guide:C631488f9a: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

\newcommand{\NA}{{\rm NA}} | \newcommand{\NA}{{\rm NA}} | ||

\newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb}</math></div> | \newcommand{\mathds}{\mathbb}</math></div> | ||

The usefulness of the expected value as a prediction for the outcome of an experiment | The usefulness of the expected value as a prediction for the outcome of an experiment | ||

is increased when the outcome is not likely to deviate too much from the expected | is increased when the outcome is not likely to deviate too much from the expected | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

===Variance=== | ===Variance=== | ||

{{defncard|label=|id=def 6.4| Let <math>X</math> be a numerically valued random variable | {{defncard|label=|id=def 6.4|Let <math>X</math> be a numerically valued random variable | ||

with expected value <math>\mu = E(X)</math>. Then the ''variance'' of <math>X</math>, denoted by | with expected value <math>\mu = E(X)</math>. Then the ''variance'' of <math>X</math>, denoted by | ||

<math>V(X)</math>, is | <math>V(X)</math>, is | ||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

<span id="exam 6.13"/> | <span id="exam 6.13"/> | ||

'''Example''' | '''Example''' Consider one roll of a die. Let <math>X</math> be the number | ||

that turns up. To find | that turns up. To find | ||

<math>V(X)</math>, we must first find the expected value of <math>X</math>. This is | <math>V(X)</math>, we must first find the expected value of <math>X</math>. This is | ||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

\end{eqnarray*} | \end{eqnarray*} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

To find the variance of <math>X</math>, we form the new random variable <math>(X - \mu)^2</math> and | To find the variance of <math>X</math>, we form the new random variable <math>(X - \mu)^2</math> and | ||

compute its expectation. We can easily do this using the following table. | compute its expectation. We can easily do this using the following table. | ||

<span id="table 6.6"/> | <span id="table 6.6"/> | ||

{|class="table" | {|class="table" | ||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

||||| | ||||| | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |<math>x</math> || <math>m(x)</math> || <math>(x - 7/2)^2</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

|1 || 1/6 || 25/4 | |1 || 1/6 || 25/4 | ||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

|6 || 1/6 || 25/4 | |6 || 1/6 || 25/4 | ||

|} | |} | ||

From this table we find <math>E((X - \mu)^2)</math> is | From this table we find <math>E((X - \mu)^2)</math> is | ||

| Line 88: | Line 89: | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

V(X) = E(X^2) - \mu^2\ . | V(X) = E(X^2) - \mu^2\ . | ||

</math> | </math>|We have | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

| Line 131: | Line 132: | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

V(X + c) = V(X)\ . | V(X + c) = V(X)\ . | ||

</math> | </math>|Let <math>\mu = E(X)</math>. Then <math>E(cX) = c\mu</math>, and | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

| Line 158: | Line 159: | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

V(X + Y) = V(X) + V(Y)\ . | V(X + Y) = V(X) + V(Y)\ . | ||

</math> | </math>|Let <math>E(X) = a</math> and <math>E(Y) = b</math>. Then | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

| Line 195: | Line 196: | ||

\sigma(A_n) &=& \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt n}\ . | \sigma(A_n) &=& \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt n}\ . | ||

\end{eqnarray*} | \end{eqnarray*} | ||

</math> | </math>|Since all the random variables <math>X_j</math> have the same expected value, we have | ||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block"> | ||

| Line 235: | Line 236: | ||

something about the spread of the distribution around the mean, we see that for large | something about the spread of the distribution around the mean, we see that for large | ||

values of <math>n</math>, the value of <math>A_n</math> is usually very close to the mean of <math>A_n</math>, which | values of <math>n</math>, the value of <math>A_n</math> is usually very close to the mean of <math>A_n</math>, which | ||

equals <math>\mu</math>, as shown above. This statement is made precise in Chapter | equals <math>\mu</math>, as shown above. This statement is made precise in Chapter [[guide:1cf65e65b3|Law of Large Numbers]], | ||

where it is called the Law of Large Numbers. For example, let <math>X</math> represent the roll | where it is called the Law of Large Numbers. For example, let <math>X</math> represent the roll | ||

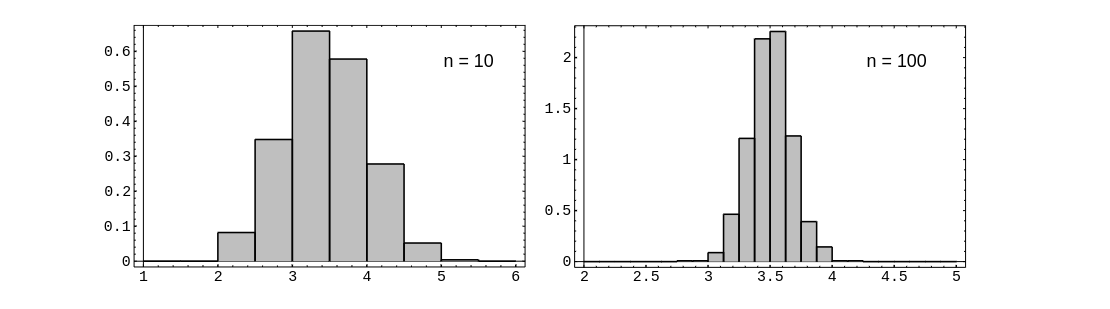

of a fair die. In | of a fair die. In [[#fig 6.4.5|Figure]], we show the distribution of a random variable | ||

<math>A_n</math> corresponding to <math>X</math>, for <math>n = 10</math> and <math>n = 100</math>. | <math>A_n</math> corresponding to <math>X</math>, for <math>n = 10</math> and <math>n = 100</math>. | ||

<div id=" | |||

[[File:guide_e6d15_PSfig6-4-5. | <div id="fig 6.4.5" class="d-flex justify-content-center"> | ||

[[File:guide_e6d15_PSfig6-4-5.png | 600px | thumb | Empirical distribution of <math>A_n</math>. ]] | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

<span id="exam 6.14"/> | <span id="exam 6.14"/> | ||

'''Example''' | '''Example''' | ||

<math>X_j</math> is the outcome if the | Consider <math>n</math> rolls of a die. We have seen that, if <math>X_j</math> is the outcome if the | ||

<math>j</math>th roll, then <math>E(X_j) = 7/2</math> and <math>V(X_j) = 35/12</math>. Thus, if <math>S_n</math> is the sum of | <math>j</math>th roll, then <math>E(X_j) = 7/2</math> and <math>V(X_j) = 35/12</math>. Thus, if <math>S_n</math> is the sum of | ||

the outcomes, and <math>A_n = S_n/n</math> is the average of the outcomes, we have | the outcomes, and <math>A_n = S_n/n</math> is the average of the outcomes, we have | ||

| Line 252: | Line 255: | ||

large <math>n</math>, we can expect the average to be very near the expected value. This is in | large <math>n</math>, we can expect the average to be very near the expected value. This is in | ||

fact the case, and we shall justify it in Chapter \ref{chp 8}. | fact the case, and we shall justify it in Chapter \ref{chp 8}. | ||

===Bernoulli Trials=== | ===Bernoulli Trials=== | ||

| Line 275: | Line 277: | ||

<math>p</math> and the variance tends to 0. This suggests that the frequency interpretation of | <math>p</math> and the variance tends to 0. This suggests that the frequency interpretation of | ||

probability is a correct one. We shall make this more precise in Chapter \ref{chp 8}. | probability is a correct one. We shall make this more precise in Chapter \ref{chp 8}. | ||

<span id="exam 6.15"/> | <span id="exam 6.15"/> | ||

'''Example''' | '''Example''' | ||

Let <math>T</math> denote the number of trials until the first | |||

success in a Bernoulli trials process. Then <math>T</math> is geometrically distributed. What | success in a Bernoulli trials process. Then <math>T</math> is geometrically distributed. What | ||

is the variance of <math>T</math>? In [[guide:448d2aa013#exam 5.7 |Example]], we saw that | is the variance of <math>T</math>? In [[guide:448d2aa013#exam 5.7 |Example]], we saw that | ||

| Line 340: | Line 344: | ||

the first six turns up is <math>(5/6)/(1/6)^2 = 30</math>. Note that, as <math>p</math> decreases, the | the first six turns up is <math>(5/6)/(1/6)^2 = 30</math>. Note that, as <math>p</math> decreases, the | ||

variance increases rapidly. This corresponds to the increased spread of the | variance increases rapidly. This corresponds to the increased spread of the | ||

geometric distribution as <math>p</math> decreases (noted in | geometric distribution as <math>p</math> decreases (noted in [[#fig 5.4|Figure]]). | ||

| Line 351: | Line 355: | ||

the value <math>\lambda</math>. In this case, <math>npq = \lambda q</math> approaches <math>\lambda</math>, since | the value <math>\lambda</math>. In this case, <math>npq = \lambda q</math> approaches <math>\lambda</math>, since | ||

<math>q</math> goes to 1. So, given a Poisson distribution with parameter <math>\lambda</math>, we should | <math>q</math> goes to 1. So, given a Poisson distribution with parameter <math>\lambda</math>, we should | ||

guess that its variance is <math>\lambda</math>. The reader is asked to show this in | guess that its variance is <math>\lambda</math>. The reader is asked to show this in [[exercise:497ffe72e6 |Exercise]]. | ||

==General references== | |||

{{cite web |url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~prob/prob/prob.pdf |title=Grinstead and Snell’s Introduction to Probability |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2006 |access-date=June 6, 2024}} | {{cite web |url=https://math.dartmouth.edu/~prob/prob/prob.pdf |title=Grinstead and Snell’s Introduction to Probability |last=Doyle |first=Peter G.|date=2006 |access-date=June 6, 2024}} | ||

Latest revision as of 01:48, 11 June 2024

The usefulness of the expected value as a prediction for the outcome of an experiment is increased when the outcome is not likely to deviate too much from the expected value. In this section we shall introduce a measure of this deviation, called the variance.

Variance

Let [math]X[/math] be a numerically valued random variable with expected value [math]\mu = E(X)[/math]. Then the variance of [math]X[/math], denoted by [math]V(X)[/math], is

Note that, by Theorem, [math]V(X)[/math] is given by

where [math]m[/math] is the distribution function of [math]X[/math].

Standard Deviation

The standard deviation of [math]X[/math], denoted by [math]D(X)[/math], is [math]D(X) = \sqrt {V(X)}[/math]. We often write [math]\sigma[/math] for [math]D(X)[/math] and [math]\sigma^2[/math] for [math]V(X)[/math].

Example Consider one roll of a die. Let [math]X[/math] be the number that turns up. To find [math]V(X)[/math], we must first find the expected value of [math]X[/math]. This is

To find the variance of [math]X[/math], we form the new random variable [math](X - \mu)^2[/math] and compute its expectation. We can easily do this using the following table.

| [math]x[/math] | [math]m(x)[/math] | [math](x - 7/2)^2[/math] |

| 1 | 1/6 | 25/4 |

| 2 | 1/6 | 9/4 |

| 3 | 1/6 | 1/4 |

| 4 | 1/6 | 1/4 |

| 5 | 1/6 | 9/4 |

| 6 | 1/6 | 25/4 |

From this table we find [math]E((X - \mu)^2)[/math] is

and the standard deviation [math]D(X) = \sqrt{35/12} \approx 1.707[/math].

Calculation of Variance

We next prove a theorem that gives us a useful alternative form for computing the variance.

If [math]X[/math] is any random variable with [math]E(X) = \mu[/math], then

We have

Using Theorem, we can compute the variance of the outcome of a roll of a die by first computing

and,

in agreement with the value obtained directly from the definition of [math]V(X)[/math].

Properties of Variance

The variance has properties very different from those of the expectation. If [math]c[/math] is any constant, [math]E(cX) = cE(X)[/math] and [math]E(X + c) = E(X) + c[/math]. These two statements imply that the expectation is a linear function. However, the variance is not linear, as seen in the next theorem.

If [math]X[/math] is any random variable and [math]c[/math] is any constant, then

Let [math]\mu = E(X)[/math]. Then [math]E(cX) = c\mu[/math], and

To prove the second assertion, we note that, to compute [math]V(X + c)[/math], we would replace

[math]x[/math] by [math]x + c[/math] and [math]\mu[/math] by [math]\mu + c[/math] in Equation. Then the

[math]c[/math]'s would cancel, leaving [math]V(X)[/math].

We turn now to some general properties of the variance. Recall that if [math]X[/math] and [math]Y[/math] are any two random variables, [math]E(X + Y) = E(X) + E(Y)[/math]. This is not always true for the case of the variance. For example, let [math]X[/math] be a random variable with [math]V(X) \ne 0[/math], and define [math]Y = -X[/math]. Then [math]V(X) = V(Y)[/math], so that [math]V(X) + V(Y) = 2V(X)[/math]. But [math]X + Y[/math] is always 0 and hence has variance 0. Thus [math]V(X + Y) \ne V(X) + V(Y)[/math].

In the important case of mutually independent random variables, however, the

variance of the sum is the sum of the variances.

Let [math]X[/math] and [math]Y[/math] be two independent random variables. Then

Let [math]E(X) = a[/math] and [math]E(Y) = b[/math]. Then

It is easy to extend this proof, by mathematical induction, to show that the variance of the sum of any number of mutually independent random variables is the sum of the individual variances. Thus we have the following theorem.

Let [math]X_1[/math], [math]X_2[/math], \dots, [math]X_n[/math] be an independent trials process with [math]E(X_j) = \mu[/math] and [math]V(X_j) = \sigma^2[/math]. Let

Since all the random variables [math]X_j[/math] have the same expected value, we have

We have seen that, if we multiply a random variable [math]X[/math] with mean [math]\mu[/math] and variance [math]\sigma^2[/math] by a constant [math]c[/math], the new random variable has expected value [math]c\mu[/math] and variance [math]c^2\sigma^2[/math]. Thus,

Finally, the standard deviation of [math]A_n[/math] is given by

The last equation in the above theorem implies that in an independent trials process, if the individual summands have finite variance, then the standard deviation of the average goes to 0 as [math]n \rightarrow \infty[/math]. Since the standard deviation tells us something about the spread of the distribution around the mean, we see that for large values of [math]n[/math], the value of [math]A_n[/math] is usually very close to the mean of [math]A_n[/math], which equals [math]\mu[/math], as shown above. This statement is made precise in Chapter Law of Large Numbers, where it is called the Law of Large Numbers. For example, let [math]X[/math] represent the roll of a fair die. In Figure, we show the distribution of a random variable [math]A_n[/math] corresponding to [math]X[/math], for [math]n = 10[/math] and [math]n = 100[/math].

Example Consider [math]n[/math] rolls of a die. We have seen that, if [math]X_j[/math] is the outcome if the [math]j[/math]th roll, then [math]E(X_j) = 7/2[/math] and [math]V(X_j) = 35/12[/math]. Thus, if [math]S_n[/math] is the sum of the outcomes, and [math]A_n = S_n/n[/math] is the average of the outcomes, we have [math]E(A_n) = 7/2[/math] and [math]V(A_n) = (35/12)/n[/math]. Therefore, as [math]n[/math] increases, the expected value of the average remains constant, but the variance tends to 0. If the variance is a measure of the expected deviation from the mean this would indicate that, for large [math]n[/math], we can expect the average to be very near the expected value. This is in fact the case, and we shall justify it in Chapter \ref{chp 8}.

Bernoulli Trials

Consider next the general Bernoulli trials process. As usual, we let [math]X_j = 1[/math] if the [math]j[/math]th outcome is a success and 0 if it is a failure. If [math]p[/math] is the probability of a success, and [math]q = 1 - p[/math], then

and

Thus, for Bernoulli trials, if [math]S_n = X_1 + X_2 +\cdots+ X_n[/math] is the number of successes, then [math]E(S_n) = np[/math], [math]V(S_n) = npq[/math], and [math]D(S_n) = \sqrt{npq}.[/math] If [math]A_n = S_n/n[/math] is the average number of successes, then [math]E(A_n) = p[/math], [math]V(A_n) = pq/n[/math], and [math]D(A_n) = \sqrt{pq/n}[/math]. We see that the expected proportion of successes remains [math]p[/math] and the variance tends to 0. This suggests that the frequency interpretation of probability is a correct one. We shall make this more precise in Chapter \ref{chp 8}.

Example Let [math]T[/math] denote the number of trials until the first success in a Bernoulli trials process. Then [math]T[/math] is geometrically distributed. What is the variance of [math]T[/math]? In Example, we saw that

In Example, we showed that

Thus,

so we need only find

To evaluate this sum, we start again with

Differentiating, we obtain

Multiplying by [math]x[/math],

Differentiating again gives

Thus,

and

For example, the variance for the number of tosses of a coin until the first head

turns up is [math](1/2)/(1/2)^2 = 2[/math]. The variance for the number of rolls of a die until

the first six turns up is [math](5/6)/(1/6)^2 = 30[/math]. Note that, as [math]p[/math] decreases, the

variance increases rapidly. This corresponds to the increased spread of the

geometric distribution as [math]p[/math] decreases (noted in Figure).

Poisson Distribution

Just as in the case of expected values, it is easy to guess the variance of the Poisson distribution with parameter [math]\lambda[/math]. We recall that the variance of a binomial distribution with parameters [math]n[/math] and [math]p[/math] equals [math]npq[/math]. We also recall that the Poisson distribution could be obtained as a limit of binomial distributions, if [math]n[/math] goes to [math]\infty[/math] and [math]p[/math] goes to 0 in such a way that their product is kept fixed at the value [math]\lambda[/math]. In this case, [math]npq = \lambda q[/math] approaches [math]\lambda[/math], since [math]q[/math] goes to 1. So, given a Poisson distribution with parameter [math]\lambda[/math], we should guess that its variance is [math]\lambda[/math]. The reader is asked to show this in Exercise.

General references

Doyle, Peter G. (2006). "Grinstead and Snell's Introduction to Probability" (PDF). Retrieved June 6, 2024.