocity during the time interval from [math]t = a[/math] to [math]t = a + d[/math] is equal to the change in position divided by the change in time. Denoting this quantity by [math]v_{av}[/math], we have

If we graph [math]s(t)[/math] on a time-position graph, as in Figure, we see that the average velocity is the slope of the line segment connecting the point [math](a, s(a))[/math] to the point [math](a + d, s(a + d))[/math]. If, keeping a fixed, we consider average velocities over successively shorter and shorter intervals of time, we obtain values nearer and nearer to the rate of change of [math]s[/math] at [math]t = a[/math]. We take this limit as d approaches zero as the definition of velocity at [math]a[/math] and use the symbol [math]v(a)[/math] for it. Thus

Hence velocity is the derivative of position with respect to time, and we write [math]v(t) = s'(t)[/math], or simply [math]v = s'[/math]. Geometrically, the velocity at a is the slope of the tangent line to the graph of the function [math]s[/math] at the point [math](a, s(a))[/math]. For a particle moving on a real number line, a positive value of [math]v(t)[/math] means that the motion at time [math]t[/math] is in the direction of increasing numerical values, which is called the positive direction (i.e., if the line is the [math]x[/math]-axis, then the particle is moving to the right). If [math]v(t)[/math] is negative, then the particle is moving in the opposite direction. Finally, zero velocity indicates that the particle is at rest. The speed at time [math]t[/math] is defined to be the absolute value [math]|v(t)|[/math] of the velocity. Obviously, the speed measures how fast the particle is moving without regard to its direction. Velocity depends on time, and its rate of change with respect to time will tell us even more about the motion of a particle. This rate of change is called acceleration and is defined to be the derivative of velocity with respect to time. Denoted by [math]a[/math], it is the second derivative of position with respect to time:

The acceleration is the rate of change of velocity with respect to time. It may be positive, indicating that the velocity is increasing; zero, telling us that the velocity is constant; or negative, indicating that the velocity is decreasing. For motion of a particle on a horizontal number line (or the [math]x[/math]-axis) we have several possibilities. If the velocity is positive and the aceeleration is positive, the motion is to the right and the speed of the particle is increasing. If the velocity is positive and the aeeeleration is negative, the motion is still to the right but the particle is slowing down. If the acceleration is zero, the velocity is momentarily not changing. If the velocity is negative, the particle is moving to the left and it is slowing down or speeding up, depending on whether the acceleration is, respectively, positive or negative. \medskip Example

A particle moves on the [math]x[/math]-axis and its coordinate, as a function of time, is given by [math]x(t) = 2t^3 - 21t^2 + 60t - 14[/math], where [math]t[/math] is measured in seconds. Describe its motion. We first take derivatives to find velocity and acceleration: [math]v(t) = 6t^2 - 42t + 60 = 6(t^2 - 7t + 10) = 6(t - 2)(t - 5)[/math] and [math]a(t) = 12t - 42 = 6(2t - 7)[/math]. At zero time the particle is at [math]x = -14[/math], moving to the right with a velocity of 60 units per second. At that moment, acceleration is [math]-42[/math], and the particle is slowing down. At time [math]t = 2[/math], the particle is at rest [math](v = 0)[/math] at [math]x = 38[/math], and the acceleration is still negative: [math]a = -18[/math]. For the next [math]1\frac{1}{2}[/math] seconds the particle moves to the left until, at [math]t = \frac{7}{2}[/math] it is at [math]x = 24\frac{1}{2}[/math], moving to the left with a speed of [math]13\frac{1}{2}[/math] units per second. At that moment, however, the acceleration is zero and, in the next instant, the velocity will begin to increase to the right and the particle begin to slow down. The particle continues to move to the left for the next [math]1\frac{1}{2}[/math] seconds, until [math]t = 5[/math]. At that time, the particle is at rest at [math]x = 11[/math] and the acceleration is positive. From that time on, the particle will move to the right with ever-increasing velocity. Its motion is indicated in Figure. \medskip

Example

In a first course in physics, one encounters the formula for straight-line motion with constant acceleration, [math]s = s_0 + v_{0}t + \frac{1}{2} a{t^2}[/math], where [math]s[/math] is the distance from some fixed point, [math]s_0[/math] the initial distance, [math]v_0[/math] the initial velocity, and a the acceleration. Find [math]v[/math] and [math]a[/math], thereby verifying another formula which usually accompanies the distance formula and also verifying that the acceleration is constant. Taking derivatives with respect to time, we obtain [math]v = s' = v_0 + \frac{1}{2}a(2t) = v_0 + at[/math] and [math]a = v' = a[/math]. Thus we see that the derivative definitions do produce the familiar formulas. \medskip If a particle is constrained to move in the [math]xy[/math]-plane on a circle of radius 5, then the point where it is at any time has coordinates which satisfy the equation [math]x^2 + y^2 = 25[/math]. Each of the coordinates, however, is a function of time and we may write [math][x(t)]^2 + [y(t)]^2 = 25[/math]. Here we have an equation which states that two functions of [math]t[/math], [math][x(t)]^2 + y(t)]^2[/math] and the constant function 25, are equal to each other. If the two functions are equal, they will change with respect to [math]t[/math] at the same rate. Taking derivatives to find the common rate of change, we have

which implies

We interpret [math]\frac{dx}{dt}[/math] as the rate of change of the abscissa of the particle with respect to time, or as the velocity in the horizontal direction. Similarly, we interpret [math]\frac{dy}{dt}[/math] as the velocity in the vertical direction. We use the symbols [math]v = x[/math] for [math]\frac{dx}{dt}[/math] and [math]v_y[/math] for [math]\frac{dy}{dt}[/math]. Another interpretation of [math]v_x[/math] and [math]v_y[/math], is that they are horizontal and vertical components, respectively, of the velocity of the particle. Using this notation, we write [math]xv_x + yv_y = 0[/math] or [math]v_x = -\frac{y}{x}v_y[/math]. These equations relate two rates of change, and problems of this type are called related rate problems. \medskip Example

A particle moves on the circle with equation [math]x^2 + y^2 = 10[/math]. As it passes through the point [math](- 1, - 3)[/math] the horizontal component of its velocity is 6 units per second. Find the vertical component. We first take derivatives with respect to time, [math]\frac{d}{dt}(x^2 + y^2) = \frac{d}{dt} 10[/math], to get [math]2xv_x + 2yv_y = 0[/math]. We are given that [math]v_x = 6[/math] when [math]x = -1[/math] and [math]y = -3[/math]. Substituting these values in the last equation, we have [math]2(-1)(6) + 2(-3)v_y = 0[/math]. Hence [math]-12 - 6v_y = 0[/math], or [math]v_y = -2[/math]. The vertical component of velocity is [math]-2[/math] units per second, indicating that the motion is, at that moment, downward and to the right, since [math]v_x[/math] is given positive. It is, of course, obvious that a particle which is constrained to move on the circle must be moving downward if it is moving to the right in the third quadrant. \medskip Example

A spherical balloon is being blown up, and its volume is increasing at a rate of 4 cubic inches per second. At what rate is its radius increasing? The volume of a sphere is given by the equation, [math]V= \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3[/math]. Since [math]V[/math] and [math]\frac{4}{3}\pi r^3[/math] are both functions of [math]t[/math], their derivatives with respect to [math]t[/math] are equal. Thus [math]\frac{dV}{dt} = \frac{3}{4}\pi \cdot 3r^2 \frac{dr}{dt} = 4 \pi r^2 \frac{dr}{dt}.[/math] Replacing [math]\frac{dV}{dt}[/math] by 4 and solving for [math]\frac{dr}{dt}[/math], we have [math]\frac{dr}{dt} = \frac{1}{\pi r^2}[/math]. The rate at which the radius is increasing is not constant, but depends on the radius at a particular moment. When the radius is 2 inches, it is increasing [math]\frac{1}{4 \pi}[/math] inches per second; when it is 5 inches, it is increasing [math]\frac{1}{25 \pi}[/math] inches per second, etc. \medskip Most related rate problems are solved by first finding an equation relating the variables. Then we may take derivatives to find an equation relating their rates of change with respect to time. Finally, we substitute those simultaneous values of the variables and rates which are given to us in the problem.

\end{exercise}

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.