Approximate Values

Approximate Values.

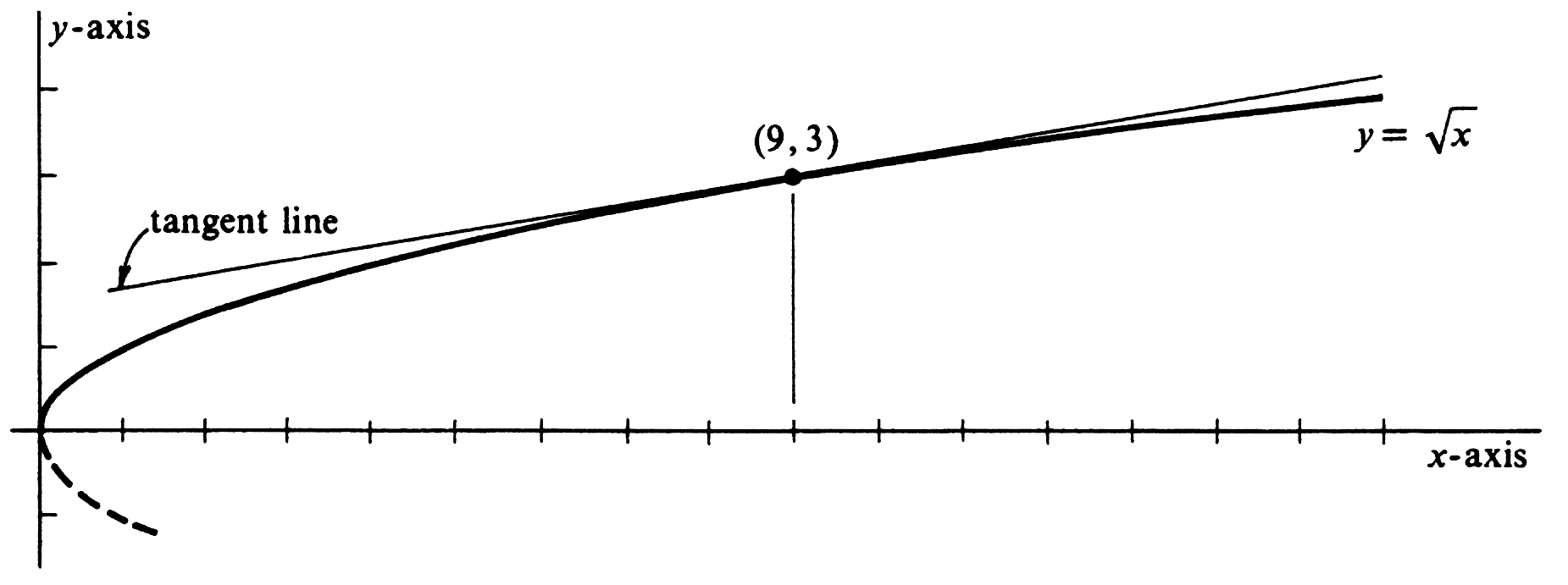

If we can find the values of a function and its derivative at some particular number a, then there is a useful method for obtaining an approximation to the value of the function at any number near [math]a[/math]. For example, knowing that [math]\sqrt 9 = 3[/math], we can easily obtain a good approximation to [math]\sqrt 9.1[/math]. Similarly, we can use this method to find simple approximations to such numbers as [math]\frac{1}{4.02}[/math], [math]\sqrt[3]{26.8}[/math], and [math](32.1)^{1/5}[/math]. To obtain the approximation for [math]\sqrt 9.1[/math], we consider the graph of the function [math]f[/math] defined by [math]f(x) = \sqrt x[/math] and drawn in Figure 17. The tangent line to the curve at the point (9, 3) touches the curve at that point and is not very far away from it for values of [math]x[/math] near 9. Although it is tedious to find a decimal approximation for the ordinate of the point on the curve [math]y = \sqrt x[/math] with an abscissa of 9.1, it is relatively easy to find one for the point on the tangent line with that abscissa, and the two points are not very far apart. Since [math]\frac{d}{dx} \sqrt x = \frac{1}{2 \sqrt x}[/math], the tangent line has a slope of [math]\frac{1}{2 \sqrt 9} = \frac{1}{6}[/math] and has an equation

If [math]x = 9.1[/math], [math]y = 3 + \frac{1}{6}(0.1) = 3\frac{1}{60}[/math], or 3.017. Thus 3.017 is our approximation for [math]\sqrt 9.1[/math]. That it is a good approximation may be seen by checking a table of square roots to find [math]\sqrt 9.1 = 3.016621[/math]. The same tangent line may be used to approximate [math]\sqrt 10[/math], but the accuracy will not be as good. If [math]x = 10[/math], [math]y = 3 + \frac{1}{6} = 3.167[/math]. The tables give 3.162278 for [math]\sqrt 10[/math]. The technique used in the problem above is the computation of an approximate value of [math]f(x)[/math] under the assumption that the difference [math]x - a[/math] is small in absolute value and that both [math]f(a)[/math] and [math]f'(a)[/math] are known, or can be easily evaluated. We write an equation of the tangent line to the graph of the function [math]f[/math] at [math](a, f(a))[/math] and take the ordinate of the point on the line with abscissa [math]x[/math] as the approximation tof(x). The tangent line has equation [math]y - f(a) = f'(a)(x - a)[/math], or, equivalently,

The function [math]f(a) + f'(a)(x - a)[/math] is a linear function of [math]x[/math], and is the linear function which best approximates [math]f(x)[/math] for values of [math]x[/math] near [math]a[/math]. The approximation consists of simply replacing the true value [math]f(x)[/math] by the corresponding value of the linear function. The result is summarized in the formula

in which it is assumed that [math]|x-a|[/math] is small and the symbol [math]\approx[/math] indicates approximate equality. \medskip Example

Find an approximate value of [math]\frac{1}{4.02}[/math]. If we define [math]f(x) = \frac{1}{x}[/math], then [math]f(4) = \frac{1}{4} = 0.25[/math] is easily evaluated. Moreover, [math]f'(4) = - \frac{1}{4^2} = - \frac{1}{16} = -0.0625[/math], and 0.02, the difference between 4.02 and 4, is small. Thus [math]\frac{1}{4.02}[/math] is approximately equal to [math]\frac{1}{4} - \frac{1}{16}(4.02 - 4) = 0.25 - (0.0625)(0.02) = 0.24875[/math]. \medskip Example

Compute [math]\sqrt[3]{26.8}[/math] approximately. If we let [math]f(x) = x^{1/3}[/math], then [math]f(27) = 3[/math]. Since [math]f'(x) = \frac{1}{3}x^{-2/3}[/math], we obtain [math]f'(27) = \frac{1}{3}(27)^{-2/3} = \frac{1}{27}[/math]. The difference [math]| 26.8 - 27 | = 0.2[/math] is small. Thus we approximate [math]\sqrt[3]{26.8}[/math] by [math]3 + \frac{1}{27}(26.8 - 27) = 3 + \frac{1}{27}( -0.2) = 2.9926[/math]. A table of cube roots gives a more exact value of 2.992574, but the linear approximation gives fourdecimal accuracy.

An alternative point of view is obtained if we substitute [math]x = a + t[/math] in (1). The left side of the formula becomes [math]f(a + t)[/math] and the right side is then [math]f(a) + f'(a)((a + t) - a) = f(a) + tf'(a)[/math]. Hence, we obtain the equivalent formula

which gives an approximate value of [math]f(a + t)[/math] in terms of the known quantities [math]f(a), f'(a)[/math], and [math]t[/math]. The same result can also be obtained easily from the definition of the derivative of the function [math]f[/math] at [math]a[/math],

It follows that if [math]t[/math] is nonzero and small in absolute value, then [math]f'(a)[/math] is given approximately by

which immediately implies (2).

\end{exercise}

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.