Vectors in the Plane

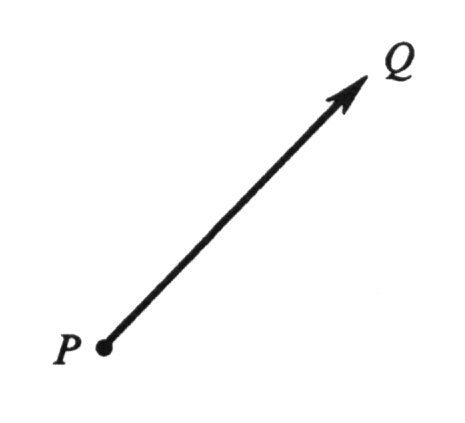

A vector in the plane is an ordered pair [math](P, Q)[/math] of points in the plane. The point [math]P[/math] is called the initial point of the vector and [math]Q[/math] the terminal point. Geometrically, the vector [math](P, Q)[/math] will be represented as a directed line segment, or arrow, from [math]P[/math] to [math]Q[/math], as illustrated in Figure 10. We shall use boldface lower-case letters to denote vectors. For example, if [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is the vector with initial point [math]P[/math] and terminal point [math]Q[/math], then [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} = (P, Q)[/math].

Having identified the plane with the set [math]R^2[/math] of all ordered pairs of real numbers, we see that a vector is determined by four real numbers: two coordinates of its initial point, and two of its terminal point. Let [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] be a vector with initial point [math]P = (a, b)[/math] and terminal point [math]Q = (c, d)[/math]. Then the two numbers [math]v_1[/math] and [math]v_2[/math] given by the equations

are defined to be first and second coordinates, respectively, of the vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]R^2[/math]. Thus we have defined coordinates of a vector in [math]R^2[/math] as well as coordinates of a point in [math]R^2[/math]. The definitions are not the same, although the concepts are certainly related.

If a vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] has initial point [math]P = (a, b)[/math] and coordinates [math]v_1[/math] and [math]v_2[/math], then equations (1) tell us that the terminal point [math]Q = (c, d)[/math] is given by

It follows that a vector is completely determined by its initial point and its coordinates. Hence, another notation for a vector, which we shall use, is \setcounter{equation}{1}

[Although it would be consistent with this notation, we shall not write [math](v_1, v_2)_{(a,b)}[/math] for the vector with initial point [math](a, b)[/math] and coordinates [math]v_1[/math] and [math]v_2[/math].] The length of a vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} = (P, Q)[/math] in [math]R^2[/math] is denoted by [math]|\mbox{\bf{v}}|[/math] and defined by

If [math]P = (a, b)[/math] and [math]Q = (c, d)[/math], then the formula for the distance between two points implies that

From equations (1) it follows that the coordinates of the vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] are the two numbers [math]v_1 = c - a[/math] and [math]v_2 = d - b[/math]. Hence

The length of any vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} = (v_1, v_2)_P[/math] is given by

Thus the length of a vector depends only on its coordinates.

Example

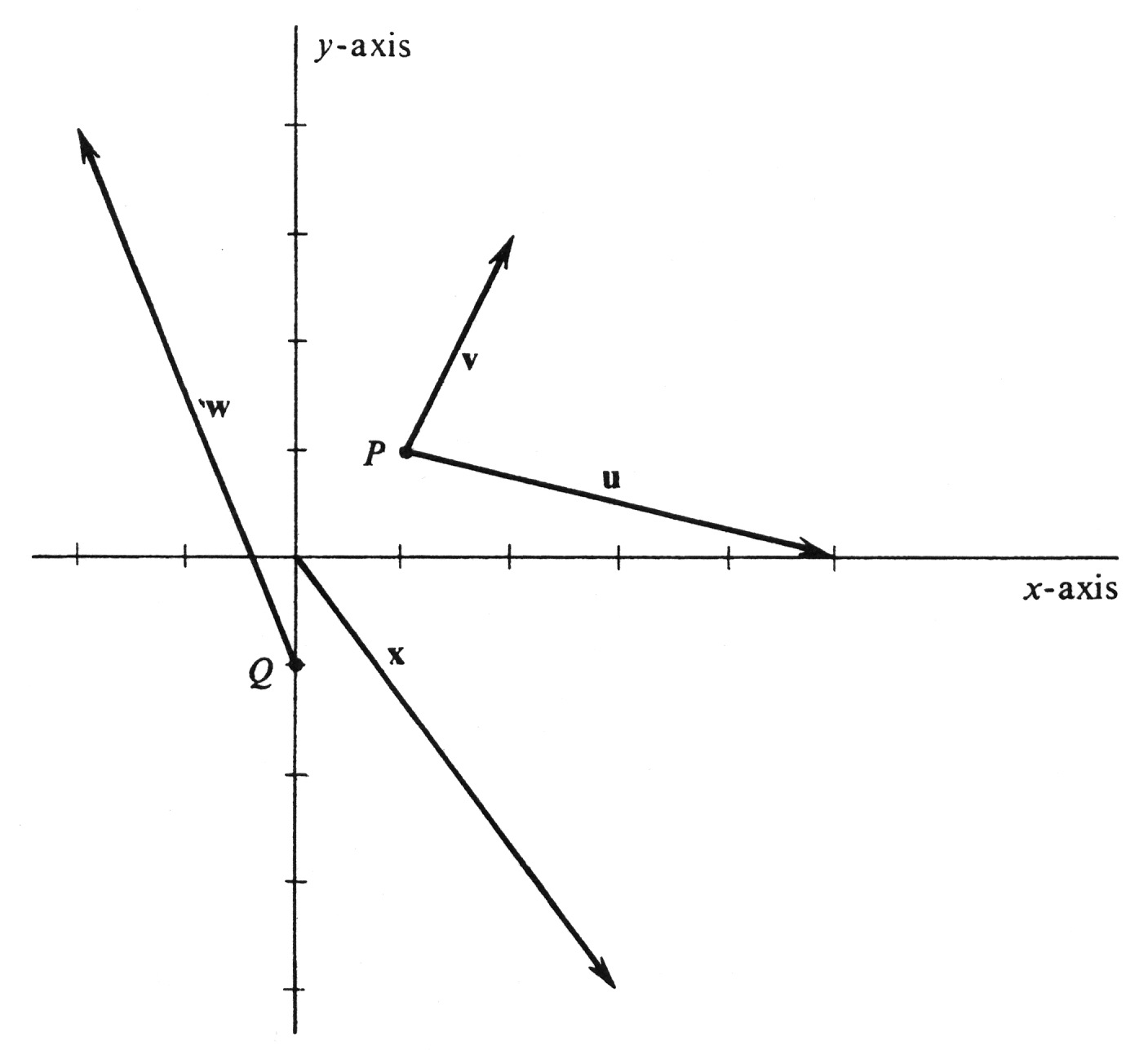

Find the terminal point of each of the following vectors. Draw each one as an arrow in the [math]xy[/math]-plane, and compute its length.

- [math]\textbf{v}\; = (1, 2)_P, \;\;\mathrm{where}\; P = (1, 1),[/math]

- [math]\textbf{u}\; = (4, -1)_P, \;\;\mathrm{where}\; P = (1, 1),[/math]

- [math]\textbf{w}\; = (-2, 5)_Q,\;\;\mathrm{where}\; Q = (0, -1),[/math]

- [math]\textbf{x}\; = (3, -4)_O, \;\;\mathrm{where}\; O = (0, 0).[/math]

We have seen that, if [math]P = (a, b)[/math], then the terminal point of the vector [math](v_1, v_2)_P[/math] is the ordered pair [math](a + v_1, b + v_2)[/math]. It follows that

The vectors are drawn in Figure 11. Their respective lengths, computed from the formula in (3.1), are

We shall denote the set of all vectors in [math]R^2[/math] by [math]\mathcal{V}[/math]. For every point [math]P[/math] in [math]R^2[/math], the subset of [math]\mathcal{V}[/math] consisting of all vectors with initial point [math]P[/math] will be denoted by

[math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math]. We shall now define, in each set [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math], an operation of addition of vectors and an operation of multiplication of vectors by real numbers.

Addition in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] is defined as follows: If [math]\mbox{\bf{u}} = (u_1, u_2)_P[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} = (v_1, v_2)_P[/math] are any two vectors in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math], then their sum [math]\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is the vector defined by

Note that the sum of two vectors in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] is again a vector in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math]. Furthermore, if [math]\mbox{\bf{u}}[/math] is in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is in [math]\mathcal{V}_Q[/math], then their sum is not defined unless [math]P = Q[/math]. That is, the sum of two vectors is defined if and only if they have the same initial point. For every vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} = (v_1, v_2)_P[/math], we denote the vector [math](-v_1, -v_2)_P[/math] by [math]-\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math]. In this way, subtraction of vectors in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] is defined by the equation

which implies the following companion formula to (3):

The unique vector in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] with both coordinates equal to zero is called the zero vector and will be denoted by [math]\mbox{\bf{0}}[/math]. Thus

Obviously, the equations

are true for every vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math]. Geometrically the zero vector in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] is represented simply by the point [math]P[/math]. Of course, there are as many different zero vectors as there are points in the plane, and one cannot tell from the notation [math]\mbox{\bf{0}}[/math] to which set [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] a given zero vector belongs. It is obvious that every zero vector has length zero. Conversely, the length of a nonzero vector must be positive, since at least one of its coordinates is not zero. Hence

A vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is a zero vector if and only if [math]|\mbox{\bf{v}}| = 0[/math].

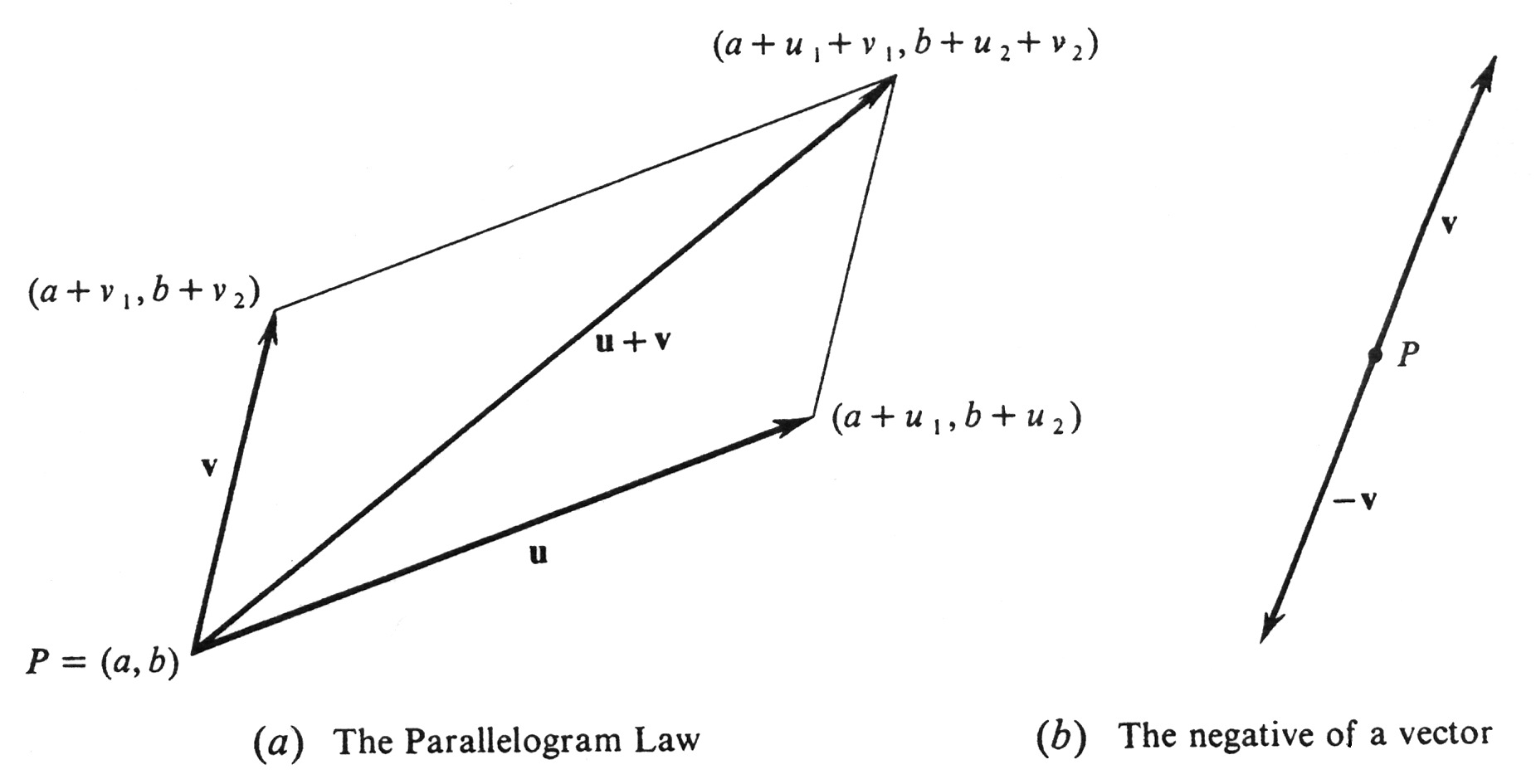

Geometrically, the sum [math]\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] of two nonzero vectors [math]\mbox{\bf{u}}[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] is the vector in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] which is a diagonal of the parallelogram which has [math]\mbox{\bf{u}}[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] as sides. This is the famous Parallelogram Law and is illustrated in Figure 12(a). It can be verified in a straightforward way by computing the slopes of the various line segments, and we omit the details. Similarly, the vector [math]-\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is represented geometrically as a directed line segment Iying in the same straight line as [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], but in the opposite direction, as shown in Figure 12(b). Moreover, the vectors [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] and [math]-\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] have the same length, since

The second algebraic operation in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] is defined as follows: For every real number [math]a[/math] and every vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} = (v_1, v_2)_P[/math] in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math], we define a vector [math]a\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], called the product of [math]a[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], by the equation

In traditional vector terminology, the real number [math]a[/math] is called a scalar. Note that we have not defined a product of two vectors. If we compute the length of the vector [math]a\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], we find that

a result which we summarize in the statement

[math]|a\mbox{\bf{v}}| = |a| \; |\mbox{\bf{v}}|[/math], for every real num ber [math]a[/math] and every vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math].

If [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is an arbitrary nonzero vector in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] and if [math]a \neq 0[/math], then the slope of the line segment joining [math]P[/math] to the terminal point of [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is the same as that joining [math]P[/math] to the terminal point of [math]a\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math]. Hence [math]P[/math] and the terminal points of [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] and [math]a\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] lie on the same straight line. In addition, it is easy to check that the arrows representing [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] and [math]a\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] are in the same or opposite direction according as a is positive or negative.

Example

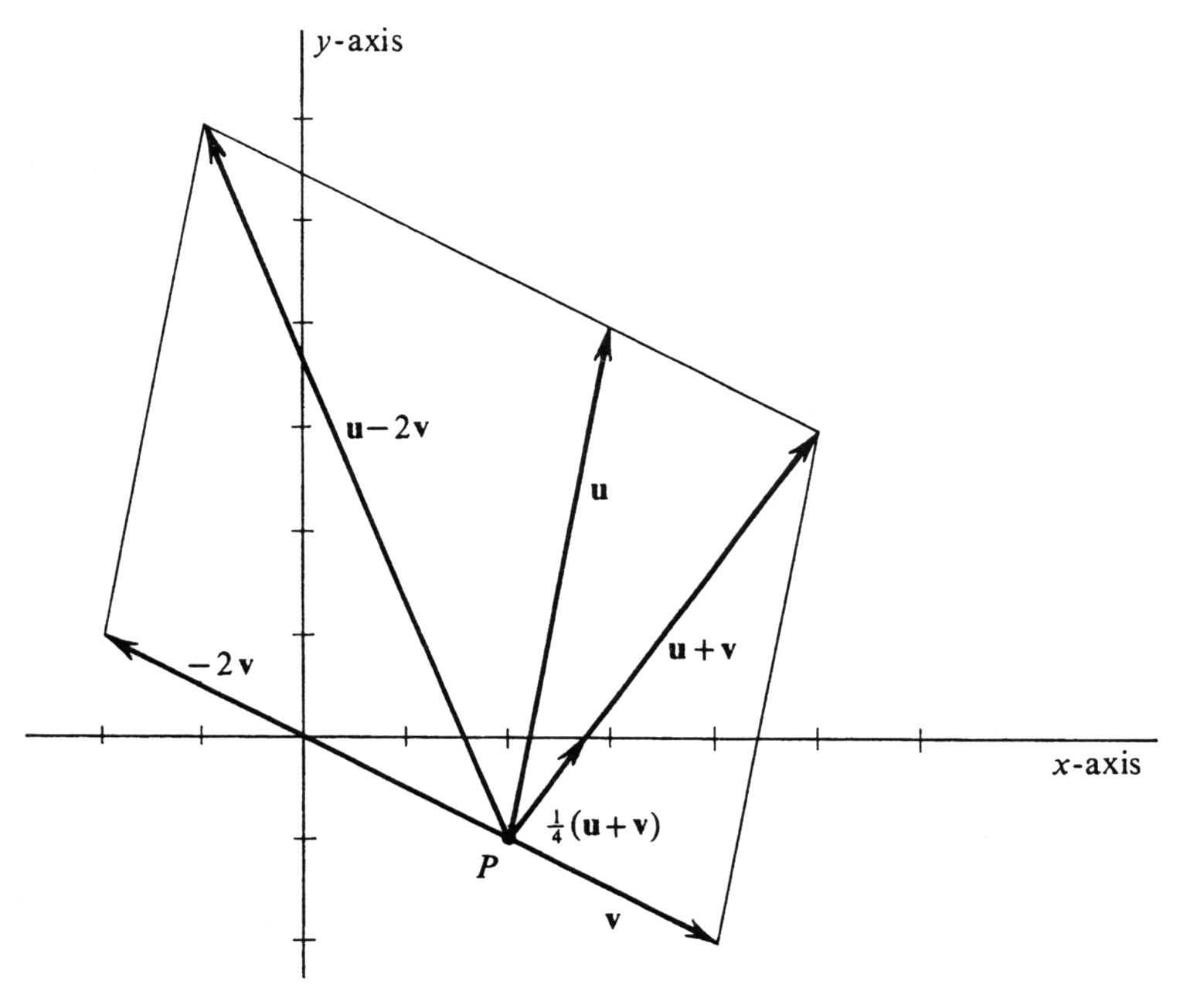

Let [math]P = (2, -1)[/math] and consider the two vectors [math]\mbox{\bf{u}} = (1, 5)_P[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} = (2, -1)_P[/math]. Compute and draw each of the following vectors in the same plane with [math]\mbox{\bf{u}}[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math].

- [math]\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}, [/math]

- [math]-2\mbox{\bf{v}},[/math]

- [math]\mbox{\bf{u}} - 2\mbox{\bf{v}},[/math]

- [math]\frac{1}{4}(\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}).[/math]

The computations are very simple:

The directed line segments representing these vectors, as well as [math]\mbox{\bf{u}}[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], are shown in Figure 13. The easiest way to draw them is to make a list of their terminal points. We recall that a vector with coordinates [math]v_1[/math] and [math]v_2[/math] and initial point [math]P = (a, b)[/math] has a terminal point equal to [math](a + v_1, b + v_2)[/math]. Hence

The next theorem summarizes the algebraic facts about the set [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] of all vectors in the plane with initial point [math]P[/math].

For each point [math]P[/math] in [math]R^2[/math], vector addition and scalar multiplication in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] have the following properties:

-

ASSOCIATIVITY

[[math]] \mbox{\bf{u}} + (\mbox{\bf{v}} + \mbox{\bf{w}}) = (\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}) + \mbox{\bf{w}}\;\;\; \mbox{and}\;\;\; (ab)\mbox{\bf{v}} = a(b\mbox{\bf{v}}). [[/math]]

-

COMMUTATIVITY

[[math]] \mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}} = \mbox{\bf{v}} + \mbox{\bf{u}}. [[/math]]

- EXISTENCE OF ADDITIVE IDENTITY There exists a vector [math]\mbox{\bf{0}}[/math] in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] with the property that [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} + \mbox{\bf{0}} = \mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], for every vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math].

- EXISTENCE OF SUBTRACTION For every vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math], there exists a vector [math]-\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] such that [math]\mbox{\bf{v}} + (-\mbox{\bf{v}}) = \mbox{\bf{0}}[/math].

-

DISTRIBUTIVITY

[[math]] a(\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}) = a\mbox{\bf{u}} + a\mbox{\bf{v}} \;\;\;\mbox{and}\;\;\; (a + b)\mbox{\bf{v}} = a\mbox{\bf{v}} + b\mbox{\bf{v}}. [[/math]]

-

EXISTENCE OF SCALAR IDENTITY

[[math]] 1\mbox{\bf{v}} = \mbox{\bf{v}}. [[/math]]

The proof of this theorem follows easily from the definitions of vector addition and scalar multiplication, from the definitions of [math]\mbox{\bf{0}}[/math] and [math]-\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], and from the corresponding properties of addition and multiplication of real numbers given on page 2. The importance of the theorem is that every algebraic fact about vectors can be derived from the six properties listed. In fact, in abstract algebra, these properties are taken as a set of axioms: An arbitrary set [math]\mbox{\bf{V}}[/math] is called a vector space and its elements are called vectors if, for every pair of elements [math]\mbox{\bf{u}}[/math] and [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]\mbox{\bf{V}}[/math] and for every real number a, an element [math]\mbox{\bf{u}} + \mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] and an element [math]a\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] in [math]\mbox{\bf{V}}[/math] are defined so that conditions (i) through (vi) are satisfied. This definition has proved to be of enormous value in mathematics and examples of vector spaces occur over and over again. In particular, Theorem (3.4) asserts that, for each point [math]P[/math] in [math]R^2[/math], the set [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math] is a vector space.

Example

Let [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] be a nonzero vector in [math]R^2[/math]. Then the set, which we shall denote by [math]R\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], consisting of all products [math]t\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], where [math]t[/math] is a real number, is an example of a vector space. For, if [math]P[/math] is the initial point of [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math], then [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] lies in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math], and it follows that every product [math]t\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] also lies in [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math]. Hence the sum of any two vectors in [math]R\bf{v}[/math] is defined, and, since

the sum is again in [math]R\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math]. Similarly, if [math]t\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is in [math]R\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] and if [math]s[/math] is any real number, then

and [math](st)\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is by definition in [math]R\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math]. Thus vector addition and scalar multiplication are defined in the set [math]R\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math]. Conditions (i), (ii), (v), and (vi) are automatically satisfied because they hold in the larger set [math]\mathcal{V}_P[/math]. Finally, conditions (iii) and (iv) are also satisfied, since

This completes the proof that [math]R\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] is a vector space. The terminal points of all the vectors in [math]R\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math] form the straight line containing the initial and terminal points of the vector [math]\mbox{\bf{v}}[/math].

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.