Trigonometric Substitutions

In this section we shall study a technique of integration which is particularly useful for finding integrals of functions of [math]\sqrt{a^2 - x^2}[/math], [math]\sqrt{a^2 + x^2}[/math], and [math]\sqrt{x^2 - a^2}[/math]. The technique is that of trigonometric substitutions and is based on some of the elementary trigonometric identities developed in Chapter 6. We shall develop the method by doing specific examples.

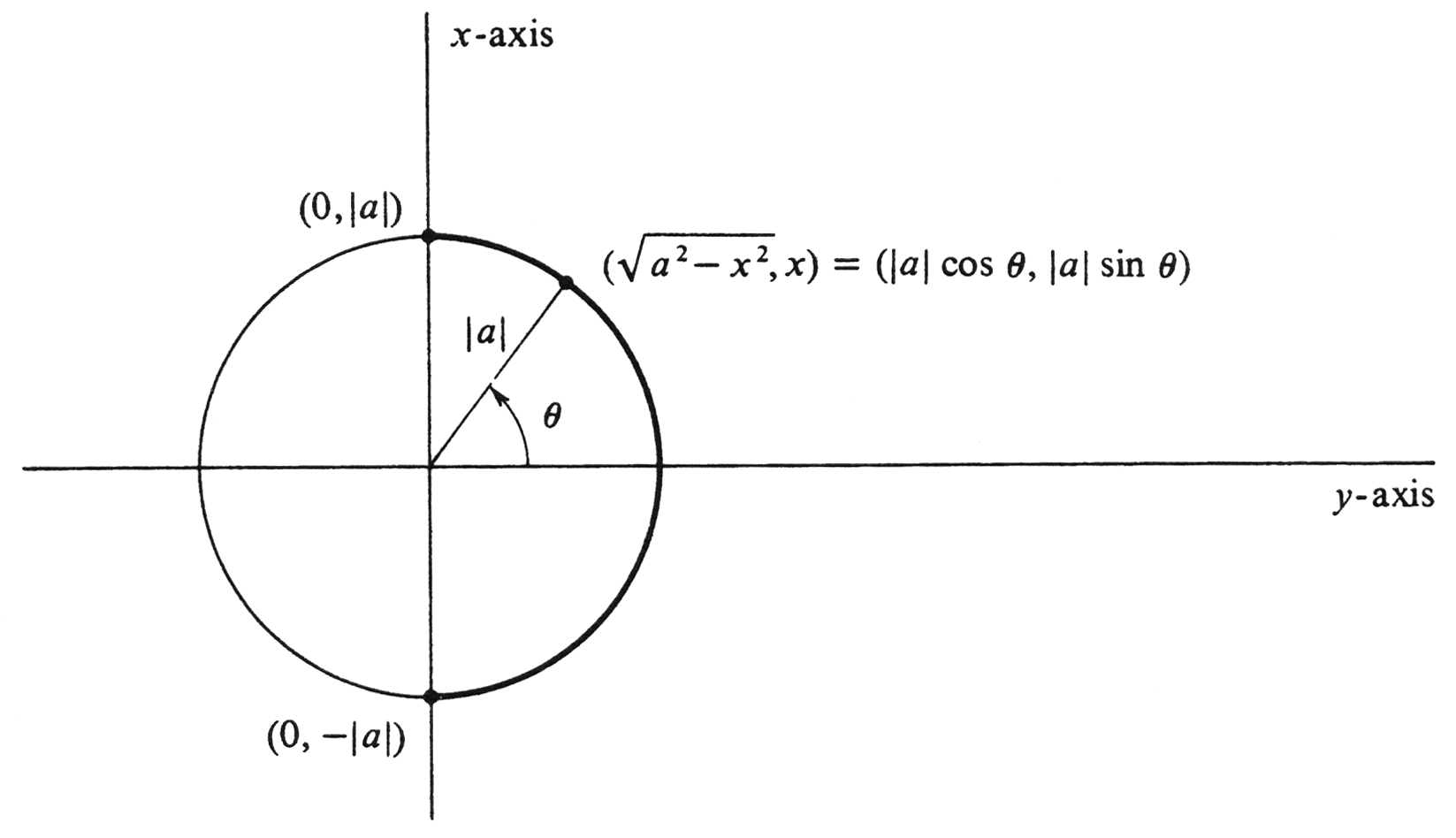

Consider the problem of evaluating [math]\int \sqrt{a^2 - x^2}dx[/math]. The domain of the function [math]\sqrt{a^2 - x^2}[/math] is the closed interval [math][-|a|, |a|][/math]. In what follows it will be convenient to view this interval as lying on the vertical axis, and, for this reason, the traditional positions of the [math]x[/math]-axis and the [math]y[/math]-axis will be interchanged. For every real number [math]x[/math] in the domain [math][-|a|, |a|][/math], the point [math](\sqrt{a^2 - x^2}, x)[/math] lies on the semicircle in the right half-plane with radius lal and center at the origin (see Figure 1). It follows from the definition of the trigonometric functions sine and cosine on page 282 that this point [math](\sqrt{a^2 - x^2}, x)[/math] is equal to [math](|a| \cos \theta, |a| \sin \theta)[/math], where [math]\theta[/math] is the radian measure of the angle denoted by the same letter in Figure 1. Hence

We shall restrict [math]\theta[/math] to the interval [math]\Bigl[-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr][/math]. Then [math]\theta[/math] is uniquely defined by equations (1), and, as [math]\theta[/math] takes on all values in this interval, [math]x[/math] assumes all values in the domain of the function [math]\sqrt{a^2 - x^2}[/math]. Using equations (1), we obtain [math]dx = |a| \cos \theta d\theta[/math] and

Since [math]\cos^{2} \theta = \frac{1}{2}(\cos 2 \theta + 1)[/math],

But [math]\theta = \arcsin \frac{x}{|a|}[/math] and

Substituting back, we get

In general, with any integral involving [math]\sqrt{a^2 - x^2}[/math], we make the trigonometric substitutions based on equations (1); i.e., we replace [math]x[/math] by [math]|a| \sin \theta, \sqrt{a^2 - x^2}[/math], by [math]|a| cos \theta[/math], and [math]dx[/math] by [math]|a| \cos \theta d\theta[/math]. Note that there is an equivalent alternative procedure: We may set [math]x = |a| \cos \theta[/math] and restrict [math]\theta[/math] to the interval [math][0, \pi][/math]. Then [math]x[/math] can take on all values in the interval [math][-|a|, |a|][/math] as

before, and, in addition, [math]sin [/math] will be nonnegative. Since [math]\cos^{2}\theta + \sin^{2}\theta = 1[/math], we will have

Thus the integral may be evaluated equally well using the equations

Of course, if these substitutions are used, then [math]dx = - |a| \sin \theta d\theta[/math]. Geometrically, equations (2) are obtained by starting from the point [math](x, \sqrt{a^2 - x^2})[/math], which lies on the semicircle in the upper half-plane instead of the right half-plane. A definite integral may be simpler to evaluate than an indefinite integral, since we may use the Change of Variable Theorem for Definite Integrals (see page 215) and thereby avoid the substitution back to the original variable.

Example

Evaluate the definite integral

Using equations (1), we define [math]\theta[/math] by setting [math]x = 4 \sin \theta[/math] and [math]\sqrt{a^{2} - x^{2}} = 4 \cos \theta[/math]. It follows that [math]dx = 4 \cos \theta d\theta[/math]. If [math]x = 2[/math], then [math]\sin \theta = \frac{1}{2}[/math] and so [math]\theta = \frac{\pi}{6}[/math]. If [math]x = 2\sqrt3[/math], then [math]\sin \theta = \frac{\sqrt3}{2}[/math] and [math]\theta = \frac{\pi}{3}[/math]. Hence

Since [math]\sin^{2} \theta = \frac{1}{2}(1 - \cos 2\theta)[/math], we obtain

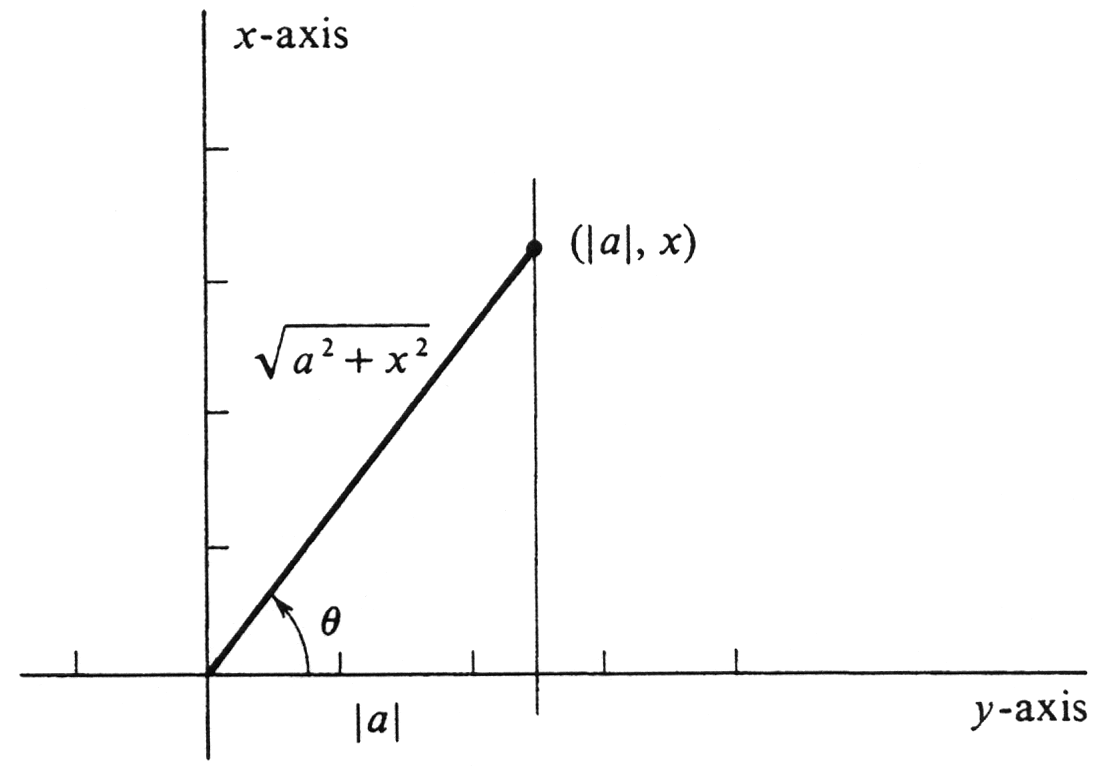

Next we consider integrals involving [math]\sqrt{a^2 + x^2}[/math]. The domain of the function [math]\sqrt{a^2 + x^2}[/math] is the set of all real numbers, i.e., the unbounded interval [math](-\infty, \infty)[/math]. Geometrically, we shall again find it convenient to place this domain on the vertical axis and to interchange the usual [math]x[/math]-axis and [math]y[/math]-axis in the picture. For every real number [math]x[/math], consider the point [math](|a|, x)[/math], and let [math]\theta[/math] be the radian measure of the angle shown in Figure 2. It follows that

We restrict [math]\theta[/math] to the open interval [math]\Bigl(-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \Bigr)[/math]. In this way, [math]\theta[/math] is uniquely determined by [math]x[/math] according to equations (3), and the interval [math](-\infty, \infty)[/math] of all possible values of [math]x[/math] corresponds in a one-to-one fashion to the interval [math]\Bigl(-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2} \Bigr)[/math] of all values of [math]\theta[/math]. It follows from the equation [math]x = |a| \tan \theta[/math] that [math]dx = |a| \sec^{2} \theta d\theta[/math]. Hence, if we substitute [math]|a| \tan \theta[/math] for [math]x[/math], we substitute [math]|a| \sec \theta[/math] for [math]\sqrt{a^2 + x^2}[/math] and [math]|a| \sec^{2}\theta d\theta[/math] for [math]dx[/math]. Algebraically, the substitutions given by equations (3) arise from the trigonometric identity [math]1 + \tan^{2} \theta = \sec^{2}\theta[/math]. If we set [math]x = |a| \tan \theta[/math], then [math]x[/math] will assume all real values as [math]\theta[/math] takes on all values in the open interval [math]\Bigl(-\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr)[/math]. Moreover, [math]\sec \theta[/math] is positive in this interval. It follows that

Example

Integrate [math]\int \frac{dx}{\sqrt{a^2 + x^2}}[/math] . Letting [math]x = |a| \tan \theta[/math], we obtain [math]\sqrt{a^2 + x^2}= |a| \sec \theta[/math] and [math]dx = |a| \sec^{2}\theta d\theta[/math]. Henee

It was shown in Section 2 that

Consequently,

Using the properties of the logarithm, we may write

Since [math]-\ln|a|+ c[/math] is no more or less arbitrary as a constant than [math]c[/math] itself, we conclude that

By trigonometric substitutions, functions of [math]\sqrt{x^2 -a^2}[/math] may frequently be put in a form so that integration is possible. Since [math]\sqrt{x^2 - a^2}[/math] is defined if and only if [math]|x| \geq |a|[/math], the domain of the function [math]\sqrt{x^2 - a^2}[/math], unlike the others, is the union of two intervals: [math](-\infty, -|a|][/math] and [math][|a|, \infty)[/math]. In this ease we shall set [math]x = |a| \sec \theta[/math]. Using the identity [math]1 + \tan^{2}\theta = \sec^{2} \theta[/math], we obtain

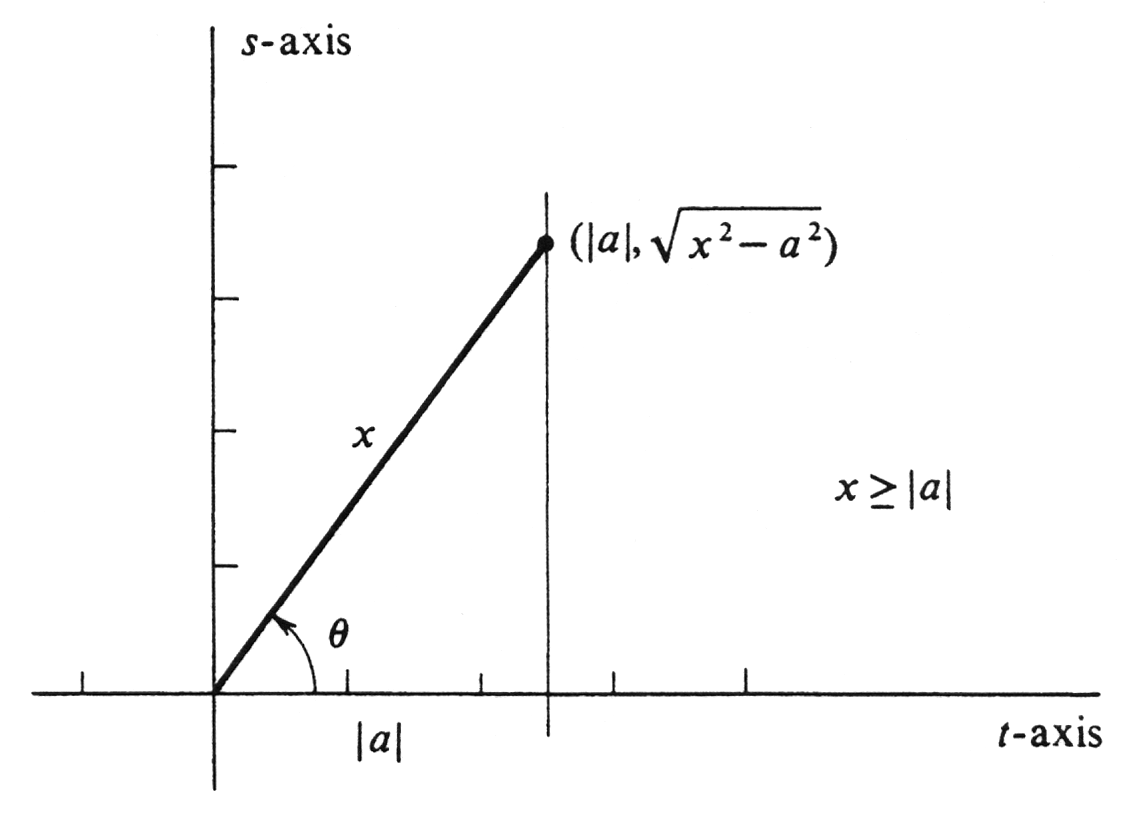

If [math]\theta[/math] is restricted to the interval [math]\Bigl[0, \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr)[/math], then [math]\tan \theta[/math] is nonnegative, and, as [math]\theta[/math] takes on all values in this interval, [math]x[/math] assumes all values in [math][|a|, \infty)[/math]. Similarly, if [math]\theta[/math] is restricted to the interval [math]\Bigl[-\pi, -\frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr)[/math] then [math]\tan \theta[/math] is again nonnegative, and, as [math]\theta[/math] runs through this interval, [math]x[/math] correspondingly traverses [math](-\infty,-|a|][/math] (in the opposite direction). Thus we have defined a new variable [math]\theta[/math] by the equations

These equations can also be obtained geometrically. Figure 3 illustrates the situation for [math]x \geq |a|[/math]. For every such [math]x[/math], consider the point [math](|a|, \sqrt{x^2 - a^2})[/math] in the plane, and let [math]\theta[/math] be the radian measure of the angle shown. Since [math]x[/math] appears only as the hypotenuse of a right triangle, we have used letters other than [math]x[/math] and [math]y[/math] in labeling the horizontal and vertical axes.

It follows from [math]x = |a| \sec \theta[/math] that [math]dx = |a| \sec \theta \tan \theta d\theta[/math]. Hence if we make the trigonometric substitutions based on equations (4), we substitute [math]|a| \sec \theta \tan \theta d\theta[/math] for [math]dx[/math].

Example

Find the indefinite integral

and evaluate the definite integral

For part (a), we let [math]x = |a| \sec \theta[/math] and [math]\sqrt{x^2 - a^2} = |a| \tan \theta[/math]. Then [math]dx = |a| \sec \theta \tan\theta d\theta[/math] and

It was shown in Section 2 that

Hence

But [math]\sec \theta = \frac{x}{|a|}[/math] and [math]\tan \theta = \frac{\sqrt{x^2 - a^2}}{|a|}[/math] and, substituting back, we therefore obtain

Since [math]\ln \Big| \frac{x}{|a|} + \frac{\sqrt{x^2 - a^2}}{|a|} \Big| = \ln | x + \sqrt{a^2 - x^2} | - \ln |a|[/math] and since [math]c[/math] is an arbitrary constant, we may incorporate the term [math]-\ln |a|[/math] into the constant of integration and conclude that

For the definite integral in part (b), we introduce [math]\theta[/math] as the variable of integration by letting [math]x = 3 \sec \theta[/math]. Then [math]\sqrt{x^2 - 9} = 3 \tan \theta[/math] and [math]dx = 3 \sec \theta \tan \theta d\theta[/math]. Restricting [math]\theta[/math] to the interval [math]\Bigl[-\pi, - \frac{\pi}{2}\Bigr )[/math] we see that, when [math]x = - 6[/math], [math]\sec \theta = - 2[/math] and so [math]\theta = - \frac{2\pi}{3}[/math]. Similarly, when [math]x = - 3\sqrt 2[/math], [math]\sec \theta = -\sqrt 2[/math] and [math]\theta = - \frac{3\pi}{4}[/math]. With these substitutions and the Change of Variable Theorem for Definite Integrals, we obtain

To integrate this, we replace a factor of [math]\sec^{2}\theta [/math]in the integrand by [math]1 + \tan^{2} \theta[/math]. The integral then becomes

Since [math]d \tan \theta = \sec^{2}\theta d\theta[/math], it is easy to find antiderivatives of [math]\tan^{2}\theta \sec^{2} \theta[/math] and [math]\tan^{4}\theta \sec^{2}\theta[/math]. Hence

and the example is finished.

Although the trigonometric substitutions developed in this section have been primarily directed at integrands containing certain square roots, we can equally well apply them to other functions of [math]a^2 - x^2[/math], [math]a^2 + x^2[/math], and [math]x^2 - a^2[/math]. For example, if we let [math]x = |a| \tan \theta[/math], then [math]a^2 + x^2 = a^{2}(1 + \tan^{2}\theta) = a^{2} \sec^{2} \theta[/math] and [math]dx = |a| \sec^{2}\theta d\theta[/math]. We then obtain

Given a choice, one would probably not evaluate [math]\int \frac{dx}{a^2 + x^2}[/math] by this method. It is more likely that one would do the problem directly, remembering the formula [math]\int \frac{dx}{1 + x^2} = \arctan x + c[/math].

We conclude this section with consideration of the integral

where [math]n[/math] is any positive integer and the polynomial [math]ax^2 + bx + c[/math] is irreducible over the real numbers. To say that a quadratic polynomial is irreducible means that it cannot be written as the product of two linear factors. It follows from the familiar quadratic formula that [math]ax^2 + bx + c[/math] is irreducible over the real numbers if and only if [math]b^2 - 4ac \lt 0[/math]. We shall show, by means of the trigonometric substitution used in the preceding paragraph, that the integral (5) can be changed to

where [math]K[/math] is a constant. This latter integral, as we saw in Section 2, can always be integrated, and this means that it is always possible to integrate (5). This fact, which is of interest in itself, will play a part in a more general theory to be developed in Section 4. By first factoring and then completing the square, we obtain

Note that, since [math]b^2 - 4ac \lt 0[/math], we know both that [math]a \neq 0[/math] and that [math]\sqrt{4ac - b^2}[/math] is real. For convenience, we shall let [math]y = x +\frac{b}{2a}[/math] and [math]k = \frac{\sqrt{4ac - b^2}}{2a}[/math]. Then

and [math]dy = dx[/math]. Making the trigonometric substitution [math]y = |k| \tan \theta[/math], we have

and [math]dx = dy = |k| \sec^{2}\theta d\theta[/math]. It therefore follows that

where [math]k = \frac{|k|}{a^{n} k^{2n}}[/math]. Thus, every integral (5) can be integrated by first changing it into the integral of a power of a cosine by trigonometric substitutions and then by reducing the power of the cosine with the reduction formula on page 359.

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2008). "Crowell and Slesnick's Calculus with Analytic Geometry" (PDF). Retrieved Oct 29, 2024.