Inverse Trigonometric Functions

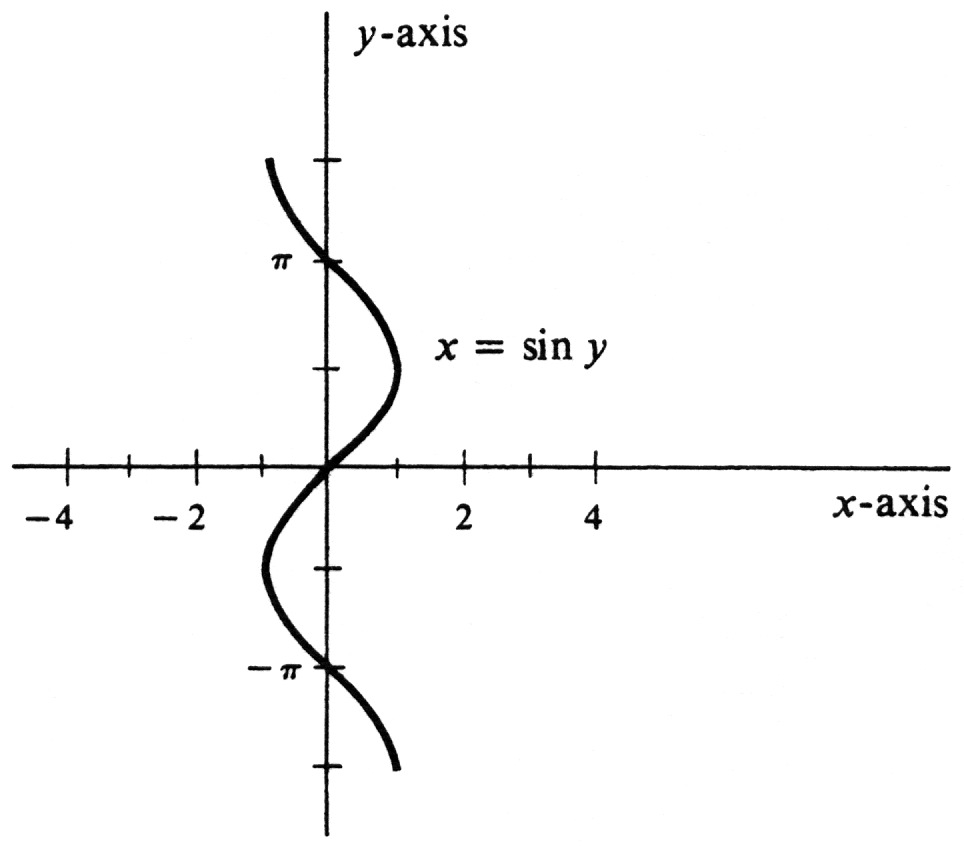

The function [math]\sin[/math] does not have an inverse function. The reason is that it is perfectly possible to have [math]a \neq b[/math] and [math]\sin a = \sin b[/math]. Another way to reach the same conclusion is to consider the equation [math]x = \sin y[/math]. Its graph is the curve in Figure 14. It does not define a function of [math]x[/math] because it does not satisfy the condition in the definition of function (see page 14) which asserts that every vertical line intersects the graph of a function in at most one point.

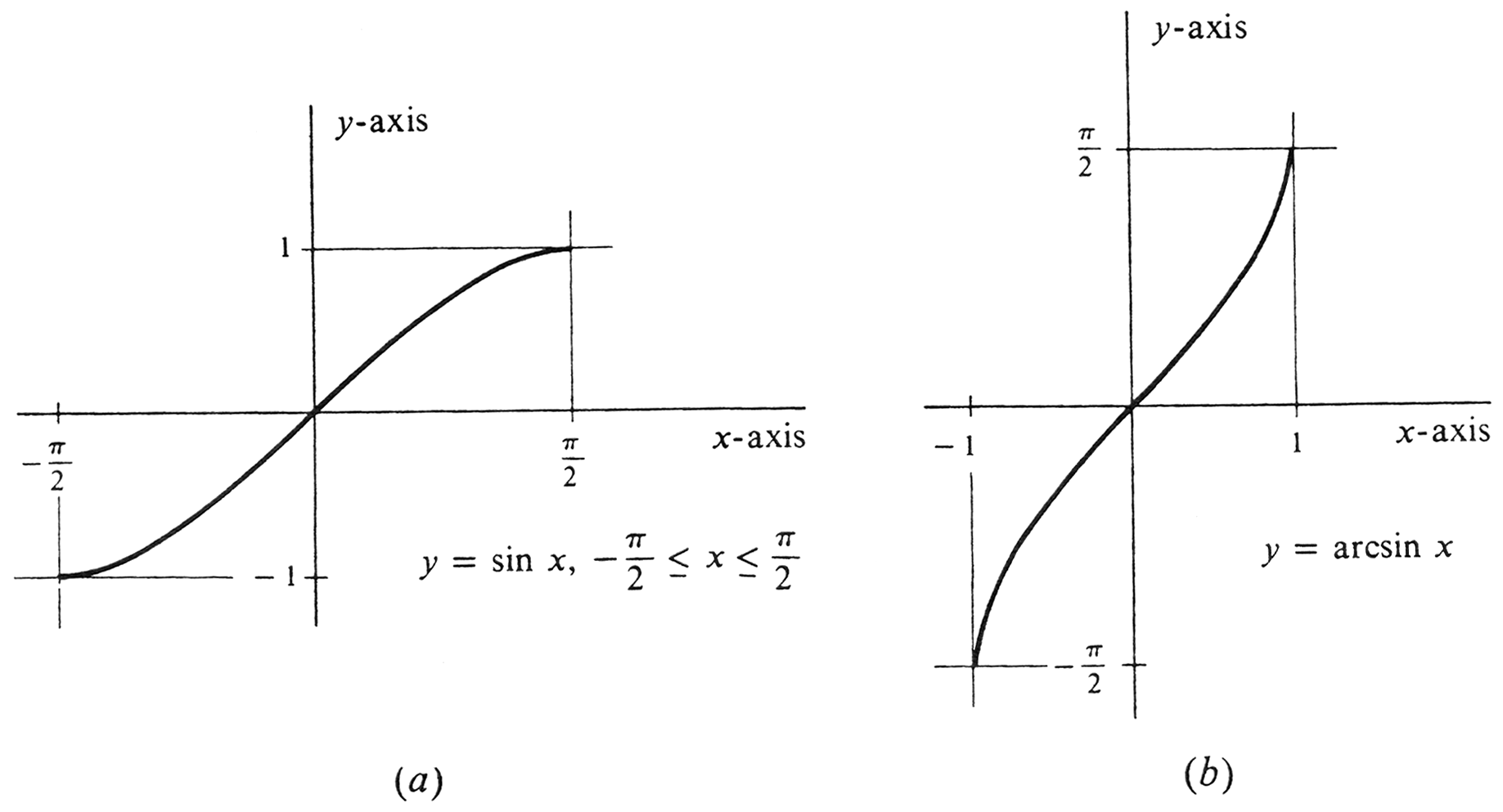

However, on the interval [math]\Bigl[-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr][/math] the function [math]\sin[/math] is a strictly increasing function. Hence, although [math]\sin[/math] does not have an inverse, it follows by Theorem (2.4), page 250, that the function [math]\sin[/math] with domain restricted to [math]\Bigl[-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr][/math] does have an inverse. This inverse function is denoted by either [math]\sin^{-1}[/math] or [math]\arcsin[/math], and in this book we shall use the latter notation. Thus

The graph of the function [math]\arcsin[/math] is shown in Figure 15(b). It is that part of the graph of the equation [math]x = \sin y[/math] for which [math]y[/math] satisfies the inequality [math]-\frac{\pi}{2} \leq y \leq \frac{\pi}{2}[/math]. Note that the graph of [math]\arcsin[/math] is obtained from the graph of the restricted function [math]\sin[/math] by reflection across the diagonal line [math]y = x[/math]. It follows both from the definition of [math]\arcsin[/math] and also from the illustration that the domain of [math]\arcsin[/math] is the closed interval [math][ -1, 1][/math] and the range is the closed interval [math]\Bigl[-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr][/math].

It is a consequence of Theorem (3.4), page 261, that the function [math]\arcsin[/math] is differentiable at every point of its domain except at -1 and +1. [In applying (3.4), let [math]f[/math] be the function [math]\sin[/math] restricted to [math]\Bigl[-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr][/math] and then [math]f^{-1} = \arcsin[/math].] We may compute the formula for the derivative either directly from (3.4) or by implicit differentiation. Choosing the latter method, we begin with [math]y = \arcsin x[/math] and seek to find [math]\frac{dy}{dx}[/math]. If [math]y = \arcsin x[/math], then [math]x = \sin y[/math], and so

Hence

To express [math]\cos y[/math] in terms of [math]x[/math], we use the identity [math]\cos^{2} y + \sin^{2} y = 1[/math] and the fact that [math]x = \sin y[/math]. Hence [math]\cos^{2} y + x^{2} = 1[/math], and therefore

However, [math]y[/math] is restricted by the inequality [math]-\frac{\pi}{2} \leq y \leq \frac{\pi}{2}[/math] and in this interval [math]\cos y[/math] is never negative. Hence the positive square root is the correct one, and we conclude that [math]\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}}[/math]. Thus

Example

Find the domain, range, and derivative of each of the composite functions

The quantity [math]\frac{1}{1 + x^2}[/math] is defined for every real number [math]x[/math] and also satisfies the inequalities [math]0 \lt \frac{1}{1 + x^{2}} \leq 1[/math]. Hence, [math]\arcsin \frac{1}{1 + x^{2}}[/math] is defined for every [math]x[/math]; i.e., its domain is the set of all real numbers. The range of the function [math]\frac{1}{1 + x^{2}}[/math], however, is the half-open interval (0, 1]. It can be seen from Figure 15(b) that the function [math]\arcsin[/math] maps the interval (0, 1] on the [math]x[/math]-axis onto the interval [math]\Bigl(0, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr][/math] on the [math]y[/math]-axis. It follows that the range of the composition [math]\arcsin \frac{1}{1 + x^{2}}[/math] is the half-open interval [math]\Bigl(0, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr][/math]. The derivative is found using (4.1) and the Chain Rule:

For any particular value of [math]x[/math], the quantity [math]\arcsin(\ln x)[/math] is defined if and only if [math]\ln x[/math] is defined and also lies in the domain of the function [math]\arcsin[/math], which is the interval [ - 1, 1]. Thus [math]x[/math] must be positive, and [math]\ln x[/math] must satisfy the inequalities [math]-1 \leq \ln x \leq 1[/math]. Hence [math]x[/math] must satisfy [math]\frac{1}{e} \leq x \leq e[/math]. The domain of [math]\arcsin (\ln x)[/math] is therefore the interval [math]\Bigl[\frac{1}{e}, e\Bigr][/math], and the range is the same as that of [math]\arcsin[/math], i.e., the interval [math]\Bigl[ -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \Bigr][/math]. The derivative is given by

The integral formula corresponding to (4.1) is

Example

Find [math]\int \frac{x dx}{\sqrt 4 - x^4}[/math]. The first thing we do is to write the denominator, as closely as possible, in the form [math]\sqrt {1 - u^2}[/math].

Hence, letting [math]u = \frac{x^2}{2}[/math], we have [math]\frac{du}{dx} = x[/math] and

By (4.2),

Finally, substituting [math]\frac{x^2}{2}[/math] for [math]u[/math], we obtain

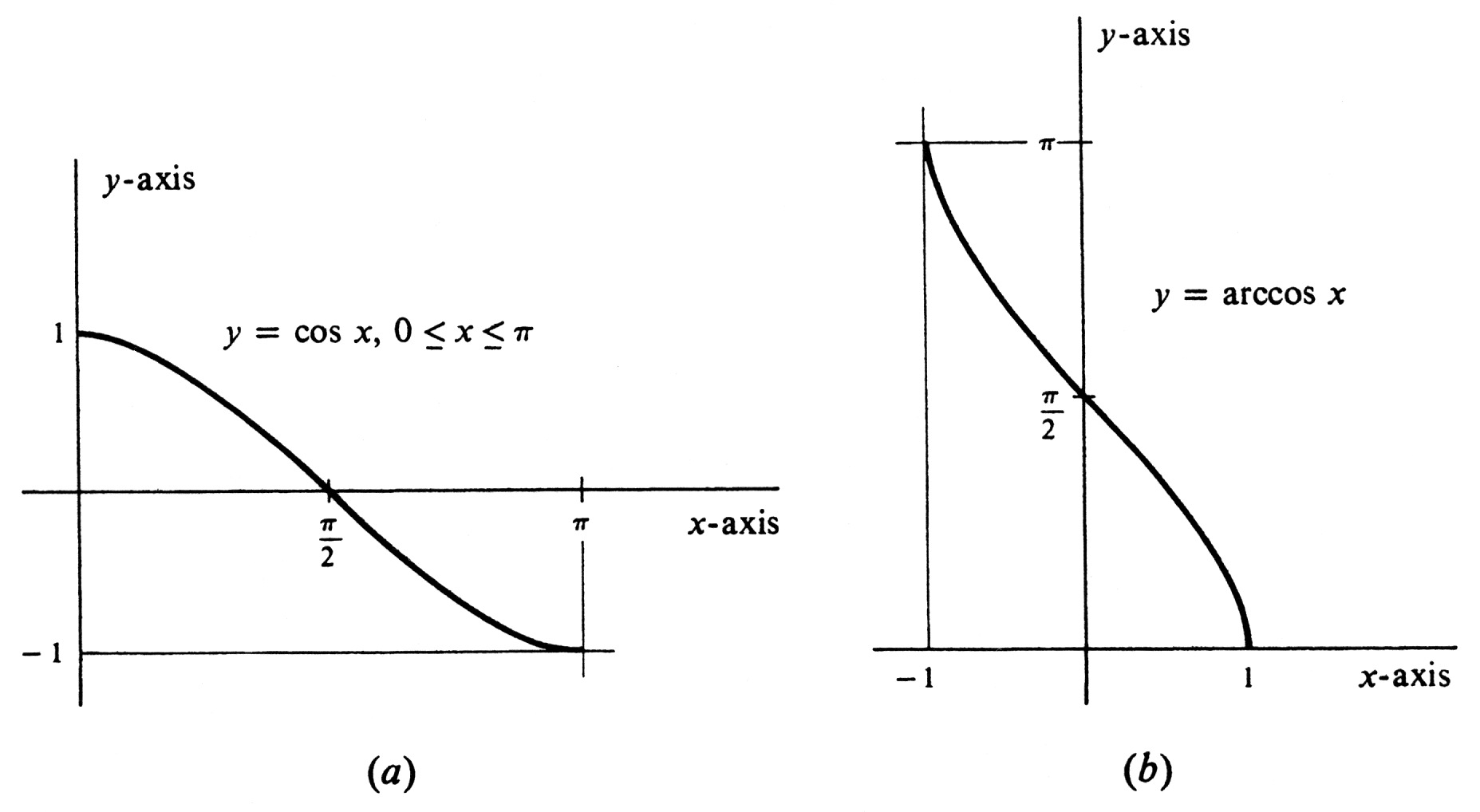

The function [math]\cos[/math] does not have an inverse for the same reason that [math]\sin[/math] does not. However, a partial inverse can be obtained, just as before, by restricting the domain to an interval on which [math]\cos[/math] is either increasing or decreasing. Any such interval can be chosen. With the function [math]\sin[/math] it was natural to choose the largest possible interval containing the number 0---the closed interval [math]\Bigl[ -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr][/math]. With [math]\cos[/math] the choice is less obvious. However, we shall select the interval [math][0, \pi][/math], on which [math]\cos[/math] is strictly decreasing [see Figure 16(a)]. The function [math]\cos[/math] with domain restricted to [math][0, \pi][/math] then has an inverse, which is denoted [math]\cos^{-1}[/math] or [math]\arccos[/math]. As before, we shall use the second notation. Thus

The graph of [math]\arccos[/math] is shown in Figure 16(b). It should come as no surprise that the two functions [math]\arcsin[/math] and [math]\arccos[/math] are closely related. In fact,

Let [math]y = \frac{\pi}{2} - \arccos x[/math]. Then [math]\arccos x = \frac{\pi}{2} - y[/math], and so [math]x = \cos \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2} - y \Bigr)[/math]. Hence

Note that the validity of (4.3) depends on our having chosen [math]\arccos[/math] so that its range is the interval [math][0, \pi][/math]. It follows from (4.3) that the derivative of [math]\arccos[/math] is the negative of the derivative of [math]\arcsin[/math]. Thus

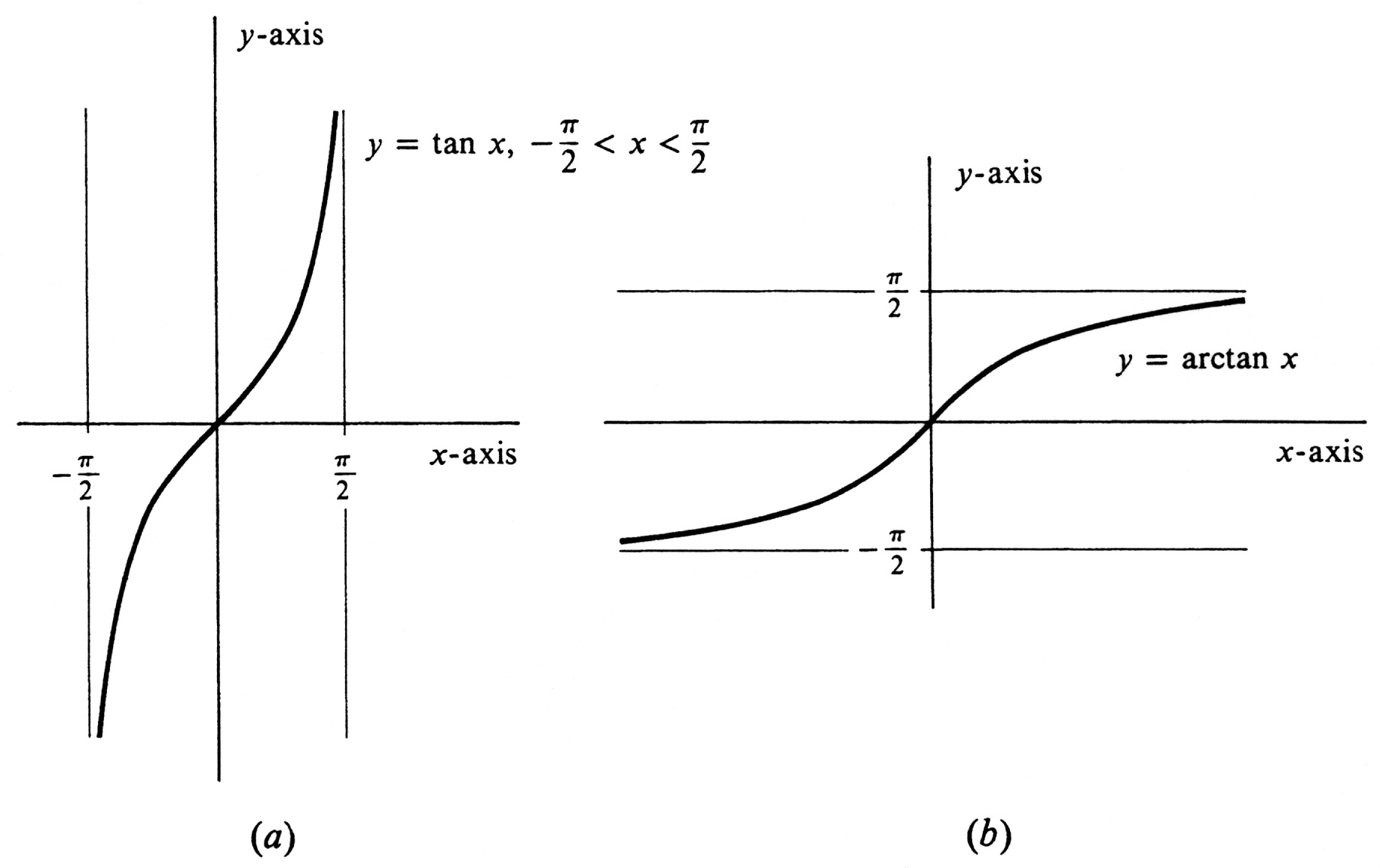

From (4.4) we see that another indefinite integral of [math]\frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - x^2}}[/math] is [math]-\arccos x[/math]. Obviously, not one of the six trigonometric functions with unrestricted domain has an inverse. The function [math]\tan[/math] with its domain restricted to the open interval [math]\Bigl( -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \Bigr)[/math] is strictly increasing and so has an inverse function, which we denote [math]\tan^{-1}[/math] or [math]\arctan[/math].

The graph of [math]\arctan[/math] is obtained by reflecting the graph of [math]\tan[/math] with domain restricted to [math]\Bigl( -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr)[/math] across the diagonal line [math]y = x[/math]. It is shown in Figure 17(b). As can be seen from Figure 17(a), the function [math]\tan[/math] maps the open interval [math]\Bigl( -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr )[/math] onto the entire set of real numbers. That is, for every real number [math]y[/math], there exists a real number [math]x[/math] in [math]\Bigl( -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \Bigr)[/math] such that [math]y = \tan x[/math]. Hence the domain of arctun is the whole real line [math]( -\infty, \infty)[/math]. The range is the interval

[math]\Bigl( -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr)[/math].

It is a corollary of Theorem (3.4), page 261, that [math]\arctan[/math] is a differentiable function. We compute the derivative by implicit differentiation. Let [math]y = \arctan x[/math]. Then [math]x = \tan y[/math], and

Hence

From the identity [math]\sec^{2} y = 1 + \tan^{2} y[/math], we get [math]\sec^{2} y = 1 + x^{2}[/math]. It follows that [math]\frac{d}{dx} = \frac{1}{1 + x^2}[/math]. Thus

The corresponding integral formula is

Example

Compute the definite integral [math]\int_{0}^{1} \frac{dx}{1 + x^2}[/math]. We get immediately

Since [math]\tan 0 = 0[/math] and [math]\tan \frac{\pi}{4} = 1[/math], we know that [math]0 = \arctan 0[/math] and [math]\frac{\pi}{4} = \arctan 1[/math]. Hence

This is a fascinating result: The number [math]\pi[/math] is equal to four times the area bounded by the curve [math]y = \frac{1}{1 + x^2}[/math], the [math]x[/math]-axis, and the lines [math]x= 0[/math] and [math]x = 1[/math].

The function [math]\cot[/math] is strictly decreasing on the open interval [math](0, \pi)[/math]. With its domain restricted to this interval, [math]\cot[/math] therefore has an inverse function, which we denote [math]\cot^{-1}[/math] or [math]\mathrm{arccot}[/math]. The relation between the two functions [math]\mathrm{arccot}[/math] and [math]\arctan[/math] is the same as that between [math]\arccos[/math] and [math]\arcsin[/math],

The proof is analogous to the proof of (4.3) and is left to the reader as an exercise. It is a corollary that the derivative of [math]\mathrm{arccot}[/math] is the negative of the derivative of [math]\arctan[/math]. Hence

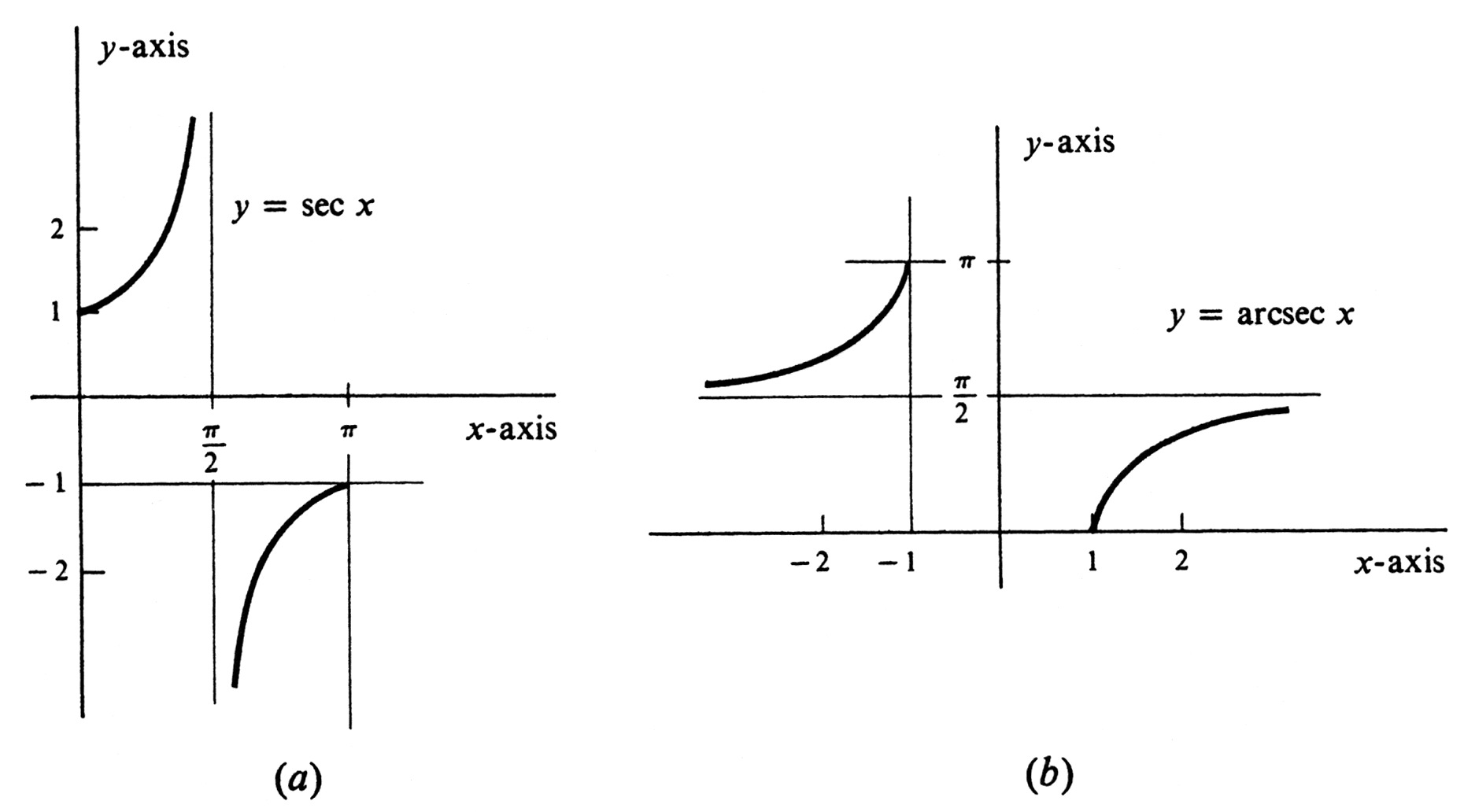

Here again, we see another indefinite integral of [math]\frac{1}{1 + x^2}[/math], the function [math]-\mathrm{arccot}\; x[/math]. The union of the two half-open intervals [math]\Bigl[0, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr)[/math] and [math](\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi][/math] consists of all real numbers [math]x[/math] such that [math]0 \leq x \leq \pi[/math] and [math]x \neq \frac{\pi}{2}[/math]. It can be seen from the graph of the equation [math]y = \sec x[/math] in Figure 13, page 308, that if [math]a[/math] and [math]b[/math] are two numbers in the union [math][0, \frac{\pi}{2}) \cup (\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi][/math] and if [math]a \neq b[/math], then [math]\sec a \neq \sec b[/math]. We omit [math]\frac{\pi}{2}[/math] because the secant of that number is not defined. It follows that the function [math]\sec[/math] with domain restricted to [math]\Bigl[0, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr) \cup \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi\Bigr][/math] has an inverse, which is denoted [math]\sec^{-1}[/math] or [math]\mathrm{arcsec}[/math]. Thus

The graph of the function [math]\mathrm{arcsec}[/math] is shown in Figure 18(b). Its range is the union [math]\Bigl[0,\frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr) \cup \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi \Bigr][/math]. As can be seen from Figure 18(a), the function sec maps the set [math]\Bigl[0, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr) \cup \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi \Bigr][/math] onto the set of all real numbers with absolute value greater than or equal to 1. Hence the domain of $\mathrm{arcsec}$ is the set of all real numbers $x$ such that $|x| \geq 1$.

The derivative can again be found by implicit differentiation. Let [math]y = \mathrm{arcsec}\; x[/math]. Then [math]x = \sec y[/math] and

Thus

Using the identity [math]\sec^{2} y = 1 + \tan^{2} y[/math] and the equation [math]x = \sec y[/math], we obtain

If [math]x \geq 1[/math], then [math]0 \leq y \lt \frac{\pi}{2}[/math], and so [math]\sec y \tan y[/math] is nonnegative. Hence

On the other hand, if [math]x \leq -1[/math], then [math]\frac{\pi}{2} \lt y \leq \pi[/math], and in this case both [math]\sec y[/math] and [math]\tan y[/math] are nonpositive. Their product is therefore again nonnegative; i.e.,

It follows that both cases are covered by the single equation [math]\sec y \tan y = |x| \sqrt{x^{2} -1}[/math]. Hence [math]\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{1}{|x| \sqrt{x^2 - 1}}[/math], and we have derived the formula

The final inverse trigonometric function is the inverse of the cosecant with domain restricted to the union [math]\Bigl[ -\frac{\pi}{2}, 0\Bigr) \cup \Bigl(0, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr][/math]. This function, denoted [math]\csc^{-1}[/math] or [math]\mathrm{arccsc}[/math], has range equal to [math]\Bigl[ - \frac{\pi}{2}, 0\Bigr) \cup \Bigl(0, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr][/math] and domain equal to the set of all real numbers [math]x[/math] such that [math]|x| \geq 1[/math]. The analogue of (4.3) and (4.7) is valid. That is,

The proof mimics that of (4.3). Let [math]y = -\frac{\pi}{2} - \mathrm{arccsc}\; x[/math]. Then [math]\mathrm{arccsc}\; x = \frac{\pi}{2} - y[/math], and so [math]x = \csc \Bigl(\frac{\pi}{2} - y \Bigr)[/math]. Thus

From this it follows at once that

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.