guide:73a0142ed5: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="d-none"><math> | |||

\newcommand{\ex}[1]{\item } | |||

\newcommand{\sx}{\item} | |||

\newcommand{\x}{\sx} | |||

\newcommand{\sxlab}[1]{} | |||

\newcommand{\xlab}{\sxlab} | |||

\newcommand{\prov}[1] {\quad #1} | |||

\newcommand{\provx}[1] {\quad \mbox{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\intext}[1]{\quad \mbox{#1} \quad} | |||

\newcommand{\R}{\mathrm{\bf R}} | |||

\newcommand{\Q}{\mathrm{\bf Q}} | |||

\newcommand{\Z}{\mathrm{\bf Z}} | |||

\newcommand{\C}{\mathrm{\bf C}} | |||

\newcommand{\dt}{\textbf} | |||

\newcommand{\goesto}{\rightarrow} | |||

\newcommand{\ddxof}[1]{\frac{d #1}{d x}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddx}{\frac{d}{dx}} | |||

\newcommand{\ddt}{\frac{d}{dt}} | |||

\newcommand{\dydx}{\ddxof y} | |||

\newcommand{\nxder}[3]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{d{#3}^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\deriv}[2]{\frac{d^{#1}{#2}}{dx^{#1}}} | |||

\newcommand{\dist}{\mathrm{distance}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccot}{\mathrm{arccot\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccsc}{\mathrm{arccsc\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsec}{\mathrm{arcsec\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arctanh}{\mathrm{arctanh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arcsinh}{\mathrm{arcsinh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\arccosh}{\mathrm{arccosh\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\sech}{\mathrm{sech\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\csch}{\mathrm{csch\:}} | |||

\newcommand{\conj}[1]{\overline{#1}} | |||

\newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb} | |||

</math></div> | |||

===Complex Numbers.=== | |||

Since the square of a real number is never negative, the equation <math>x^2 = -1</math> has no solution in the set <math>R</math> of all real numbers. However, we shall show that <math>R</math> can be considered as a subset of a larger set <math>C</math> which has the following properties: | |||

(i) The sum and product of any two elements in <math>C</math> are defined, and addition and multiplication obey the ordinary laws of algebra. (ii) There is an element <math>i</math> in <math>C</math> such that <math>i^2 = - 1</math>. (iii) Every element in <math>C</math> can be written in the form <math>x + iy</math>, where <math>x</math> and <math>y</math> are real numbers. The elements of the set <math>C</math> are called '''complex numbers'''. Let us assume, for the moment, that the existence of <math>C</math>, obeying the three properties, has already been demonstrated. Then the sum of two complex numbers <math>x_{1} + iy_1</math> and <math>x_{2} + iy_2</math> is given by | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq6.6.1"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

(x_{1} + iy_{1}) + (x_{2} + iy_{2}) = (x_{1} + x_{2}) + i(y_{1} + y_{2}). | |||

\label{eq6.6.1} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

For the product, we have | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

(x_{1} + iy_{1})(x_{2} + iy_{2}) &=& x_{1}x_{2} + iy_{1}x_{2} + iy_{2}x_{1} + i^{2}y_{1}y_{2} \\ | |||

&=& x_{1}x_{2} + i(x_{1}y_{2} + x_{2}y_{1}) + i^{2}y_{1}y_{2}. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

However, since <math>i^2 = -1</math>, we get | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq6.6.2"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

(x_{1} + iy_{1})(x_{2} + iy_{2}) = (x_{1}x_{2} - y_{1}y_{2}) + i(x_{1}y_{2} + x_{2}y_{1}). | |||

\label{eq6.6.2} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

For example, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

(2 + i) + (5 - i3) &=& 7 - i2, \\ | |||

(2 + i)(5 - i3) &=& 10 + i5 - i6 - i^{2}3 \\ | |||

&=& 10 - i - (-1)3\\ | |||

&=& 13 - i. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

We turn now to the task of showing that there is a set <math>C</math> having the properties listed in (i), (ii), and (iii). We shall take for <math>C</math> the set <math>R^2</math> of all ordered pairs of real numbers, i.e., the <math>xy</math>-plane. Thus a complex number is by definition an ordered pair <math>(x, y)</math> of real numbers. Up to this point we have not ascribed any algebraic structure to the <math>xy</math>-plane, and so we must define what we mean by addition and multiplication of ordered pairs of real numbers. Later in this section we shall show how to express the ordered pair <math>(x, y)</math> in the traditional form <math>x + iy</math>. Anticipating this, however, we use equations (1) and (2) to motivate the definitions of the sum and product of ordered pairs. We define | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq6.6.3"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

(x_{1}, y_{1}) + (x_{2}, y_{2}) = (x_{1} + x_{2}, y_{1} + y_{2}), | |||

\label{eq6.6.3} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

<span id{{=}}"eq6.6.4"/> | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{equation} | |||

(x_{1}, y_{1})(x_{2}, y_{2}) = (x_{1}x_{2} - y_{1}y_{2}, x_{1}y_{2} + x_{2}y_{1}). | |||

\label{eq6.6.4} | |||

\end{equation} | |||

</math> | |||

It was stated that addition and multiplication of complex numbers are to obey the ordinary laws | |||

of algebra. By this we mean that the following six propositions are true. The basic algebraic | |||

properties which they describe | |||

are the same as those for the real numbers, and these six statements should be compared with | |||

the corresponding list on page 2. Abbreviating <math>(x_{1}, y_{1}), (x_{2}, y_{2})</math>, and <math>(x_{3}, y_{3})</math> by <math>z_{1}, z_{2}</math>, and <math>z_{3}</math>, respectively, we have | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-1|'''ASSOCIATIVE LAWS.''' | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

z_{1} + (z_{2} + z_{3}) = (z_{1} + z_{2}) + z_{3},\;\;\; z_1(z_{2}z_{3}) = (z_{1}z_{2})z_{3}. | |||

</math>|}} | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-2|'''COMMUTATIVE LAWS.''' | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

z_{1} + z_{2} = z_{2} + z_{1},\;\;\; z_{1}z_{2} = z_{2}z_{1}. | |||

</math>|}} | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-3|'''DISTRIBUTIVE LAW.''' | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

(z_1 + z_2)z_3 = z_{1}z_{3} + z_{2}z_{3}. | |||

</math>|}} | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-4|'''EXISTENCE OF IDENTITIES.''' | |||

The two complex numbers <math>0' = (0, 0)</math> and <math>1' = (1, 0)</math> have the properties that <math>0' + z = z</math> | |||

and <math>1'z = z</math> for every <math>z</math> in <math>C</math>.|}} | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-5|'''EXISTENCE OF SUBTRACTION.''' | |||

For every complex number <math>z = (x, y)</math>, the complex number <math>(-x, -y)</math> is denoted by <math>-z</math> and has the property that <math>z + (-z) = 0'</math>. [The expression <math>z_1 - z_2</math> is an abbreviation for <math>z_{1} + (-z_{2}).</math>]|}} | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-6|'''EXISTENCE OF DIVISION.''' | |||

For every complex number <math>z = (x, y)</math> different from <math>0'</math>, the complex number <math>\Bigl(\frac{x}{x^2 + y^2}, \frac{-y}{x^2 + y^2}\Bigr)</math> is denoted by <math>z^{-1}</math> or <math>\frac{1}{z}</math> and has the property that <math>zz^{-1} = 1'</math>. <math>\Bigl(</math> The expression <math>\frac{z_1}{z_2}</math> is an abbreviation for | |||

<math>z_{1}z_{2}^{-1}</math>. <math>\Bigr)</math> | |||

|The proofs are simple exercises using the definitions and the algebraic properties of real | |||

numbers. We give the proofs of (6.4) and (6.6) and leave the others for the reader to supply. It | |||

is asserted in (6.4) that the complex number (0, 0), which is abbreviated <math>0'</math> (and later simply | |||

as 0), is an additive identity. Letting <math>z = (x, y)</math>, we have | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

0'+ z = (0,0) + (x, y) = (0 + x, 0 + y) = (x, y) = z, | |||

</math> | |||

which proves the assertion. Similarly, for the multiplicative identity <math>1' = (1, 0)</math> (later to be | |||

abbreviated simply by 1), we obtain | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

1'z = (1, 0)(x, y) = (1x - 0y, 1y + x0) = (x, y) = z, | |||

</math> | |||

and the proof of (6.4) is complete. | |||

To prove (6.6), let <math>z= (x,y)</math> be a complex number different from <math>0' = (0, 0)</math>. It follows that <math>x^2 | |||

+ y^2</math> is positive. Hence the ordered pair <math>\Bigl(\frac{x}{x^2 + y^2}, \frac{-y}{x^2 + y^2}\Bigr)</math> is defined, and (in anticipation of the proof) is denoted <math>z^{-1}</math>. Multiplying, we get | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

zz^{-1} &=& (x, y) \Bigl(\frac{x}{x^2 + y^2}, \frac{-y}{ x^2 + y^2} \Bigr)\\ | |||

&=& \Bigl(\frac{x^2}{x^2 + y^2} - \frac{-y^2}{ x^2 + y^2}, \frac{-xy}{x^2 + y^2} + \frac{xy}{x^2 + y^2}\Bigr)\\ | |||

&=& \Bigl(\frac{x^2 + y^2}{x^2 + y^2}, 0\Bigr) = (1,0)\\ | |||

&=& 1', | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

which completes the proof of (6.6).}} | |||

Assuming that the remaining four propositions have been proved, we have now satisfied requirement (i) in the first paragraph of the section for the set <math>C</math> of complex numbers: | |||

Addition and multiplication are defined and obey the ordinary laws of algebra. But what about the prior assumption that the set <math>R</math> of all real numbers can be considered a subset of <math>C</math>? | |||

Of course, it is not actually a subset, since no real number is also an ordered pair of real numbers. However, there is a subset of <math>C</math> which has all the properties of <math>R</math>. This subset is the <math>x</math>-axis, the set of all complex numbers whose second coordinate is zero. Speaking informally, we shall identify <math>R</math> with the <math>x</math>-axis in <math>C</math> by identifying an arbitrary real number <math>x</math> with the complex number <math>(x, 0)</math>. Proceeding formally, we define a function whose value for each real number <math>x</math> is denoted by <math>x'</math> and defined by <math>x' = (x, 0)</math>. This function sets up a one-to-one correspondence between the set <math>R</math> and the <math>x</math>-axis in <math>C</math>. Essential, however, is the fact that this correspondence preserves the algebraic operations of addition and multiplication. To show that this is so, let <math>x_{1}</math> and <math>x_{2}</math> be any two real numbers. Then, for addition, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

x'_{1} + x'_{2} = (x_{1}, 0) + (x_{2}, 0) = (x_{1} + x_{2}, 0) = (x_{1} + x_{2})', | |||

</math> | |||

and for multiplication, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

x'_{1}x'_{2} = (x_{1}, 0)(x_{2}, 0) &=& (x_{1}x_{2} - 0 \cdot 0, x_{1} \cdot 0 + x_{2} \cdot 0)\\ | |||

&=& (x_{1}x_{2}, 0) = (x_{1}x_{2})'. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

It follows that the algebraic properties of the set <math>R</math> of all real numbers are identical with those of the <math>x</math>-axis in <math>C</math>. It is therefore legitimate to make the identification, and henceforth we shall denote <math>x'</math> simply by <math>x</math>. Note that in so doing, the additive identity <math>0'</math> and the multiplicative identity <math>1'</math>, referred to in (6.4), become simply 0 and 1, respectively. | |||

We now define <math>i</math> to be the complex number (0, 1). Requirement (ii) in the first paragraph of | |||

this section is easily seen to be satisfied: | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

i^2 = (0, 1)(0, 1) &=& (0 \cdot 0 - 1 \cdot 1, 0 \cdot 1 + 0 \cdot 1)\\ | |||

&=& (-1,0) = - (1,0). | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

Since we have agreed to write <math>(1, 0) = 1' = 1</math>, we therefore obtain the famous equation | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-7| | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

i^2 = -1. | |||

</math>|}} | |||

Requirement (iii) is | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-8|If <math>z = (x, y)</math> is an arbitrary complex number, then <math>z = x + iy</math>. | |||

|The expression <math>x + iy</math> is an abbreviation for the more formal <math>x' + iy'</math>. Hence | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

x + iy &=& (x, 0) + (0, 1)(y, 0) \\ | |||

&=& (x, 0)+ (0 \cdot y - 1 \cdot 0, 0 \cdot 0 + y \cdot 1) \\ | |||

&=& (x, 0) + (0, y) = (x, y) \\ | |||

&=& z, | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

completing the proof, and also our construction of the set <math>C</math> of complex numbers.}} | |||

'''Example''' | |||

If <math>z_{1} = 4 + i3, z_{2} = 4 - i3</math>, and <math>z_{3} = 7 - i2</math>, then find <math>z_{1} + z_{2}, z_{1}z_{2}, 3z_{1} - 2z_{3}</math>, and <math>z_{1}z_{3}</math>. These are simply routine exercises involving the addition, subtraction, and multiplication of complex numbers. | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

z_{1} + z_{2} &=& (4 + i3) + (4 - i3) = 8, \\ | |||

z_{1}z_{2} &=& (4 + i3)(4 - i3) = 16 + i 12 - i 12 - i^{2}9 \\ | |||

&=& 16 - (-1) 9 = 25, \\ | |||

3z_{1} - 2z_{3} &=& 3(4 + i3) - 2(7 - i2) \\ | |||

&=& 12 + i9 - 14 + i4 = -2 + i13, \\ | |||

z_{1}z_{3} &=& (4 + i3)(7 - i2) = 28 + i21 - i8 - i^{2}6\\ | |||

&=& 28 - (-1)6 + i 13 = 34 + i 13. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

'''Example''' | |||

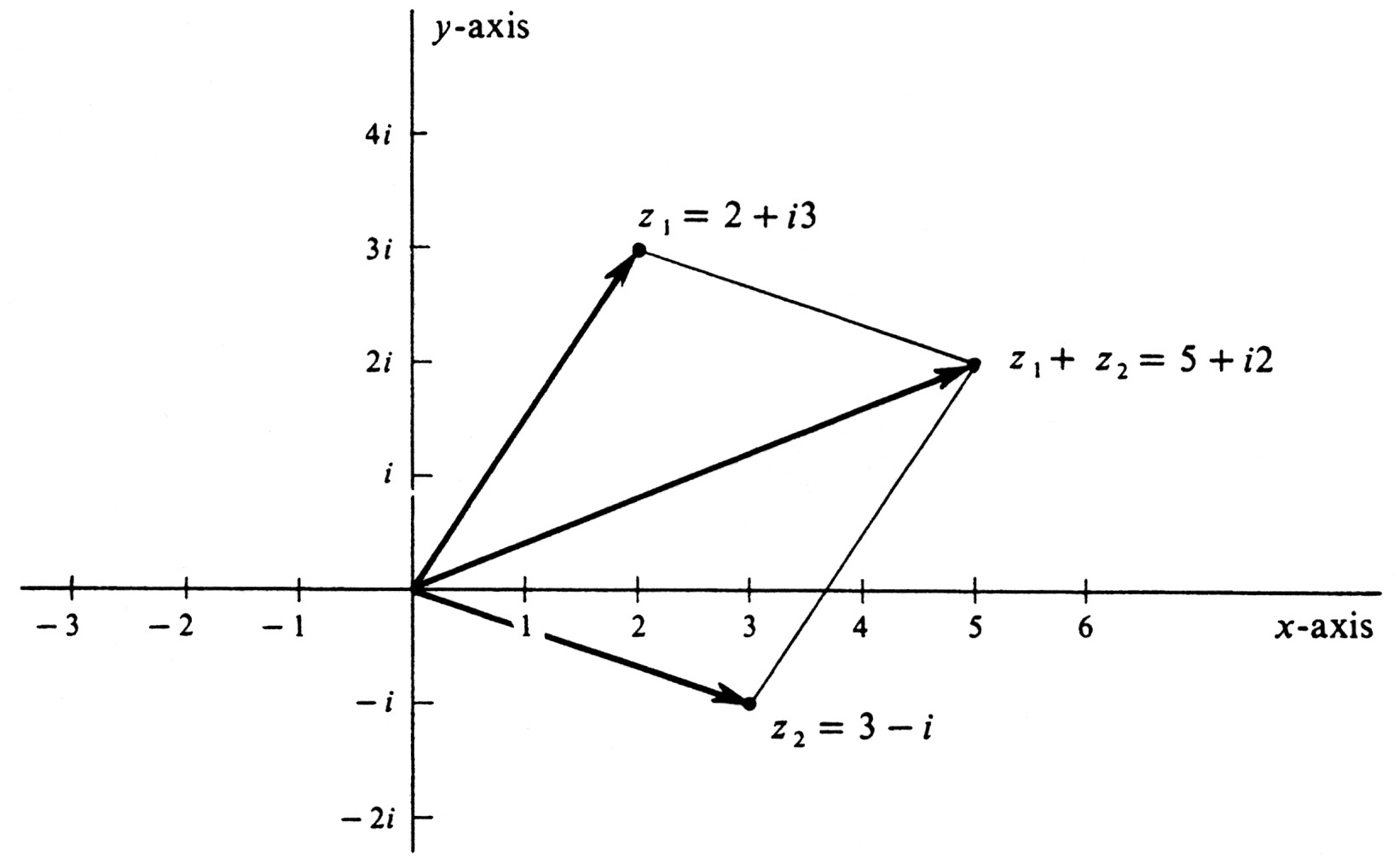

If <math>z_{1} = 2 + i3</math> and <math>z_{2} = 3 - i</math>, plot <math>z_{1}, z_{2}</math>, and <math>z_{1} + z_{2}</math> on the complex plane. We have | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

z_{1} + z_{2} = (2+ i3) + (3 - i) = 5 + i2, | |||

</math> | |||

and the three points are shown in Figure 19. | |||

<div id="fig 6.19" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | |||

[[File:guide_c5467_scanfig6_19.png | 400px | thumb | ]] | |||

</div> | |||

A complex number is a point in the <math>xy</math>-plane and can be indicated in a picture by a dot. Another useful geometric representation of <math>z</math> is an arrow with its tail at the origin and its head at the point <math>z</math>. We have drawn these arrows in Figure 19. Note that ''if $P$ is the parallelogram whose adjacent sides are the arrows representing $z_1$ and $z_2$, then the diagonal of $P$ which has the origin as an endpoint is the arrow representing the sum $z_{1} + z_{2}$.'' The definition of addition in <math>C</math> implies that this parallelogram principle is valid for every pair of complex numbers. | |||

It provides a good method for adding complex numbers geometrically. | |||

When the complex number <math>i</math> was first introduced in mathematics, it was regarded as highly mysterious and was called an '''imaginary number''', and this terminology has survived. If <math>z = x + iy</math> is an arbitrary complex number, then by definition <math>x</math> is the '''real part''' of <math>z</math>, and <math>y</math> is the '''imaginary part''' of <math>z</math>. Note that the imaginary part of a complex number is a real number. A complex number whose real part is zero, i.e., one that lies on the <math>y</math>-axis, is called '''pure imaginary.''' It is important to remember that | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-9|Two complex numbers are equal if and only if their real parts are equal and their imaginary parts are equal. That is, <math>x_{1} + iy_{1} = x_{2} + iy_{2}</math> if and only if <math>x_{1} = x_{2}</math> and <math>y_{1} = y_{2}</math>. | |||

|We know that <math>x_{1} + iy_{1} = (x_{1}, y_{1})</math> and <math>x_{2} + iy_{2} = (x_{2}, y_{2})</math>. But two ordered pairs are equal if and only if their first coordinates are equal and their second coordinates are equal, and so (6.9) is proved. Another proof, which uses only the algebraic properties of complex numbers rather than their explicit construction as ordered pairs, is the following. Suppose that <math>x_{1} + iy_{1} = x_{2} + iy_{2}</math>. Then <math>x_{1} - x_{2} = i(y_{2} - y_{1})</math>, and squaring both sides we obtain | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

(x_{1} - x_{2})^2 = i^{2}(y_{2} - y_{1})^2 = - (y_{2} - y_{1})^2. | |||

</math> | |||

The left side is a nonnegative real number, and the right side is a nonpositive real number. | |||

They can be equal only if both are zero. Hence <math>x_{1} = x_{2}</math> and <math>y_{2} = y_{1}</math>. | |||

The converse proposition is, of course, trivial.}} | |||

The '''absolute value,''' or '''modulus,''' of a complex number <math>z = x + iy</math> is a nonnegative real number denoted by <math>|z|</math> and defined by | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

|z| = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}. | |||

</math> | |||

The geometric significance of <math>|z|</math> is that it is the distance between the point <math>z</math> and the origin | |||

in the complex plane. If <math>z</math> is represented by an arrow, then <math>|z|</math> is the length of the arrow. | |||

Note that if <math>z</math> is real, i.e., if its imaginary part is equal to zero, then the absolute value of <math>z</math> | |||

is simply its absolute value as a real number. Thus, if <math>z = x + iy</math> and <math>y = 0</math>, then | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

|z| = \sqrt{x^2+ 0^2} = \sqrt{x^2} = |x|. | |||

</math> | |||

An important property of the absolute value is the following. | |||

{{proofcard|Theorem|theorem-10|The absolute value of the product of two complex numbers is the product of their absolute values; i.e., <math>|z_{1}z_{2}| = |z_{1}| |z_{2}|</math>. | |||

|Let <math>z_{1} = x_{1} + iy_{1}</math> and <math>z_{2} = x_{2} + iy_{2}</math>. Then we have | |||

<math>z_{1}z_{2} = x_{1}x_{2} - y_{1}y_{2} + i(x_{1}y_{2} + x_{2}y_{1})</math>. | |||

Hence, by the definition of absolute value, | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

|z_{1}z_{2}|^{2} = (x_{1}x_{2} - y_{1}y_{2})^2 + (x_{1}y_{2} + x_{2}y_{1})^2. | |||

</math> | |||

Simplifying, we get | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

|z_{1}z_{2}|^2 &=& x_{1}^{2} x_{2}^{2} - 2x_{1}x_{2}y_{1}y_{2} + y_{1}^{2}y_{2}^{2} | |||

+ x_{1}^{2}y_{2}^{2} + 2x_{1}x_{2}y_{1}y_{2} + x_{2}^{2}y_{1}^{2} \\ | |||

&=& x_{1}^{2}(x_{2}^{2} + y_{2}^{2}) + y_{1}^{2}(x_{2}^{2} + y_{2}^{2})\\ | |||

&=& (x_{1}^{2} + y_{1}^{2})(x_{2}^{2} + y_{2}^{2})\\ | |||

&=& |z_{1}|^{2} |z_{2}|^{2}. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

Thus <math>|z_{1}z_{2}| = |z_{1}|^{2} |z_{2}|^{2}</math>, and the proof is completed by taking | |||

the positive square root of each side of the equation.}} | |||

As an illustration of Theorem (6.10), consider the complex numbers and <math>z_{2}</math> shown | |||

in Figure 19. The product <math>z_{1}z_{2}</math> is equal to | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

z_{1}z_{2} = (2 + i3)(3 - i) &=& 6 + i9 - i2 - i^{2} 3\\ | |||

&=& 9 + i7. | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

The absolute values are | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\begin{eqnarray*} | |||

|z_{1}| &=& \sqrt{2^{2} + 3^{2}} = \sqrt{13}, \\ | |||

|z_{2}| &=& \sqrt{3^{2} + (- 1)^{2}} = \sqrt{10},\\ | |||

|z_{1}z_{2}| &=& \sqrt{9^2 + 7^{2}} = \sqrt{130}, | |||

\end{eqnarray*} | |||

</math> | |||

which is in agreement with (6.10). | |||

If <math>z = x + iy</math>, then the '''complex conjugate''' of <math>z</math>, denoted by \={z}, | |||

is defined to be the complex number | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\mbox{\={z}}\; = x- iy. | |||

</math> | |||

The product of a complex number and its complex conjugate is always a nonnegative real | |||

number, since | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

z \mbox{\={z}}\; = (x + iy)(x - iy) = x^2 + y^2. | |||

</math> | |||

Since <math>x^2 + y^2 = |z|^2</math>, we obtain the formula | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

z \mbox{\={z}}\; = |z|^2. | |||

</math> | |||

The complex conjugate is a useful tool for computing the real and imaginary parts of the | |||

quotient of two complex numbers. If <math>z_{1}</math> and <math>z_{2}</math> are given and if <math>z_{2} \neq 0</math>, | |||

then | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\frac{z_1}{z_2} = \frac{z_1}{z_2} \frac{\mbox{ \={z}}_2}{\mbox{ \={z}}_2} | |||

= \frac{z_{1}\mbox{ \={z}}_2}{| z_{2} |^2} | |||

</math> | |||

and the denominator of the right side is a real number. | |||

'''Example''' | |||

Compute the real and imaginary parts of the complex number <math>7 + i2</math>. The complex conjugate | |||

of <math>7 - i2</math> is the number <math>7 + i2</math>. Hence | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\frac{5 + i3}{7 - i2} = \frac{ 5 + i3}{ 7 - i2} \frac{7 + i2}{7+i2} = \frac{(5 + i3)(7 + i2)}{7^{2} +2^{2}}. | |||

</math> | |||

Since <math>(5 + i3)(7 + i2) = 35 - 6 + i21 + i 10 = 29 + i31</math>, we obtain | |||

<math display="block"> | |||

\frac{5 + i3}{7 - i2} = \frac{ 29 + i31}{ 53} = \frac{29}{53} + i \frac{31}{53}. | |||

</math> | |||

Thus the real part is <math>\frac{29}{53}</math>, and the imaginary part is <math>\frac{31}{53}</math>. | |||

\end{exercise} | |||

==General references== | |||

{{cite web |title=Crowell and Slesnick’s Calculus with Analytic Geometry|url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~doyle/docs/calc/calc.pdf |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2008 |access-date=Oct 29, 2024}} | |||

Revision as of 01:08, 3 November 2024

Complex Numbers.

Since the square of a real number is never negative, the equation [math]x^2 = -1[/math] has no solution in the set [math]R[/math] of all real numbers. However, we shall show that [math]R[/math] can be considered as a subset of a larger set [math]C[/math] which has the following properties: (i) The sum and product of any two elements in [math]C[/math] are defined, and addition and multiplication obey the ordinary laws of algebra. (ii) There is an element [math]i[/math] in [math]C[/math] such that [math]i^2 = - 1[/math]. (iii) Every element in [math]C[/math] can be written in the form [math]x + iy[/math], where [math]x[/math] and [math]y[/math] are real numbers. The elements of the set [math]C[/math] are called complex numbers. Let us assume, for the moment, that the existence of [math]C[/math], obeying the three properties, has already been demonstrated. Then the sum of two complex numbers [math]x_{1} + iy_1[/math] and [math]x_{2} + iy_2[/math] is given by

For the product, we have

However, since [math]i^2 = -1[/math], we get

For example,

We turn now to the task of showing that there is a set [math]C[/math] having the properties listed in (i), (ii), and (iii). We shall take for [math]C[/math] the set [math]R^2[/math] of all ordered pairs of real numbers, i.e., the [math]xy[/math]-plane. Thus a complex number is by definition an ordered pair [math](x, y)[/math] of real numbers. Up to this point we have not ascribed any algebraic structure to the [math]xy[/math]-plane, and so we must define what we mean by addition and multiplication of ordered pairs of real numbers. Later in this section we shall show how to express the ordered pair [math](x, y)[/math] in the traditional form [math]x + iy[/math]. Anticipating this, however, we use equations (1) and (2) to motivate the definitions of the sum and product of ordered pairs. We define

It was stated that addition and multiplication of complex numbers are to obey the ordinary laws

of algebra. By this we mean that the following six propositions are true. The basic algebraic

properties which they describe

are the same as those for the real numbers, and these six statements should be compared with

the corresponding list on page 2. Abbreviating [math](x_{1}, y_{1}), (x_{2}, y_{2})[/math], and [math](x_{3}, y_{3})[/math] by [math]z_{1}, z_{2}[/math], and [math]z_{3}[/math], respectively, we have

ASSOCIATIVE LAWS.

COMMUTATIVE LAWS.

DISTRIBUTIVE LAW.

EXISTENCE OF IDENTITIES. The two complex numbers [math]0' = (0, 0)[/math] and [math]1' = (1, 0)[/math] have the properties that [math]0' + z = z[/math] and [math]1'z = z[/math] for every [math]z[/math] in [math]C[/math].

EXISTENCE OF SUBTRACTION. For every complex number [math]z = (x, y)[/math], the complex number [math](-x, -y)[/math] is denoted by [math]-z[/math] and has the property that [math]z + (-z) = 0'[/math]. [The expression [math]z_1 - z_2[/math] is an abbreviation for [math]z_{1} + (-z_{2}).[/math]]

EXISTENCE OF DIVISION. For every complex number [math]z = (x, y)[/math] different from [math]0'[/math], the complex number [math]\Bigl(\frac{x}{x^2 + y^2}, \frac{-y}{x^2 + y^2}\Bigr)[/math] is denoted by [math]z^{-1}[/math] or [math]\frac{1}{z}[/math] and has the property that [math]zz^{-1} = 1'[/math]. [math]\Bigl([/math] The expression [math]\frac{z_1}{z_2}[/math] is an abbreviation for [math]z_{1}z_{2}^{-1}[/math]. [math]\Bigr)[/math]

The proofs are simple exercises using the definitions and the algebraic properties of real numbers. We give the proofs of (6.4) and (6.6) and leave the others for the reader to supply. It is asserted in (6.4) that the complex number (0, 0), which is abbreviated [math]0'[/math] (and later simply as 0), is an additive identity. Letting [math]z = (x, y)[/math], we have

Assuming that the remaining four propositions have been proved, we have now satisfied requirement (i) in the first paragraph of the section for the set [math]C[/math] of complex numbers: Addition and multiplication are defined and obey the ordinary laws of algebra. But what about the prior assumption that the set [math]R[/math] of all real numbers can be considered a subset of [math]C[/math]? Of course, it is not actually a subset, since no real number is also an ordered pair of real numbers. However, there is a subset of [math]C[/math] which has all the properties of [math]R[/math]. This subset is the [math]x[/math]-axis, the set of all complex numbers whose second coordinate is zero. Speaking informally, we shall identify [math]R[/math] with the [math]x[/math]-axis in [math]C[/math] by identifying an arbitrary real number [math]x[/math] with the complex number [math](x, 0)[/math]. Proceeding formally, we define a function whose value for each real number [math]x[/math] is denoted by [math]x'[/math] and defined by [math]x' = (x, 0)[/math]. This function sets up a one-to-one correspondence between the set [math]R[/math] and the [math]x[/math]-axis in [math]C[/math]. Essential, however, is the fact that this correspondence preserves the algebraic operations of addition and multiplication. To show that this is so, let [math]x_{1}[/math] and [math]x_{2}[/math] be any two real numbers. Then, for addition,

and for multiplication,

It follows that the algebraic properties of the set [math]R[/math] of all real numbers are identical with those of the [math]x[/math]-axis in [math]C[/math]. It is therefore legitimate to make the identification, and henceforth we shall denote [math]x'[/math] simply by [math]x[/math]. Note that in so doing, the additive identity [math]0'[/math] and the multiplicative identity [math]1'[/math], referred to in (6.4), become simply 0 and 1, respectively.

We now define [math]i[/math] to be the complex number (0, 1). Requirement (ii) in the first paragraph of

this section is easily seen to be satisfied:

Since we have agreed to write [math](1, 0) = 1' = 1[/math], we therefore obtain the famous equation

Requirement (iii) is

If [math]z = (x, y)[/math] is an arbitrary complex number, then [math]z = x + iy[/math].

The expression [math]x + iy[/math] is an abbreviation for the more formal [math]x' + iy'[/math]. Hence

Example

If [math]z_{1} = 4 + i3, z_{2} = 4 - i3[/math], and [math]z_{3} = 7 - i2[/math], then find [math]z_{1} + z_{2}, z_{1}z_{2}, 3z_{1} - 2z_{3}[/math], and [math]z_{1}z_{3}[/math]. These are simply routine exercises involving the addition, subtraction, and multiplication of complex numbers.

Example

If [math]z_{1} = 2 + i3[/math] and [math]z_{2} = 3 - i[/math], plot [math]z_{1}, z_{2}[/math], and [math]z_{1} + z_{2}[/math] on the complex plane. We have

and the three points are shown in Figure 19.

A complex number is a point in the [math]xy[/math]-plane and can be indicated in a picture by a dot. Another useful geometric representation of [math]z[/math] is an arrow with its tail at the origin and its head at the point [math]z[/math]. We have drawn these arrows in Figure 19. Note that if $P$ is the parallelogram whose adjacent sides are the arrows representing $z_1$ and $z_2$, then the diagonal of $P$ which has the origin as an endpoint is the arrow representing the sum $z_{1} + z_{2}$. The definition of addition in [math]C[/math] implies that this parallelogram principle is valid for every pair of complex numbers. It provides a good method for adding complex numbers geometrically. When the complex number [math]i[/math] was first introduced in mathematics, it was regarded as highly mysterious and was called an imaginary number, and this terminology has survived. If [math]z = x + iy[/math] is an arbitrary complex number, then by definition [math]x[/math] is the real part of [math]z[/math], and [math]y[/math] is the imaginary part of [math]z[/math]. Note that the imaginary part of a complex number is a real number. A complex number whose real part is zero, i.e., one that lies on the [math]y[/math]-axis, is called pure imaginary. It is important to remember that

Two complex numbers are equal if and only if their real parts are equal and their imaginary parts are equal. That is, [math]x_{1} + iy_{1} = x_{2} + iy_{2}[/math] if and only if [math]x_{1} = x_{2}[/math] and [math]y_{1} = y_{2}[/math].

We know that [math]x_{1} + iy_{1} = (x_{1}, y_{1})[/math] and [math]x_{2} + iy_{2} = (x_{2}, y_{2})[/math]. But two ordered pairs are equal if and only if their first coordinates are equal and their second coordinates are equal, and so (6.9) is proved. Another proof, which uses only the algebraic properties of complex numbers rather than their explicit construction as ordered pairs, is the following. Suppose that [math]x_{1} + iy_{1} = x_{2} + iy_{2}[/math]. Then [math]x_{1} - x_{2} = i(y_{2} - y_{1})[/math], and squaring both sides we obtain

The absolute value, or modulus, of a complex number [math]z = x + iy[/math] is a nonnegative real number denoted by [math]|z|[/math] and defined by

The geometric significance of [math]|z|[/math] is that it is the distance between the point [math]z[/math] and the origin in the complex plane. If [math]z[/math] is represented by an arrow, then [math]|z|[/math] is the length of the arrow. Note that if [math]z[/math] is real, i.e., if its imaginary part is equal to zero, then the absolute value of [math]z[/math] is simply its absolute value as a real number. Thus, if [math]z = x + iy[/math] and [math]y = 0[/math], then

An important property of the absolute value is the following.

The absolute value of the product of two complex numbers is the product of their absolute values; i.e., [math]|z_{1}z_{2}| = |z_{1}| |z_{2}|[/math].

Let [math]z_{1} = x_{1} + iy_{1}[/math] and [math]z_{2} = x_{2} + iy_{2}[/math]. Then we have [math]z_{1}z_{2} = x_{1}x_{2} - y_{1}y_{2} + i(x_{1}y_{2} + x_{2}y_{1})[/math]. Hence, by the definition of absolute value,

As an illustration of Theorem (6.10), consider the complex numbers and [math]z_{2}[/math] shown in Figure 19. The product [math]z_{1}z_{2}[/math] is equal to

The absolute values are

which is in agreement with (6.10).

If [math]z = x + iy[/math], then the complex conjugate of [math]z[/math], denoted by \={z},

is defined to be the complex number

The product of a complex number and its complex conjugate is always a nonnegative real number, since

Since [math]x^2 + y^2 = |z|^2[/math], we obtain the formula

The complex conjugate is a useful tool for computing the real and imaginary parts of the quotient of two complex numbers. If [math]z_{1}[/math] and [math]z_{2}[/math] are given and if [math]z_{2} \neq 0[/math], then

and the denominator of the right side is a real number.

Example

Compute the real and imaginary parts of the complex number [math]7 + i2[/math]. The complex conjugate of [math]7 - i2[/math] is the number [math]7 + i2[/math]. Hence

Since [math](5 + i3)(7 + i2) = 35 - 6 + i21 + i 10 = 29 + i31[/math], we obtain

Thus the real part is [math]\frac{29}{53}[/math], and the imaginary part is [math]\frac{31}{53}[/math].

\end{exercise}

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.