Integrals of Velocity and Acceleration

In this section we shall develop some of the integral formulas associated with velocity and acceleration. Among these is the formula for the distance traveled by an object, or particle, which moves with velocity [math]v(t)[/math] during the time interval from [math]t = a[/math] to [math]t = b[/math]. Consider a particle which, during some interval of time, moves along a straight line. We take the straight line to be a coordinate axis of real numbers, and denote the position of the particle on the line at time [math]t[/math] by [math]s(t)[/math]. Thus [math]s[/math] is a real-valued function of a real variable with value [math]s(t)[/math] for every [math]t[/math] in some interval. We shall assume that [math]s[/math] is differentiable. In Section 3 of Chapter 2 the velocity [math]v[/math] of the particle is defined to be the derivative of [math]s[/math]. That is,

Equivalent to this equation is the statement that [math]s[/math] is an antiderivative of [math]v[/math]. It follows that

If we consider the motion of the particle from [math]t = a[/math] to [math]t = b[/math], and add the assumption that [math]v[/math] is continuous on [math][a, b][/math], then, by Corollary (5.3) of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus (see page 204), we obtain the formula

Example

An object dropped from a cliff at time [math]t = 0[/math] falls with a velocity given by [math]v(t) = kt[/math]. If we take the direction of increasing distance to be downward, and measure distance in feet and time in seconds, then [math]k = 32[/math] and [math]v(t)[/math] is in units of feet per second. How high is the cliff if the object hits the bottom 3 seconds after being dropped? The height equals the difference [math]s(3) - s(0)[/math]. Hence

Acceleration is defined in Section 3 of Chapter 2 to be the derivative of velocity. Thus

and, as before, an equivalent statement is that velocity is an antiderivative of acceleration. We therefore have the formula

Example

A body in free fall under the earth's gravitational pull falls with a constant acceleration [math]g[/math], equal in magnitude to 32 feet per second per second. Suppose that at time [math]t = 0[/math] a ball is projected straight up from the ground with an initial velocity [math]v_0[/math] = 256 feet per second. Write formulas for the subsequent velocity [math]v(t)[/math] and distance from the ground [math]s(t)[/math]. What is the maximum height the ball attains? In this example we shall choose the direction of increasing distance to be upward. As a result, the gravitational acceleration is negative, and the starting point of our calculations is the equation [math]a(t) = - 32[/math]. We have

whence

The initial velocity is given as [math]v_0= v(0)= 256[/math] feet per second. Hence [math]c = 256[/math] and

which is one of the formulas asked for. The second integration yields

The constant of integration [math]c[/math] in the preceding equations has, of course, nothing to do with the one obtained from integrating [math]a(t)[/math]. Here [math]s(0) = -16 \cdot 0^{2} + 256 \cdot 0 + c = c[/math]. Since the ball is at ground level when [math]t = 0[/math], we conclude that [math]0 = s(0) = c[/math], and so

which is the second formula required. To find the maximum value of the function [math]s[/math], we compute its derivative and set it equal to zero:

whence it follows that

Since [math]s''(t) = v'(t) = a(t) = - 32[/math], which is negative, we know that [math]s[/math] has a local maximum when [math]t = 8[/math], and it is easy to see that this local maximum is an absolute maximum. Thus the maximum height attained by the ball is equal to

It is important to realize that the quantity [math]s(b) - s(a)[/math] in (2) does not necessarily equal the distance traveled by the object, or particle, during the time interval from [math]t = a[/math] to [math]t = b[/math]. This is because the number [math]s(t)[/math] simply gives the position of the particle on the line at time [math]t[/math]. Thus in the preceding example of the ball we showed that

Substituting [math]t = 0[/math] and [math]t = 16[/math], respectively, we get

The interpretation of these equations is clear: The ball left the ground at time [math]t = 0[/math], and 16 seconds later it had fallen back. However, an insect who accompanied the ball on its flight would probably not report to his admiring friends and relatives that the total distance traveled was

A similar situation is an automobile trip 10 miles down a road and back again. The distance traveled is presumably 20 miles, and not zero. It is not hard to guess the proper mod)fication of formula (2) to obtain a true distance formula. If we denote the distance traveled during the time interval from [math]t = a[/math] to [math]t = b[/math], where [math]a \leq b[/math], by [math]distance|_{a}^{b}[/math], then

Logically, however, there is no way to prove (4), since we have not given a mathematical definition of [math]distance|_{a}^{b}[/math]. As a result, we shall take (4) as a definition after checking that it corresponds to our intuition. First of all, if [math]v(t)[/math] does not change sign from [math]t = a[/math] to [math]t = b[/math], then

(See Problem 4 at the end of this section.) Hence, by formula (2),

The assumption that [math]v(t)[/math] does not change sign means that the direction of the motion does not change. In this case, we would certainly expect [math]|s(b) - s(a)|[/math], which equals the distance on the real line between the initial position [math]s(a)[/math] and the final position [math]s(b)[/math], to be the total distance traveled. Further motivation for the definition in formula (4) is obtained by going back to the definition of the definite integral. We assume that the function [math]|v(t)|[/math] is integrable over the interval [math][a, b][/math]. Consider an arbitrary partition [math]\sigma = \{ t_0,..., t_n \} [/math] of [math][a, b][/math] such that

For each [math]i = 1,..., n[/math], we denote by [math]M_i[/math] the least upper bound of the set of all numbers [math]|v(t)|[/math], where [math]t[/math] is in the subinterval [math][t_{i-1}, t_i][/math]. Similarly, let [math]m_i[/math] be the greatest lower bound. Thus the number [math]M_i[/math] is the maximum speed of the particle in the subinterval [math][t_{i-1}, t_i][/math], and [math]m_i[/math] is the minimum speed. Intuitively, therefore, the distance traveled by the particle during the sub interval of time [math][t_{i-1}, t_i][/math] must be less than or equal to [math]M_i(t_{i} - t_{i - 1})[/math] and greater than or equal to [math]m_i(t_{i} - t_{i - 1})[/math]. Consequently, the upper and lower sums,

are upper and lower bounds, respectively, of the total distance traveled. But the function [math]|v(t)|[/math] has been assumed to be integrable over [math][a, b][/math]. It follows that there exists one and only one number, [math]\int_{a}^{b} |v(t)| dt[/math], such that

for every partition [math]\sigma[/math] of [math][a, b][/math]. This just)fies the adoption of formula (4) as the definition of [math]distance|_{a}^{b}[/math].

Example

A particle moves on the [math]x[/math]-axis, and its position at time [math]t[/math] is given by [math]x(t) = 2t^3 - 21t^2 + 60t - 14[/math]. Its velocity is the function [math]v[/math] defined by

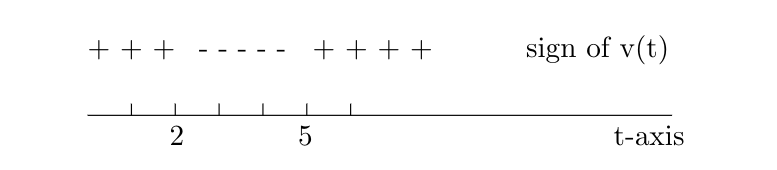

Find the total distance traveled by the particle during the time interval [math]t = 0[/math] to [math]t = 6[/math]. Clearly, [math]v(t) = 0[/math] when [math]t = 2[/math] and [math]t = 5[/math], and the sign of [math]v(t)[/math] is as indicated by

Hence

Consequently,

Since [math]x(t)[/math] is an antiderivative of [math]v(t)[/math],

and so

Substitution in the equation for [math]x(t)[/math] yields [math]x(0) = - 14[/math], [math]x(2)= 38[/math], [math]x(5) = 11[/math], and [math]x(6) = 22[/math]. Hence

The motion described in this example is the same as in Example 1, page 105. By looking at Figure, one can see that the distance traveled by the particle during the time interval [0, 6] agrees with the value just obtained.

The integral formulas derived in this section all presuppose motion along a straight line. The reason for this restriction is that the definition of velocity, and consequently of acceleration, has been based on the possibility of representing the position of the particle at time [math]t[/math] by a real number [math]s(t)[/math] along a coordinate axis. A coordinate system on a line in turn is defined in terms of the distance between two points, and thus far the only measure of distance between points which we have is straight-line distance. ln Chapter 10 we shall introduce the notion of arc length along a curve and shall study the notions of velocity and acceleration for curvilinear motion. At this point, however, it is worth noting that if we think of obtaining a curve by bending a coordinate axis without stretching it, and if [math]s(t)[/math] measures position on the curve in the obvious way, then formulas (1), (2), (3), and (4) still hold. Thus if the speedometer reading on a car is given by some nonnegative and integrable function [math]f[/math] of time, then the distance traveled during the time interval [math][a, b][/math] is equal to [math]\int_{a}^{b} f(t) dt[/math] whether the road is straight or not.

We conclude this section with another type of problem illustrating the integration of rates of change.

Example

Air is escaping from a spherical balloon so that its radius [math]r[/math] is decreasing at the rate of 2 inches per minute. Find the rate of change of the volume [math]V[/math] as a function of time if we are given that [math]r = 10[/math] inches when [math]t = 0[/math]. What is the volume of the balloon when [math]t = 2[/math] minutes, and at what time will [math]V = 0[/math]? The volume of a sphere is given by [math]V = \frac{4}{3} \pi r^3[/math], and we are given that

Hence

Setting [math]t = 0[/math], we see that the constant of integration [math]c[/math] is the value of the radius at [math]t = 0[/math], namely, 10 inches. Hence

Since

we obtain for the answer to the first part of the problem

where [math]t[/math] is measured in minutes and [math]\frac{dV}{dt}[/math] in cubic inches per minute. Clearly,

The volume of the balloon when [math]t = 2[/math] minutes is therefore

and the volume will be zero when

i.e., when [math]t = 5[/math] minutes.

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.